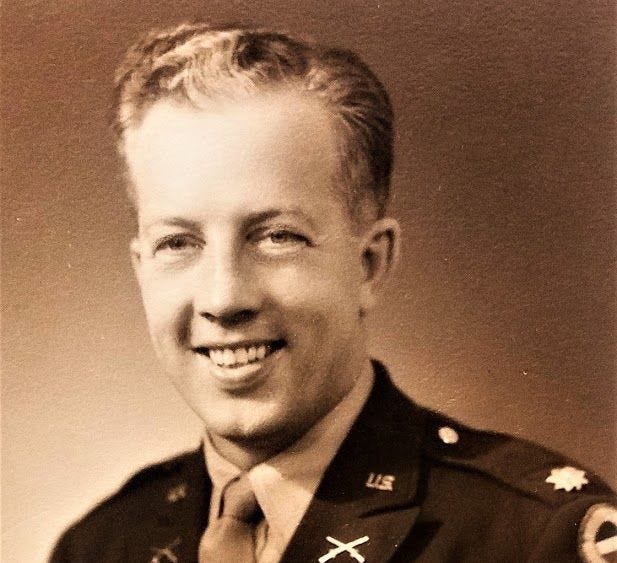

Barney Oldfield lived a remarkable life by any measure, as a guy from Tecumseh, Nebraska who ended up handling publicity for Hollywood stars like Elizabeth Taylor, Errol Flynn and Ronald Reagan, and becoming a close confidant of heavyweight champion George Foreman.

In addition to rubbing shoulders with celebrities like that, though, he also played a prominent role in Allied press operations during World War II.

Born Dec. 18, 1909, Oldfield got his start as a reporter working for newspapers in Lincoln and freelancing for Variety magazine. He was one of many wartime public relations officers (PROs) with a journalism background, but he definitely had a nose for public relations.

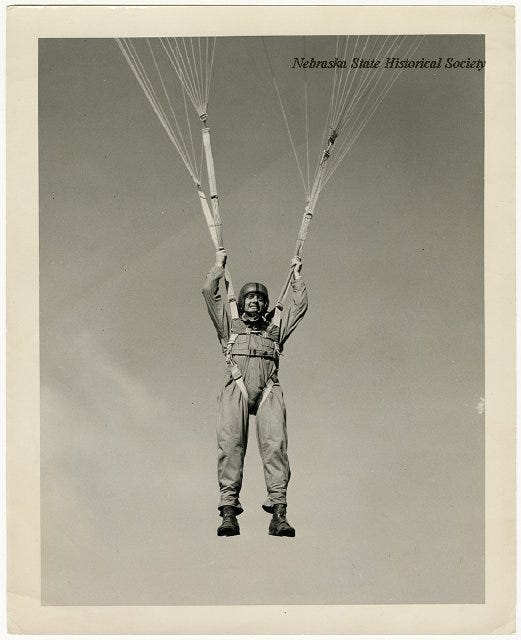

He became the first PRO to complete parachute training, then convinced several correspondents to do the same -- starting with Jack Thompson of the Chicago Tribune dropping into Sicily in July 1943. That innovation opened up new avenues for story and photo opportunities to trumpet the cause back home, and a handful of correspondents would participate in subsequent airborne operations the rest of the war.

His 1956 wartime memoir, Never a Shot in Anger, is an indispensable window into press relations during the war. In one passage, he describes one of his duties ahead of D-Day: welcoming correspondents to a London apartment block and having them write their own obituaries.

"This last request never failed to get a reaction. Some of them took it in high good humor to cover their real feelings, others straight, and some were shaken. ...

"William Stoneman of the Chicago Daily News syndicate refused to do it unless his old friendly enemy competitor H.R. Knickerbocker, the veteran International News Service circuit-rider who had gone to the Chicago Sun, turned in more than four pages on himself. Knickerbocker's piece ran four and a half, whereupon Stoneman still balked. 'Just say I was all the places Knick was,' he said, 'and usually filed first, too.'"

Once a foothold had been established in Normandy that summer, Oldfield moved to the continent, presiding over a series of press camps as the war in Europe ground to its conclusion in May 1945.

“When the war ended, my driver, Corporal Max O. Shepherd, reported that the speedometer [sic] on our jeep was standing at 24,981 miles,” Oldfield wrote.

He remained in the military after the war, transferring to the Air Force in 1949, and served in Korea before taking over public relations at NORAD.

Oldfield died in 2003 at age 93, but his legacy endures. He and his late wife Vada, a fellow University of Nebraska graduate, established a scholarship at the school that has since grown into numerous funds benefiting university students and researchers.

23 Years ago I was honored to host Col. Barney Oldfield at a luncheon of the Nebraska delegation to the 2000 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. Each day of the Convention, the Nebraska delegation honored a Nebraskan living in Los Angeles. Col. Oldfield was a True Nebraskan. I met him at the entry of the Beverly Wilshire hotel where he drove up in a bright red classic Cadillac with Barney wearing a bright red suit and a red fedora. He was so proud to be honored by his fellow Nebraskans.