Audie Murphy's Overlooked Heroics

Audie Murphy might be the most famous non-general from World War II -- or at least he was before "Band of Brothers" -- but most of the battlefield heroics that made him one of America's most decorated soldiers went unnoticed by the press until the final days of the war in Europe.

The diminutive Texan was just 16 years old when the U.S. entered the war, but he desperately wanted to join the cause. Born June 20, 1925, he couldn't bear the thought of waiting a year and a half to enlist, so his older sister Corinne signed off on a falsified birth year of 1924 that allowed him to enter the Army in June 1942, 10 days after he had actually turned 17. His enlistment papers put his vital stats at 5 feet, 5 1/2 inches and 112 pounds.

Despite his youth and size, Murphy quickly proved himself on the battlefield. He landed in Sicily with the 3rd Infantry Division in July 1943 and by December had been promoted to sergeant, then staff sergeant the following month.

He earned a Bronze Star in Italy in March 1944 for singlehandedly knocking out a German tank, and a Distinguished Service Cross in southern France in August for advancing on a group of about 20 Germans and killing six of them, wounding two, and taking 11 more prisoner. He added a Silver Star in October and was commissioned a second lieutenant later that month.

On and on it went, and it wasn't as if Murphy was going through all of this unscathed. He had been laid low by malaria in Italy, then wounded by mortar shrapnel and shot in the hip in a six-week span in the fall of 1944. Yet he kept on coming, returning to his unit as soon as he was healthy enough to fight.

With a record like that, there's little question Murphy carried the respect of his peers and superiors, but he had no public profile at this point. That wasn't unusual for an infantry grunt; Ernie Pyle couldn't get to everyone, and the correspondents in the theaters inevitably spent most of their time around headquarters. As such, Murphy's name doesn't surface in searches of newspapers available online at sites like Newspapers.com or the Texas Digital Newspaper Program.

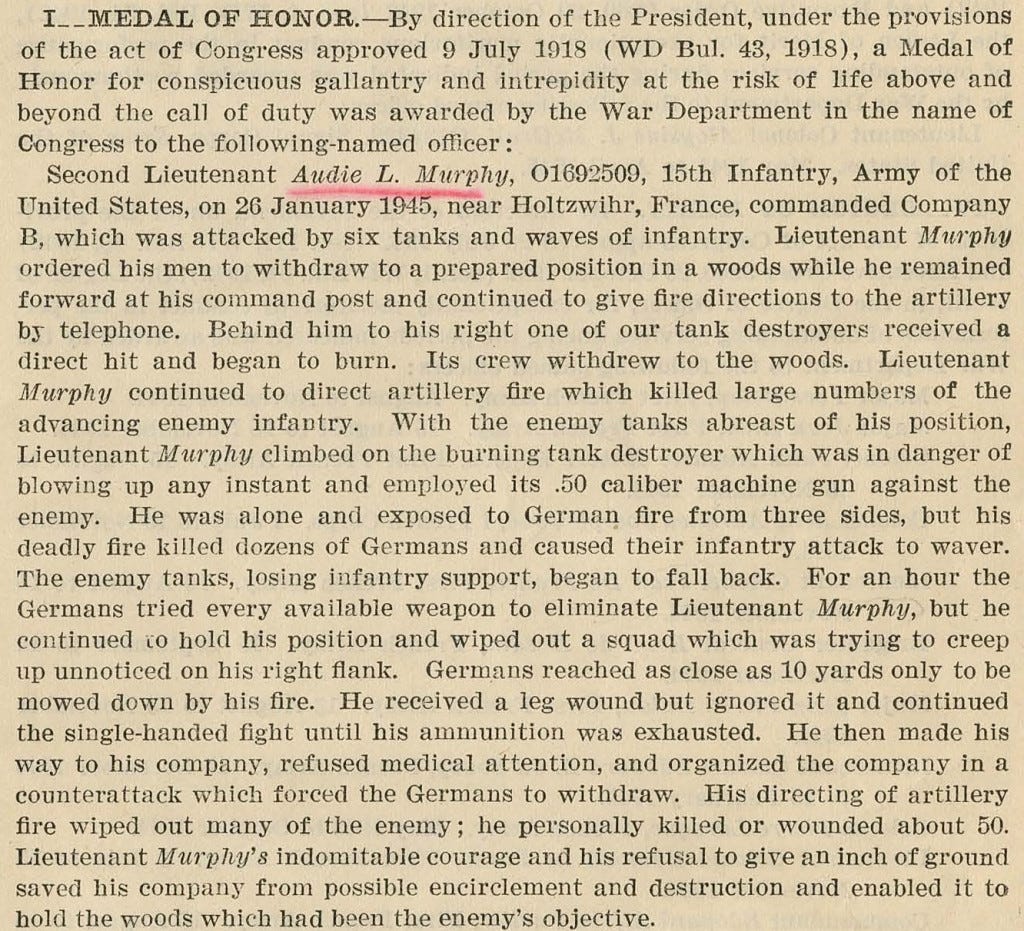

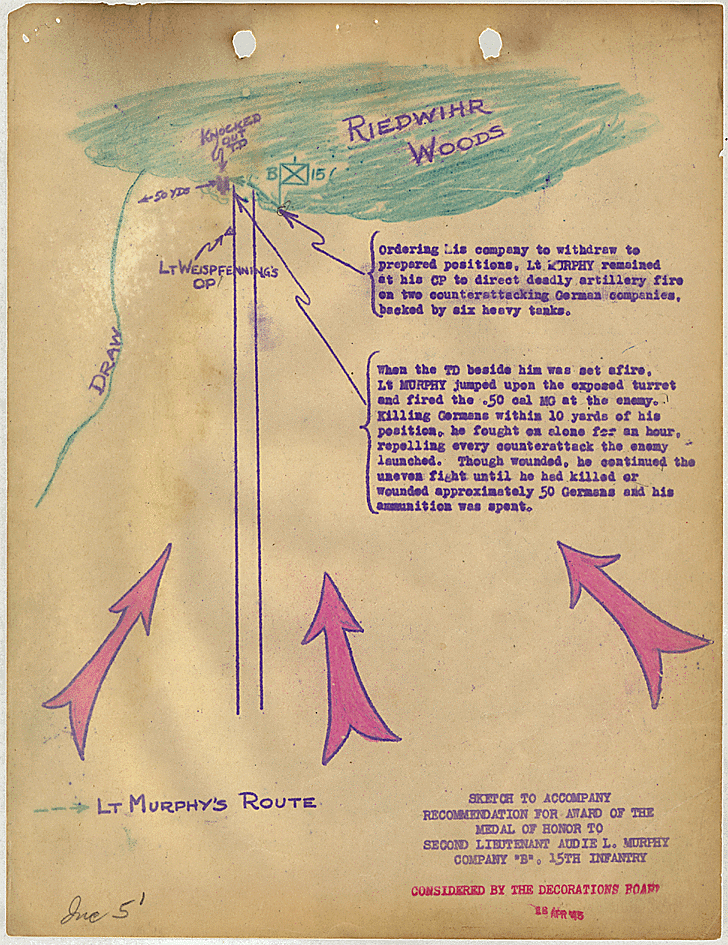

That would change after Murphy earned the Medal of Honor with his actions on January 26, 1945, as the 3rd Infantry attempted to reduce the Colmar Pocket in northeast France. Murphy's unit, Company B of the 15th Infantry Regiment, came under attack by six tanks and about 250 German infantrymen near Holtzwihr. His Medal of Honor citation tells the rest of the story:

Murphy was promoted to first lieutenant three weeks later and transferred to the 15th's headquarters, spelling the end of his duty at the sharp end after a remarkable journey across the battlefields of Europe.

The war in that theater ended with the German surrender on May 7, and two and a half weeks later, Murphy took the first step to becoming a household name. On May 24, 1945, the War Department announced he had been awarded the Medal of Honor. An Associated Press story introduced him to the nation, albeit with an incorrect age -- he was just 20 using the birth date on his Army paperwork, and 19 based on when he was actually born:

WASHINGTON, May 24 -- A young officer who manned a machine gun atop a blazing, abandoned tank destroyer and beat back a tank-led assault by 250 Germans will receive the nation's top decoration.

He is 1st Lt. Audie L. Murphy, 21, of Farmersville, Texas, who won the Congressional Medal of Honor near Holtzwihr, France, last Jan. 28. He was still a second lieutenant and new to the command of his company in the Third infantry division.

That day's Fort Worth Star-Telegram put the news on Page 1, with a bylined story from its Washington correspondent B.N. Timmons. A sidebar with a Farmersville dateline cited his sister, Corinne Burns, listing the medals Murphy already had been awarded before the highest honor.

From there, Murphy quickly became a media darling, at home in Texas and around the country. An AP story out of Austria the following day noted that Murphy had become the "second man in the Army to win every existing American medal for valor." The first was another 3rd Division soldier, Capt. Maurice "Footsie" Britt -- a former Arkansas standout who played for the Detroit Lions in 1941.

Yet another AP story followed from Salzburg on May 26, with Maj. Gen. John O'Daniel saying Murphy would get a hero's welcome at home after being granted a 30-day leave. "No sir, I'm afraid when I go home I'll have to go in the back door," Murphy is quoted as saying. "I couldn't go for being treated as a hero."

His hometown wasn't about to stand for that kind of humility. An AP story June 8 cited Farmersville mayor R.B. Beaver saying Murphy would "get the biggest reception any Farmersville boy ever got, 'whether he likes it or not.'"

"It would be just like that little rascal to try to get past our welcoming committee," the mayor continued. "He's terribly modest and quiet, you know -- doesn't go at all for the sort of thing we're preparing for him. Well, he'll just have to take it, that's all."

Murphy arrived back at Fort Sam Houston days later, and celebrations followed -- not just in Farmersville but around the country. His leave turned into a series of speaking appearances, and he quickly became a poster boy, heroic GI Joe returning home.

Murphy's fame exploded from there. James Cagney was intrigued by a blurb on Murphy's exploits in Life magazine and invited him to Hollywood. There, Murphy began dating an actress, Wanda Hendrix, who he would marry in 1949. That same year, he wrote his memoir, "To Hell and Back," and landed his first leading role, in "Bad Boy."

He eventually starred as himself in the 1955 film adaptation of his autobiography, and appeared in numerous other movies -- many of them Westerns -- into the mid-1960s.

Throughout this time, Murphy dealt with what he would now call post-traumatic stress disorder, enduring years of depression and nightmares stemming from his war experience.

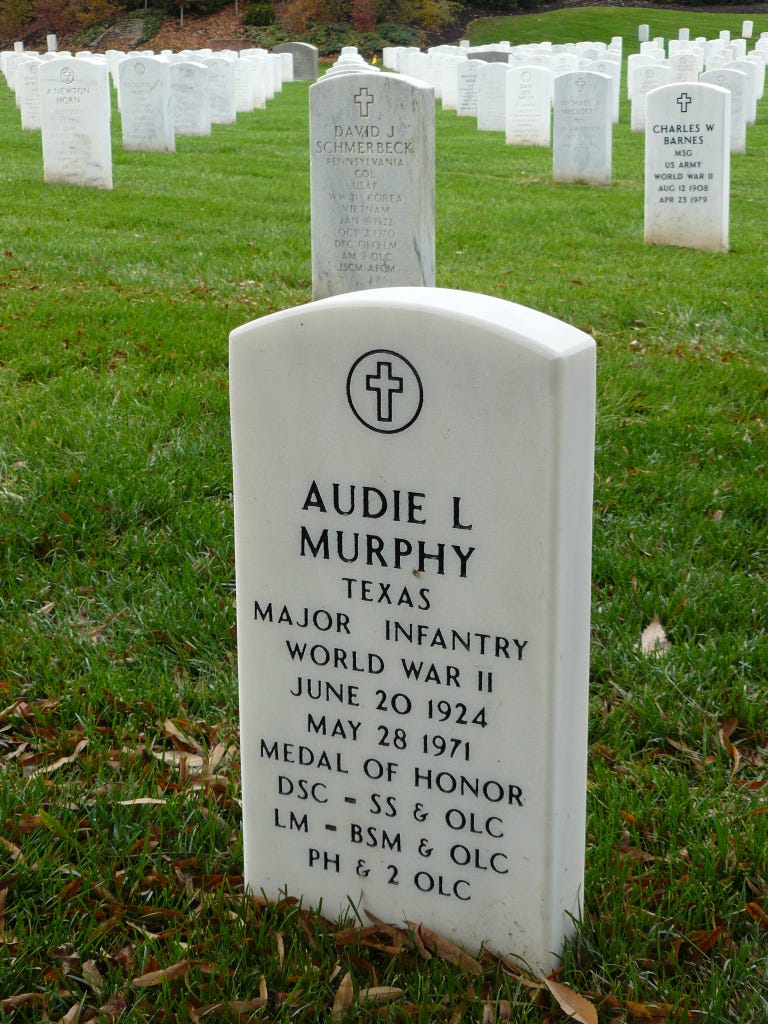

He died in a plane crash in West Virginia on May 28, 1971, only 45 years old, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.