An interview with Adolf Hitler

On June 14, 1940, the day German forces entered Paris to begin more than four years of occupation, an interview with the man responsible for that travesty appeared on dozens of front pages across the United States.

A few days earlier, as German forces raced across France, longtime Hearst Newspapers foreign correspondent Karl H. von Wiegand had been granted a rare audience with Adolf Hitler. He described their encounter in a large chateau that had been requisitioned as the headquarters for a German division commander: "With portraits of Belgian and French beauties of days that will never return looking down at us, we sat in the drawing room."

Looking back 80 years later, von Wiegand's interview is a remarkable document, difficult to wrap one's mind around given what would transpire over the next few years.

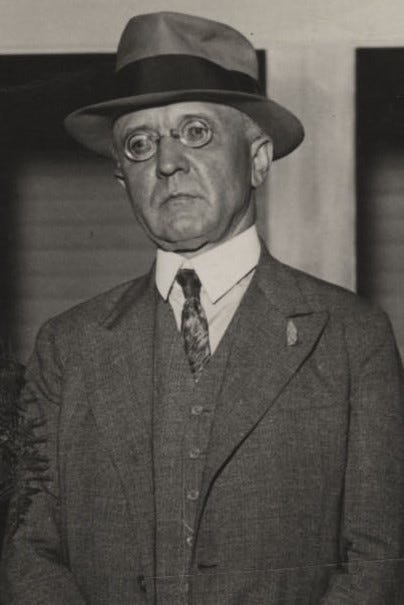

Von Wiegand, 65 years old at the time, had been born in Germany but moved to Iowa with his family as a child. He rose to fame as a foreign correspondent during the first World War, earning a reputation as someone who could be trusted to properly handle interviews with high-profile figures. He landed sitdowns with crown prince Wilhelm, Admiral von Tirpitz, Pope Benedict XV, and numerous other newsmakers.

He first met Hitler in 1921 and interviewed him in November 1922, famously describing him as the "German Mussolini."

The real German Fascisti are the national socialists and their Mussolini is Adolph Hitler, a man of the people, a private soldier during the war, a carpenter by trade, a magnetic speaker, having also exceptional organizing genius.

Aged 34, medium tall, wiry, slender, dark hair, cropped toothbrush mustache, eyes that spurt fire when in action, straight Grecian nose, finely chiseled features, with complexion so remarkably delicate that many a woman would be proud to possess it -- with all a bearing that creates an impression of dynamic energy well under control. ...

This is Hitler, who aspires to be Germany's Mussolini. He is one of the most interesting characters I have met in many months.

The two would meet again periodically over the years as Hitler consolidated his power. In an August 1932 piece, von Wiegand would write:

I have known Hitler for 10 or 11 years. I never had any difficulty in seeing him when I wanted to. On a number of occasions he has called on me to have a chat. We have lunched and dine together, especially in the early years of his tireless campaign to "save Germany." ...

In all these years and the hours we have talked I have not been able to come to a conclusion about Hitler that satisfied me that I was right. Each time I had to admit to myself that I did not know him.

These musings came after von Wiegand began the column by quoting an unnamed American magazine writer who had recently met Hitler for the first time appraising the Austrian's "startling insignificance." While von Wiegand could not quite get a feel for Hitler's full potential -- or the scope of his intentions -- he felt confident enough to disagree with his colleague's assessment.

Any man who can gather so many followers under his flag in a few years scarcely can be "insignificant."

By the time von Wiegand sat down with Hitler in June 1940, his instincts had been validated. While the world might not yet have grasped the full extent of Hitler's madness, he was without question a force to be reckoned with -- at least in Europe. And reinforcing that last bit was the reason von Wiegand had been summoned to the chateau.

The lengthy account he would file from France to Hearst Newspapers led with Hitler denying he had any designs on the United States, or the Americas in general. Surely cognizant of the dangers of the U.S. entering the war now that his armies had swept through the Low Countries and into Paris, he encouraged the Americans not to get involved in another European conflict, as they had in 1917-18:

"At no time has Germany had any territorial or political interest in the American Continent," Hitler declared.

Then, with rising voice: "Nor has Germany any such interest now. Whoever states anything to the contrary is lying deliberately for some purpose.

"How the American Continent shapes and leads its life is no concern of mine, and of no interest to Germany. And that, let me say, holds good not only for North America but equally so for South America."

From there, Hitler launched into his ultimate thesis, a reciprocal Monroe Doctrine of sorts that boiled down to this, in his words: "Therefore I say, America for Americans. Europe for Europeans."

After making clear the various reasons Americans shouldn't be concerned about his intentions, the conversation turned to enemies closer at hand. Hitler emphasized "again and again" that it was England that had declared war on Germany on "ridiculous, stupid pretexts" but denied any desire to break up the British Empire. Instead, he raged about not being permitted to build an empire of his own:

"I have asked nothing of England beyond that Germany should be considered and treated as an equal, that England would protect the German coast if Germany became involved in war and that I be given German colonies -- and I will get them!

"Openly it was declared and printed in London that national socialism must be destroyed, that Germany must be able to be broken up, utterly disarmed and made powerless. Never have I voiced any such aims or intentions against Britain.

"When battle after battle went against England, the rulers in London appealed to America with tears in their eyes, declaring Germany is menacing and seeking to break up the British Empire.

"One thing, it is true, is going to be destroyed. That is the capitalistic clique which was, and still is, prepared to sacrifice millions of human lives for their mean, petty, personal interests. And that, I am convinced, will not be done by me but by their own people."

Hitler's rhetoric against Britain and France continued on for hundreds of words. Near the end of the piece, von Wiegand asked Hitler to "give me an outline or some idea of his concept of the peace to come." The Führer "was disinclined to commit himself at this time," launching forth instead into a plea for "reason" on the behalf of his adversaries.

Jumping off from that point, von Wiegand's account concludes this way:

"If the military defeat of Great Britain and France should bring about a victory of reason, even in those countries, the sacrifices of this war will, perhaps for the future of the world, not have been so in vain as it may now seem."

As Hitler arose and shook hands with me, I asked him once more to spare Paris, if possible.

He replied: "You have that at heart no more than I have, and you will be no more happy than I will be if the French Army leaders show common sense and make that possible for me."