Hitler's demise: 'The bloody dog is dead'

When reports emerged that the man responsible for one of the greatest tragedies the world has ever known was gone, the BBC turned to Shakespeare.

“The day is ours. The bloody dog is dead.”

That line from the final scene of Richard III led off the broadcaster’s initial commentary on the death of Adolf Hitler, and everything about it rang true.

By the time German radio announced late on May 1, 1945 that the Fuehrer was dead and Adm. Karl Dönitz had succeeded him as head of state, Russian troops had all but overrun Berlin. The war in Europe clearly was in its final moments, despite initial German insistence that the fight would continue.

The result, by then, was inevitable. And without the fanatical leadership of the tyrant who had led Germany — and the world — down this path, there was no question how it would end.

We now know that Hitler shot himself in the head at the Reich Chancellery around 3:30 p.m. on April 30, but the initial news of his demise was not so cut and dried.

Rumors had been swirling for days that Hitler was seriously ill, and perhaps had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. A report emerged from Stockholm that two Swedish diplomats who left Berlin at the end of April reported Hitler had been dead for two weeks.

Early on the evening of May 1, Hamburg radio told listeners to stand by for “a grave and important announcement for the German people.” Around 9:40 p.m., the station repeated that advisory and played excerpts of pieces from two of Hitler’s favorite composers: Wagner’s Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) and the Adagio from Anton Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony.

Finally, the station got to the point, as transcribed by the Associated Press: “At the fuehrer’s headquarters it is reported that our fuehrer, Adolf Hitler, has fallen this afternoon in his command post at the Reich Chancellery, fighting up to his last breath against Bolshevism.”

Then came the surprising news that Dönitz — not Heinrich Himmler, the universally anticipated successor — would take over as leader of Germany. Dönitz reiterated the news that Hitler was dead and pledged to continue the fight:

My first task will be to save the German people from the advance of the Bolshevist enemy. For this aim only the military struggle continues.

For as long and as far as the reaching of this aim will be impeded by the Anglo-Americans, we shall continue to defend ourselves against them and fight them.

The Anglo-Americans do not then continue the war for their own people, but solely for the spreading of Bolshevism in Europe. What the German people have achieved fighting this war and what they have suffered at the home front is a historic unicum.

Once Dönitz concluded his remarks, the station played Deutschland Uber Alles and the Horst Wessel Lied before lapsing into three minutes of silence. The broadcast was then repeated in English.

The BBC broke into regular programming shortly after the Hamburg broadcast, with announcer Stuart Hibberd repeating twice: “The German radio has just announced that Hitler is dead.”

Wire services flashed bulletins reporting on the broadcast, and full stories were available in plenty of time to be printed in evening editions across the United States and Canada on May 1.

While Hitler’s death undoubtedly was a critical milestone in a war that had raged for six years, most outlets absorbed the German radio announcement with a healthy skepticism, emphasizing the initial source of the report as inherently unreliable.

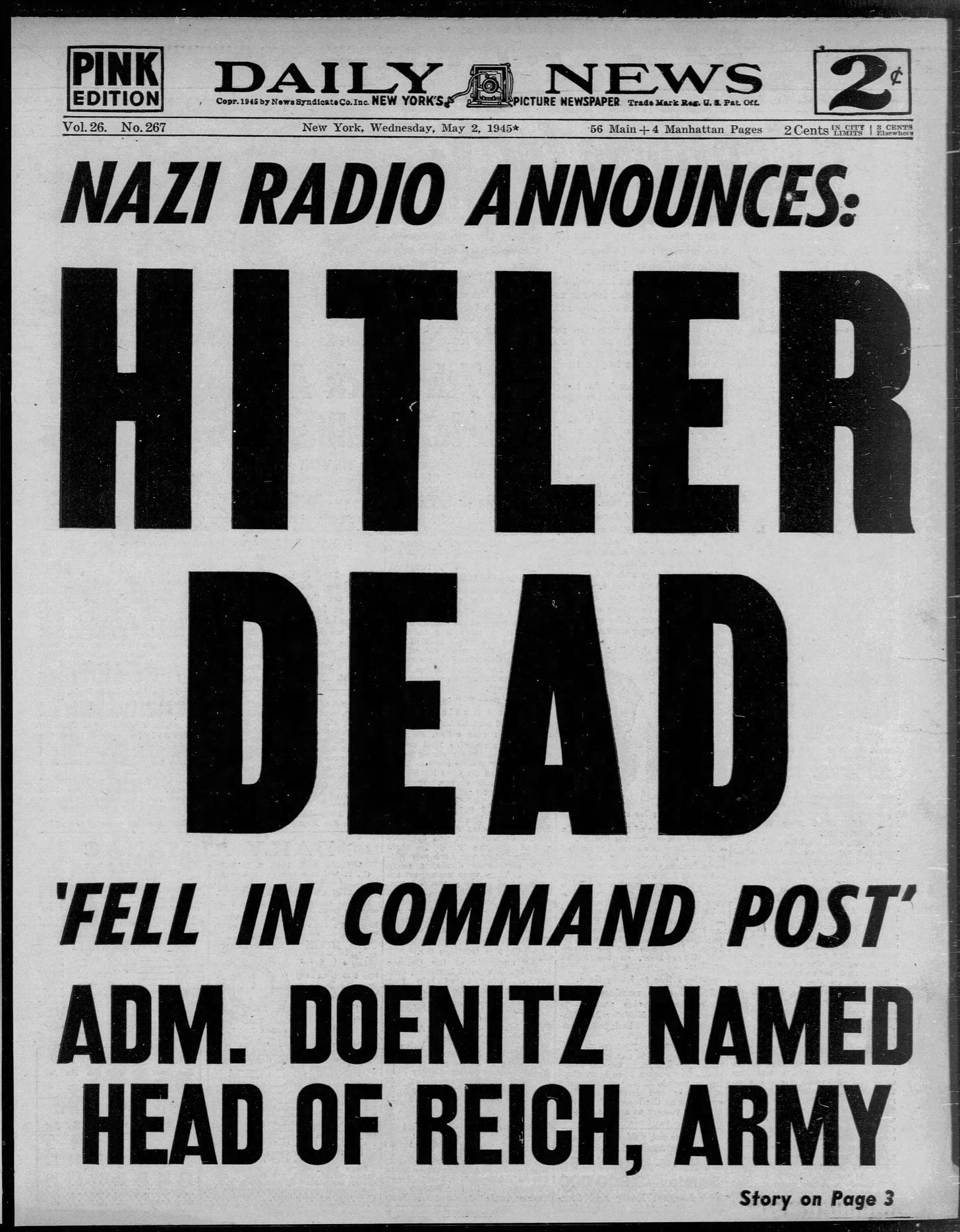

Many newspapers that had routinely trumpeted war developments with massive headlines took pains to qualify the news as unconfirmed, with even the New York Daily News adding a qualifying overline to its front-page “HITLER DEAD” headline.

Others ran with it full-bore, setting headlines in gigantic typefaces befitting the occasion.

Regardless of how aggressive editors were with their headlines, the accompanying stories in Allied newspapers were tempered with distrust of the messenger, and understandably so. But the story Sydney Gruson filed to The New York Times that evening from London hit it on the head:

Some doubted the truth of the announcement altogether, while others argued there would have been no sense of making it if it were not true, since Hitler was perhaps the last person around whom the Germans still in unconquered territory would rally.

But there was an almost complete lack of excitement here. Those who believed the report seemed to accept it as a matter of course that Hitler would die.

Still, there was plenty of skepticism about the veracity of the report.

The official response from Moscow said the Soviets would need to see a body to believe it. Louis P. Lochner, the longtime AP bureau chief in Berlin, wrote that evening that he found it “difficult to believe that Hitler is really dead or that he remained in Berlin during the Russian assault.”

Writing from Bavaria, Pierre J. Huss of the International News Service reported “seasoned Allied observers and even many Germans int he Munich area were frankly skeptical” about the announcement. Huss went on to suggest it was “not too melodramatic” to think that Hitler might undergo facial surgery and fingerprint alterations and revive the Nazi empire sometime down the road.

Reporting from Weimar, Germany, Harold Denny of The New York Times said prisoners at Buchenwald “generally discredited the report.”

“Hitler has been such a crook that some thought he was incapable of even dying honestly,” Denny wrote.

Stories filed from New York, London and elsewhere in Allied territory followed a similar theme, with the Times estimating eight of 10 rush-hour commuters believed the story was a Nazi ruse. And even those who believed it didn’t see much cause for celebration.

A mounted policeman on 42nd Street, “huddled glumly under his rubber cape,” told the Times: “It would have been good news twenty years ago. Late now.”

The following day, President Harry Truman sought to reassure the public that the news was true, saying at a press conference that he “had it on the best possible authority” that Hitler was dead, though he had no information on the specifics.

Confirmation, such as it was, came from the Soviets, who established control over Berlin the afternoon of May 2. They released a communique saying Hans Fritsche, a deputy to propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels captured by the Red Army, told them Hitler, Goebbels and army chief of staff Gen. Hans Krebs had killed themselves.

The Allies, of course, would never attain concrete confirmation of Hitler’s death, because his body was burned immediately after his suicide, but the world quickly moved on to the foremost priority on everyone’s mind: ending the fighting in Europe.

The Baltimore Sun wrote in a May 2 editorial: “Hitler is dead. There is a sigh of relief. But the sigh isn’t very satisfying. The war has not been waged to achieve the death of a single man. The stream of events flows on.”

Thankfully, Dönitz would not maintain the front of keeping up the fight for long. German forces in the Netherlands, Denmark and parts of northern Germany surrendered to Gen. Bernard Montgomery on May 4, German troops in Bavaria did the same on May 5, and the full capitulation came in Reims early on the morning of May 7.