On the morning of Saturday, May 5, 1945, Rev. Archie Mitchell and his wife Elsie packed five children from their Sunday school class at the Christian Missionary Alliance Church into their car and headed out on a fishing trip.

They drove east from Bly, Oregon, a little over 10 miles to a creek in what is now the Fremont National Forest, south of Gearhart Mountain. At some point, the rest of the party got out of the vehicle as Archie, 27, prepared to drive on to a parking spot.

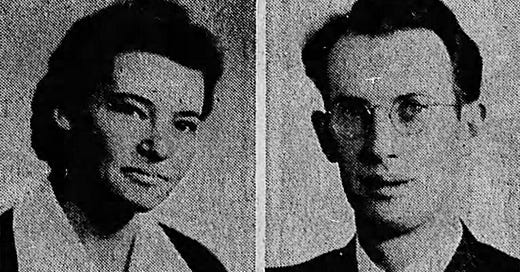

Elsie and the Sunday schoolers — Eddie Engen, Jay Gifford, Sherman Shoemaker, and siblings Joan and Dick Patzke, all between the ages of 11 and 14 — headed off to the woods. The group spotted something strange in the forest and called out, getting Archie’s attention.

“Joan came over and told us that there was a white object nearby,” Archie said, according to one account. “We went to investigate.”

He was about 40 yards away when the object exploded.

“It blew up and killed them all,” Archie said.

Eddie, Jay, Sherman and Dick, who were closest to the device, died instantly. Joan lay unconscious nearby but would not survive. When Archie arrived at the scene, he found his 26-year-old wife, who was pregnant with their first child, lying on the ground with part of her dress on fire. He managed to put out the flames, but Elsie was dead within minutes.

Elsie Mitchell and the five children had been killed by a Japanese balloon bomb. Just two days before the end of the war in Europe, they became the first — and only — people killed by enemy action on the U.S. mainland during World War II.

Word of the tragedy spread instantly through the surrounding area, but didn’t immediately make the news. The first press accounts appeared two days later, May 7, but the reports were vague.

The Klamath Falls News and Herald reported the victims were “killed instantly by an explosion of unannounced cause.”

A short Associated Press story simply called it an “explosion” but hinted at something more sinister with a cryptic final paragraph: “Army intelligence officers arrived and clamped strict censorship on all civilian authorities. No details were available.”

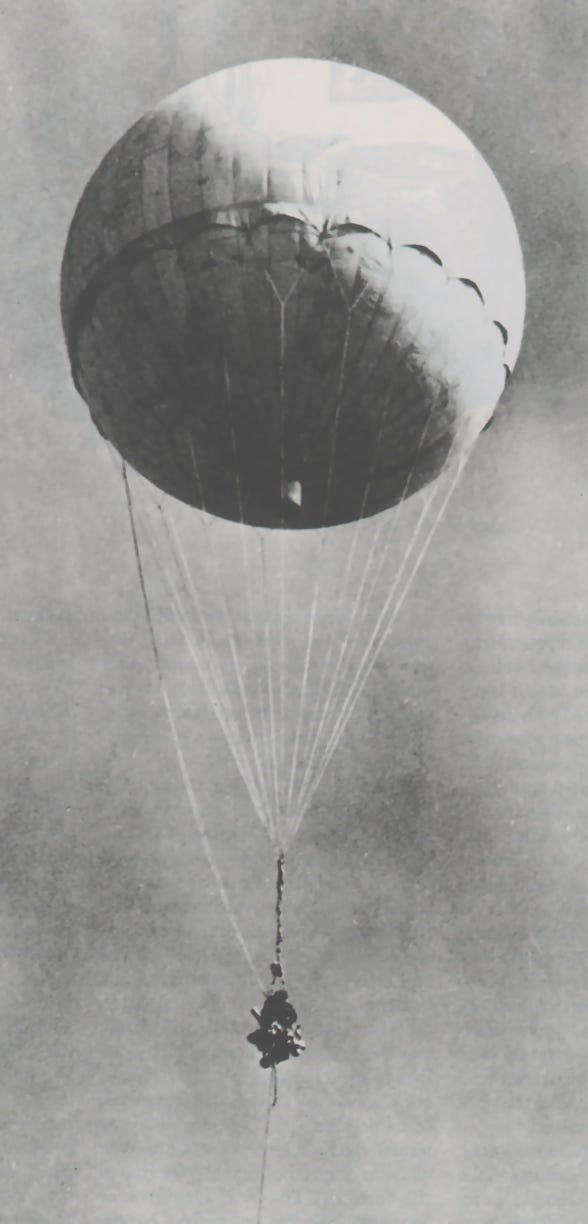

Hydrogen-filled balloons carrying explosive devices, a desperate attempt by the Japanese military to target the U.S. civilian population, began appearing on North American shores in November 1944.

They never had their intended effect, but U.S. officials wanted to ensure the Japanese wouldn’t be able to know one way or the other. After a few mentions of the balloons in the press that winter, censorship officials clamped down in early January 1945 and asked the American press not to mention any balloon attacks.

The strategy worked, to an extent. Japan ended the program in April 1945, believing it wasn’t worth the expense and effort. But the information blackout had an unintended consequence: While some Americans knew of the balloons’ existence through word of mouth, particularly those in the western U.S., many had no idea a fallen balloon might pose any kind of danger.

Investigators in Oregon believed one of the children kicked the device attached to the bottom of the balloon, causing it to detonate. The idea that more civilians might be harmed in similar incidents prompted the government to change course by the end of the month.

On May 31, Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson announced the true cause of the six Oregon deaths. He told reporters in Washington he was doing so to emphasize the need for precautions in such situations while still balancing a desire for military secrecy.

“It is our natural aim to keep from the enemy any information that will make his futile attack any more effective,” he said. “Any information at all which would indicate the time or place of the arrival of a balloon, or their numbers or their particular effects or anything on their technical aspects would aid the enemy to correct and improve their flight and mechanism and encourage their continuance.”

The locals in the midst of the tragedy weren’t having it. An editorial in the June 1 News and Herald penned by managing editor Malcolm Epley put the blame for the deaths squarely on the government:

We can be quite certain that the whole story of the Jap balloons came to light through the tragic incident near Bly in which six Klamath county people were killed.

Prior to that incident, the war department decreed an airtight censorship on the fact that the Japanese were trying to land these fantastic gadgets on the western coast of the U.S.

The censorship was so successful that it can be marked down today as responsible for the deaths of the five children and a minister’s wife in the woods near Bly. All indications are that none of them knew about Jap balloons and their dangers when they discovered one of the instruments lying in the woods near the Dairy creek road.

The editorial went on to say that the newspaper had wired the office of censorship the day after the explosion to ask that restrictions be lifted so the public could be informed. It’s not clear whether that specific request led to Patterson’s statement more than three weeks later, but either way it was too late for Elsie Mitchell and the children.

Reporters from the Herald and News spoke with Archie Mitchell and the parents of Jay Gifford on that final day in May. While Archie said he had heard rumors of such balloons and called out to his wife and the children not to touch the one they found, the Giffords said they were not aware of any balloons landing in the area.

“The people we talked to agreed that it was best that the whole story be told, so that the shocking tragedy might warn the public,” the newspaper wrote. “It has done that now, all right.”

The day after Japan surrendered in August, the Seattle Times published an extensive look at what it had learned about the balloon bombs in recent months, estimating that more than 200 had landed in the United States, Canada and Mexico, one drifting as far east as Michigan.

Most of the balloons carried four incendiary bombs, one anti-personnel bomb and a flash bomb to destroy the balloon itself. The first such device was discovered in Montana in December 1944, the paper wrote. On March 10, 1945, four separate balloons were recovered.

One particular anecdote in the report drove home the Herald and News’ argument that the censorship surrounding the devices may have done more harm than good:

In Yakima, Washington, a boy unknowingly carried around a Jap anti-personnel bomb he found for several days before white-faced authorities persuaded him it was dangerous. If he had twisted the armed bomb’s detonating device 1/16th of an inch it would have exploded.

In August 1950, the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, which owned the surrounding land, dedicated a memorial to the six bomb victims.

About 500 people attended the ceremony, but Archie Mitchell was not among them. He had remarried and moved to Vietnam in 1947 to continue his missionary work.

His new wife was the former Betty Patzke, older sister of bombing victims Joan and Dick. Their relationship blossomed amid trauma — not only the deaths of Betty’s two youngest siblings in the explosion, but the loss of her brother Jack around the same time.

Jack Patzke was aboard a U.S. B-17 that was shot down over Italy in April 1944 and spent months at Stalag Luft III. As the Red Army closed in on the camp in April 1945, Jack and other POWs were forced to March south ahead of the advance. He broke away from the column in Bavaria and was shot to death, a little over three weeks before the rest of his crewmates were freed by Gen. Patton’s Third Army.

About six months after they married at the Christian Missionary Alliance Church in Bly on June 1, 1947, Archie and Betty Mitchell shipped out for Southeast Asia. They would make their home in Vietnam even as tensions increased in the area, raising four children as they worked at a leprosarium near Ban Me Thout before tragedy struck again.

On the evening of May 30, 1962, a dozen Viet Cong guerillas entered the compound as the missionaries were preparing for their weekly prayer meeting. The soldiers ransacked the place, taking anything that might be of value and forcing Archie Mitchell and two other missionaries, Dr. Eleanor Ardel Vietti and Dan Gerber, to accompany them in a vehicle.

When Betty Mitchell was able to write to her family in Oregon, she began the letter this way: “Before I tell you about what has happened, let me say that God has given each of the children and myself real peace. We know that Archie is under His care.”

Rumored sightings of the kidnapped missionaries would persist for years, but nothing was ever confirmed and their remains have never been recovered.

Betty Mitchell maintained her faith, returning repeatedly to Ban Me Thout and asking everyone she saw if they had seen Archie. On March 10, 1975, she and five other missionaries were taken captive by Communist troops. They were held for months before being released in late October of that year.

As of April 30, 2021, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency listed 28 civilians still officially considered missing from the Vietnam War. Among them: Dan Gerber, Eleanor Vietti and Archie Mitchell.

“The exact locations and circumstances surrounding their deaths are unknown,” the DPAA’s website says, “and all three remain unaccounted-for.”

Whoa! I had NO idea!