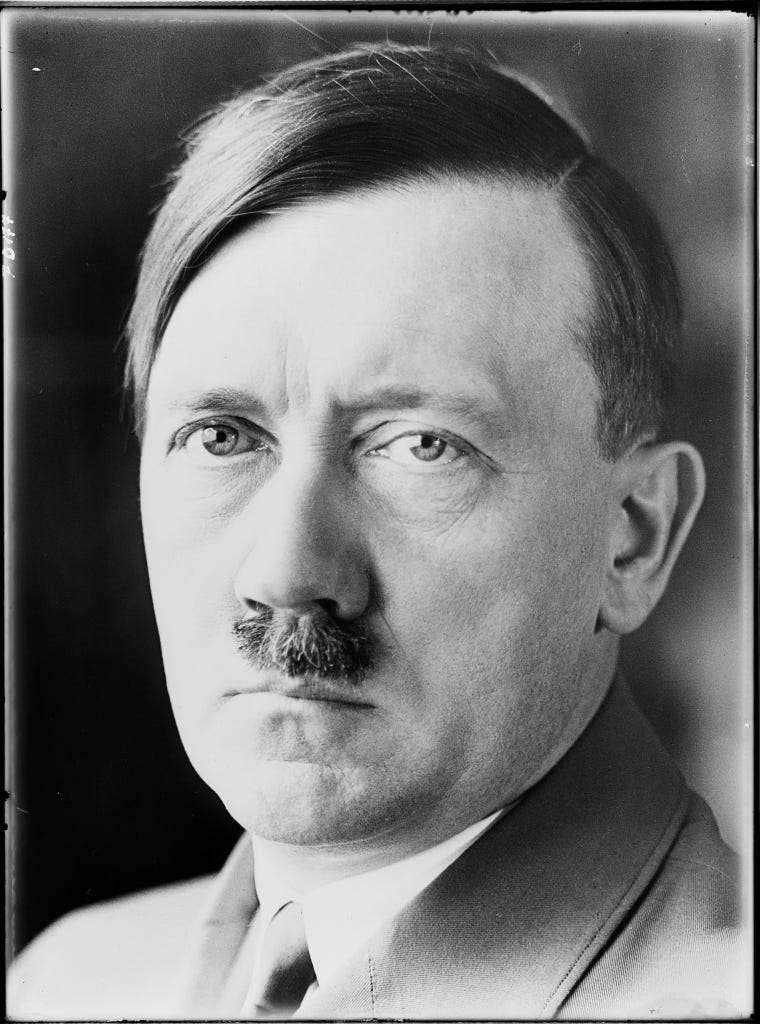

The July 20 plot on Hitler's life

At 12:30 p.m. local time on July 20, 1944, Adolf Hitler and about two dozen advisors and aides gathered for their daily military conference at the Wolfsschanze -- Wolf's Lair -- in East Prussia. Twelve minutes later, a bomb that had been placed in a briefcase under the conference table exploded, sparking chaos and uncertainty across the Third Reich.

The man who had planted the briefcase and left the building, Claus von Stauffenberg, was certain the blast had killed Hitler, and flew back to Berlin with the wheels of an attempted coup led by establishment military figures already in motion. But Hitler was not dead, and indeed within about 12 hours would be on the radio letting his subjects know he was still in charge.

That, as much as anything, explains why the world learned so much, so quickly about an event that in some circumstances might have been kept under wraps by any means necessary. Instead, the news of the attempt on Hitler's life made many evening newspapers in the United States that very day.

Initial reports came from the wire services, which pieced information together from German radio broadcasts. The Associated Press story written out of London began: "Berlin announced that Adolf Hitler was burned and bruised in an unsuccessful bombing attempt on his life today."

The broadcasts did not specify where the attack had occurred, but did insist Hitler was fine. After listing the various men in the room who had been injured and severely injured, DNB radio reported "The Fuehrer himself suffered no injuries apart from slight burns and contusions" and said he "resumed work at once," including a "lengthy conversation" with deposed Italian leader Benito Mussolini.

Grappling for answers, the AP cited a source saying the incident "probably" occurred at Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's headquarters in the Netherlands and speculating that internal Army disputes might have been at the root of the trouble. The story noted that only two weeks earlier, Field Marshal Günther von Kluge had replaced Gerd von Rundstedt as German commander in the west in a move with political undertones.

The story went on to quote one German radio announcer expressing on behalf of all citizens his "deep gratitude" for Hitler's survival and another suggesting "providence" had intervened -- a notion that would become a key touchstone for Nazi true believers once the extent of the plot became clear. The latter broadcast also intimated that the Allies might have been behind the attack.

The piece then listed the numerous known attempts on Hitler's life throughout the 1930s, the most recent of which had occurred nearly five years earlier, about two months after the invasion of Poland. But this incident stood apart, as Hitler himself soon made clear to his people.

Around 1 a.m. on July 21, Hitler addressed the nation on the radio, followed by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring and Adm. Karl Dönitz of the Navy. The Fuehrer got right to the point:

German men and women: I do not know how many times an attempt on my life has been planned and carried out. If I address you today I am doing so for two reasons: first, so that you shall hear my voice and know that I personally am unhurt and well and, second, so that you shall hear the details about a crime that has no equal in German history.

An extremely small clique of ambitious, unscrupulous and at the same time foolish, criminally stupid, officers hatched a plot to remove me and, together with me, virtually to exterminate the staff of the German High Command. The bomb that was placed by Col. Graf von Stauffenberg exploded two meters away from me on my right side. It wounded very seriously a number of my dear collaborators. One of them has died. I personally am entirely unhurt apart from negligible grazes, bruises or burns. This I consider to be confirmation of the task given to me by Providence to continue in pursuit of the aim of my life, as I have done hitherto.

In a broadcast that ran only six minutes, Hitler went on to rant against a small group of "usurpers" that tried to "thrust a dagger into our back as it did in 1918." He denied any significant rift with the army and said the attack was orchestrated by "a very small clique of criminal elements, which will now be exterminated quite mercilessly."

Hitler also announced that he had placed Heinrich Himmler in charge of army operations in Germany, further consolidating the SS chief's power, and vowed to "settle accounts in such a manner as we National Socialists are wont."

That process started within hours, as Himmler's men began arresting people believed to be even tangentially involved in the plot. They were too late to get their hands on the would-be assassin, however. Late on the 20th, shortly before Hitler addressed the nation, Gen. Friedrich Fromm had convened a summary court martial and convicted Stauffenberg and three other officers. The men were executed by a firing squad shortly after midnight.

That news also traveled quickly, with the Associated Press citing a German radio broadcast saying Stauffenberg and some other conspirators already had "been shot or have committed suicide." That announcement came around 3:20 a.m. local time, according to reports in British newspapers.

Several outlets reported telephone communication between Germany and the rest of the world had been halted on the evening of the 20th, but news began to trickle out as the bloody aftermath of the attempted coup unfolded.

The July 22 New York Times carried a story out of Stockholm reporting that "hundreds of officers, many of them highly placed," had been shot by Himmler's firing squads in Berlin. The story cited reports from passengers on a flight from Berlin to Stockholm, "which arrived here ten hours late because of Gestapo and Elite Guard action."

That purge, which ultimately would result in nearly 5,000 executions, spawned a series of analytical pieces that attempted to contextualize what might actually be happening behind the scenes as German hopes of victory faltered. Louis P. Lochner, the legendary AP Berlin bureau chief, led his analysis with a simple declarative:

Adolf Hitler's days are numbered. His purge of 1944 is something from which he, his party and his army will never recover. The purge of 1934 was child's play compared with it. This time the split goes through the entire nation. The alleged conspirators whose bomb barely missed the Fuehrer are but symbols of what millions of Germans are hoping and praying for. Disarmed, disfranchised, terrorized, they looked to the decent element in the army to do something to end Hitler's tyranny.

The conspirators chose the way of assassination. They failed this time. Hitler's life will be guarded more closely than ever. Many officers have been purged and will yet be purged. Hitler and Himmler always seize upon occasions of this kind to square accounts with everybody who ever dared cross their paths.

In Lochner's view, this evidence of significant internal rifts in Germany was evidence the "day of Allied victory" had drawn even closer. "When whole army divisions revolt at a critical moment," he concluded, "the twilight of the gods has begun."

Lochner wasn't wrong, though it took several more months and tens of thousands more lives lost throughout Europe to reach that denouement. But news of the plot did provide at least a temporary boost to Allied morale.

Traveling with the American First Army in Normandy, Mark S. Watson of the Baltimore Sun reported on July 21 "there was the liveliest interest today in the German announcement of the attempt on Hitler's life, followed by a further purge of German generals."

Reporting from Moscow, Alexander Kendrick of the Philadelphia Inquirer filed a story on the 22nd describing the Soviet view of the attack, which the official news agency Tass said must have been the work of a "widespread movement" against Hitler rather than just an isolated group of disaffected officers.

The Tass analysis ran on the foreign page in every Russian newspaper, Kendrick reported, taking up "one-twelfth of all available space" in the papers.

Tass' analysis of the German events, surveying all possible angles of the Hitler assassination plot, makes it clear that this is no Reichstag fire incident -- that is, provocation in anticipation of anti-Hitler activity -- but a fully realized attempt on the part of Junker officers to get rid of Hitler.

That was the takeaway most sources seemed to agree on in the days and hours following the July 20 attempt, though correspondents acknowledged at the time that they could not possibly have the whole story. Writing from Washington, Philip W. Whitcomb of the Baltimore Sun mused over the "startling possibilities and puzzling confusions" that surely were playing out behind the scenes in Germany.

"We may get the truth when the war is over," Whitcomb wrote. "At the end of the first 24 hours we have only a tangle of jigsaw pieces that may belong to several different pictures."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=88g88BObjJY