'We just walked': Anzio and the peril of first impressions

We’ve written more than once here about journalism being the first rough draft of history, the starting point in the written record of events that will be discussed and debated for decades or centuries to come. Of course, some drafts require more revision than others.

While it’s easy enough to look back from a distance of nearly 80 years and shake your head at some of the initial coverage of the landings at Anzio in the early morning hours of Jan. 22, 1944 given what we know now, the correspondents on the scene could only work with what they had in front of them. And from an Allied perspective, those early days looked like a rout.

The dateline from veteran Associated Press war correspondent Don Whitehead’s Jan. 23 dispatch read “AT THE FIFTH ARMY BEACHHEAD SOUTH OF ROME” and the story itself offered up a fourth-wall-breaking account of the Allies’ latest incursion into Europe.

The word “Anzio” does not appear in Whitehead’s lengthy account, nor in any of the other on-scene dispatches from the first couple of days. The key geographic marker in every report was Rome, a tantalizing 40 miles to the north. Based on the tone of those early dispatches, it would be easy for a reader to envision liberating armies marching into the Eternal City within a few weeks."

“For several hours we have been going around with our mouths open in amazement over the ease with which the army and navy managed to land troops behind the enemy lines,” Whitehead wrote. “I landed with the second assault wave at 2:10 a.m., but did not see a shot fired. We just walked. That’s how easy it was.”

Perhaps as a way to compensate for the relative lack of action he had to report, Whitehead spent the early part of his story illuminating the difficulties of getting his story off the beachhead: “After more than 24 hours ashore with the first assault troops to land behind the German lines, I have been able to get only 250 words of copy out by radio. Radios seem to have a peculiar way of losing all contact with the world during a time like this when you have a big story to tell.”

The business end of his story began like this:

Correspondents attached to the Fifth Army drew lots to see who would win a place with the amphibious force. There were seven places open. I was one of the lucky ones to win a spot and I was assigned to an advance unit, as was Homer Bigart of the New York Herald Tribune. Others were placed in various spots with various headquarters to spread the coverage over all units of the invading force.

We did not know when or where we were going, but we were told confidentially about the amphibious operation by which the Fifth Army hopes to smash into the enemy’s flank and thus open the road to Rome.

As I write this it appears that the planners of this operation conceived a brilliant one, for it has gone better than anyone could have dreamed.

His companion, Bigart, was similarly impressed:

On my beach not one soldier has fallen from German bullets. The few casualties were the result of mines and a few late morning air raids by half a dozen Focke-Wulfs. It is incredible.

For nearly three months the Germans have all but stalemated the Allies crossing through the mountains from Naples. And now the Allied Fifth Army, at a cost of a few dozen men, has landed on the front door step of Rome.

A British correspondent landing with his nation’s troops later in the morning termed it a “regatta” that “was more like a practice landing than a real operation.”

John Lardner of the North American Newspaper Alliance invoked similar imagery: “To the south of us, ships of all sizes stretch as far as the eye can see, a grand, secret, successful regatta of war from which the curtain of night has been been lifted.” Nearby, “as we awaited the landing, a brigadier and a colonel were arguing whether coffee or tea was best for breakfast.”

Reynolds Packard, the veteran United Press correspondent who had spent years reporting from Italy alongside his wife and fellow UP scribe Eleanor, noted that the Allies attained all of their first-day objectives for the invasion within four hours.

Landing ship tank men and officers seemed almost disappointed that they did not have a chance to run into any fighting.

“What a let down,” said Sgt. Oliver Atwood, New York City. “I was all set for some action.”

After wading ashore in cold, hip-deep water, Whitehead would spend a couple of hours hopping and jumping about in an effort to dry out and warm up his feet and legs, and “the sun felt good when it rose across the misty horizon.”

“Our men just kept marching straight to their objectives while armor, guns and ammunition poured ashore on a precision schedule,” Whitehead wrote, “and then we waited to see what the Germans would do about this threat to Rome and to their Cassino lines.”

That last line proved unfortunately prescient for those on the beachhead. As they waited, grateful to have made it ashore without a fight, German reinforcements rolled in around them. Though the defenders would not mount a significant counterattack for more than a week, tens of thousands of German troops poured into the area and ultimately left the landing forces trapped. So close to their ultimate objective in Italy on a map, but so far from achieving it they would hardly have believed it had you told them at the time how it would play out.

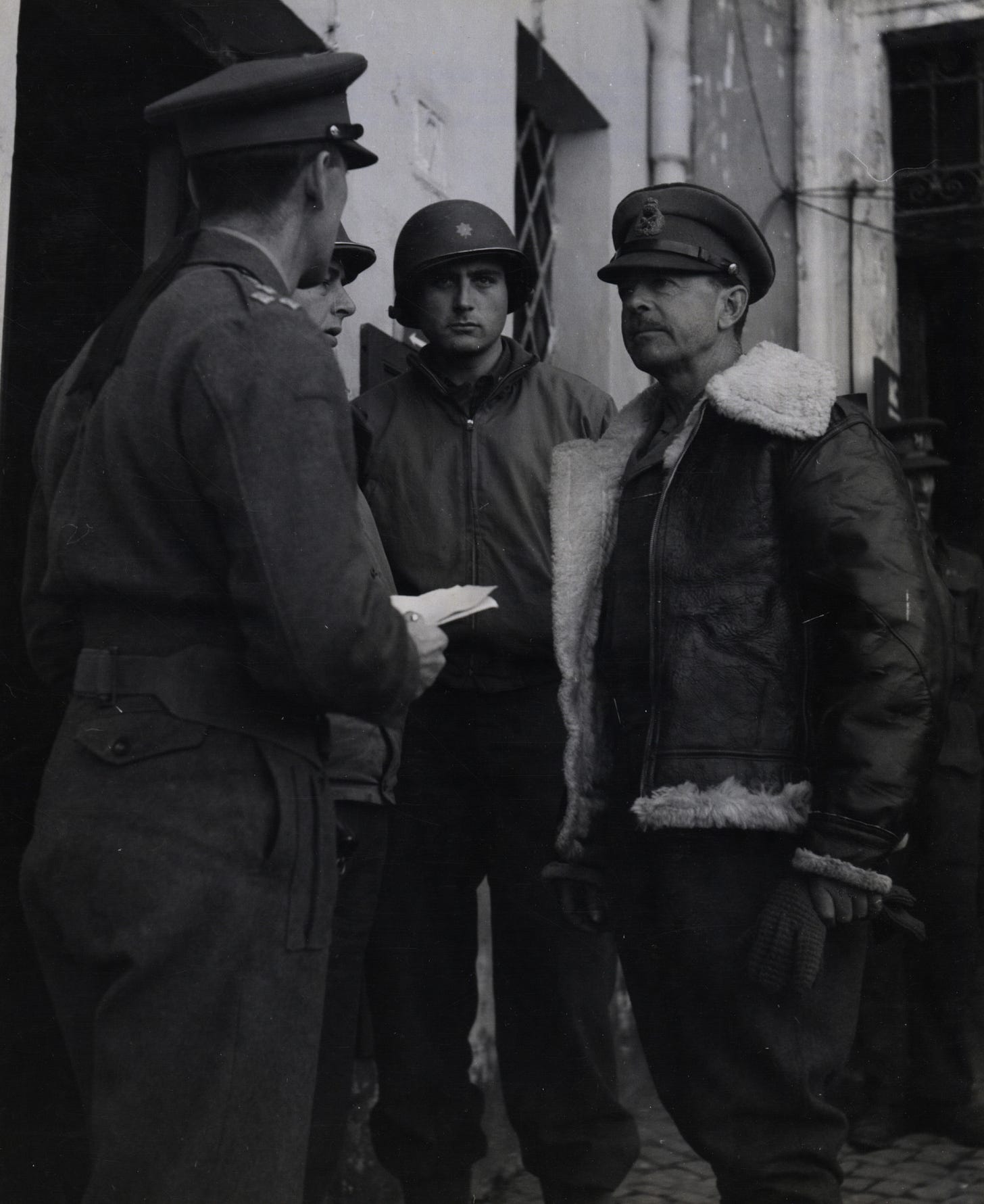

Operation Shingle, as the initial landings were known, soon devolved into a stalemate, and the Allied high command grew frustrated with the inaction of the commanding officer on the ground, American Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas. On Feb. 14, British Gen. Sir Harold Alexander, overall commander of Allied forces in Italy, visited the beachhead and encouraged Lucas to go on the offensive as soon as possible.

Frustrated as he may have been with Lucas’ inaction — the general would be relieved of his command eight days later — Alexander also made a point of chiding war correpondents for what he deemed excessively negative coverage of the operation. A British United Press report said Alexander banged his fist on a table as he insisted to the correspondents: “There is no Dunkirk here!”

He continued:

You are responsible people, and your work is vital because it is meant to give the people at home a true picture, but I received an urgent telegram that reports from the beachhead area are alarming the peopple. I beg you not to take that attitude. I am convinced that the Germans have lost the battle, even if things have not gone as fast as we would have liked.

The correspondents defended themselves, insisting that the stories they had filed were “objective and not alarmist,” but relations between the brass and the press continued to deteriorate as the stalemate unfolded. Correspondents bucked increasingly heavy-handed censorship at the beachhead that they complained had more to do with preserving morale than operational security.

The Daily Mail railed against increased restrictions in mid-February:

Such interference with the freedom of the press is unjustified on security grounds and therefore cannot be tolerated. Censorship for policy reasons is something news. A careful study of the psychological history of the Nettuno operation shows a sudden descent from optimism to pessimism, not incited by the journalists but by the highest official sources.

The piece went on to itemize the change in tone of statements of various high-ranking officials, from Alexander to Gen. Mark Clark, from the ease of the initial landings to the growing concerns about what the Allies might have gotten themselves into when they proved unable to break out from the beachhead.

As the weeks rolled on, many correspondents rotated out to cover the action elsewhere, whether inland in Italy or back to England to prepare for the increasingly inevitable landings in northwest Europe.

When the decisive breakout from Anzio finally came months later, Reynolds Packard filed his initial report from down the coast in Naples. “The Fifth Army forces in the long-dormant beachhead attacked the German perimeter Tuesday morning,” he wrote on May 23.

His UP colleague Robert Vermillion was on the scene:

Picked units of American shock troops rose from their slit trenches in broad daylight today and advanced across fields blood-red with poppies to break the German ring around the Anzio beachhead.

From an observation post on a slight rise I saw the infantrymen running and crawling across the flatland between our forward foxholes and the enemy — a field of waist-high weeds and poppies which had been nicknamed the “Bloody Mile.” …

The hands of my watch showed exactly 6:30 a.m. when officers bobbed up out of shallow trenches all along the front and beckoned the infantry to follow them. Soon streams of Americans could be seen working their way forward through smoke screens.

They bent low, seeking cover from the terrific German mortar and machine gun fire. But they kept inching forward.

This time, they kept going and were able to break through. Less than two weeks later, on June 4, Allied troops finally entered Rome.

MORE: Liberating the Eternal City

However symbolic that moment may have been, it was far from decisive — fighting in Italy would continue for nearly 11 more months. Not to mention the cost: The Allies suffered an estimated 4,400 combat deaths during the Anzio campaign, with 18,000 wounded and 6,800 missing or taken prisoner. According to a U.S. Army history, two-thirds of those losses were incurred within the first six weeks of the operation.

The same study notes that “the operation clearly failed in its immediate objectives of outflanking the Gustav Line, restoring mobility to the Italian campaign, and speeding the capture of Rome.”

While there were some benefits, most notably the need for the Germans to keep troops and equipment in the area when they could have been more effectively deployed elsewhere, history has not been kind to those who planned and led the Anzio campaign.

A dozen years after the breakout, in late May 1956, former President Harry Truman paid a visit to Salerno, site of the Allied landing in September 1943. As he surveyed the scene, Truman remarked to an Associated Press reporter, Fred J. Zusy, that the landings at Salerno and Anzio were “totally unnecessary and planned by some squirrel-headed general.”

“I don’t know who it was,” he continued. “There were a lot of easier places that could have been picked.”

The remarks ran in a short, unbylined story on the AP wire and immediately blew up. The following day, Truman’s secretary Eugene Bailey confronted Zusy, insisting: “That was not the president’s statement. He never told you that.” Zusy stuck to his guns, saying he had written down the quotes in his notebook as the pair were talking and they were “precisely as recorded.”

The controversy stirred longtime Baltimore Sun correspondent Price Day, who had covered the Italian campaign extensively — and even had a chance enounter with his little brother on the beachhead — to write a column musing on why Anzio remained such a flashpoint years after the fact. It concluded:

The truth is that Anzio was an error, and a bad one. Once the error had been made, anything that could be salvaged was all to the good. Something was salvaged. But the salvage was only salvage. It was not worth the cost. If it had been, those involved would not, twelve years afterward, be troubled about where the blame lies. Few such arguments arise in the wake of victories.

It doesn’t matter anymore, if it ever did. The controversy ought to come to an end. The dead of Anzio were not murdered by anybody. They were not victims, except as they were victims of war itself. Caught in one of war’s many misfortunes, they fought well and gallantly. The time has come to let them rest in peace.