Crossing the Rhine: The bridge at Remagen

War correspondents and the public relations officers assigned to manage them generally did everything they could to ensure coverage of the key moments of World War II, but news doesn't always come with advance warning. That certainly was the case for one of the most anticipated stories in the latter stages of the European war: Allied troops crossing the Rhine for the first time.

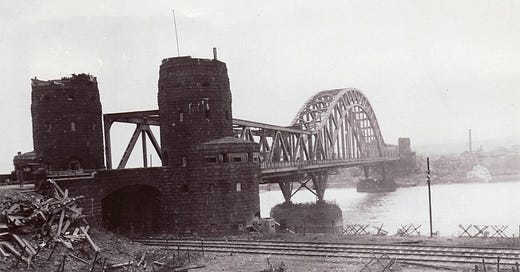

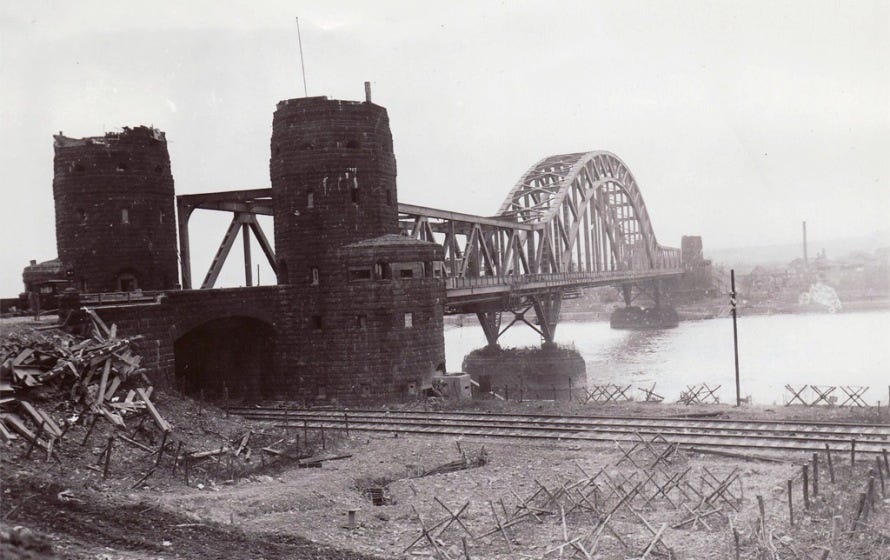

It occurred just before 4 p.m. local time on March 7, 1945 via the Ludendorff Bridge, which linked Remagen on the west bank with Erpel on the east bank, about 35 miles southeast of Cologne. The U.S. 1st Army's 9th Armored Division had advanced rapidly toward the iconic river, and scouts arriving in Remagen around midday were stunned to see the bridge was still standing.

After Germans scrambling to retreat failed in their efforts to demolish the bridge, a small party of Americans made their way across that afternoon and gained a foothold on the east bank. It would be a few hours before word of their unexpected feat made it all the way up the chain of command, setting in motion not only a frenzy of activity to reinforce the initial bridgehead but a mad scramble by correspondents to reach the scene.

Those who had covered the fighting in Cologne had an advantage in that race, and Howard Cowan of the Associated Press won it -- edging out Andy Rooney of Stars and Stripes. The 30-year-old AP correspondent not only reached Remagen first, but hustled over the bridge to Erpel and back before any of his brethren. That was enough to secure the coveted dateline that first appeared in some U.S. evening editions on March 8: ACROSS THE RHINE.

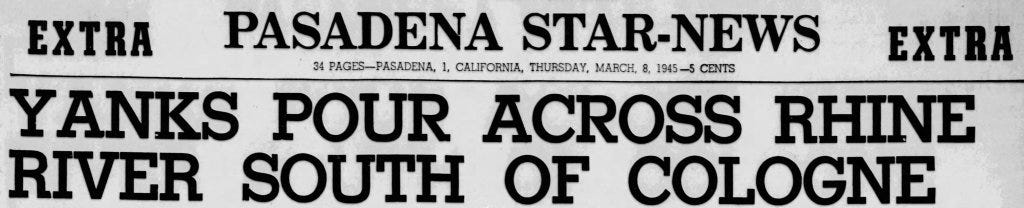

The crossing generated banner headlines back home. The Pasadena Star-News even published an extra edition, featuring Cowan's byline, dateline, and a single sentence of copy: "Elements of Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges' American 1st Army were firmly entrenched on the east bank of the Rhine tonight."

The initial reports cleared for publication were based on official communiques and written out of Paris, hitting the wires after censors released the news just before 6 p.m. local time March 8. Though forbidden from specifying exactly where the great river had been breached and lacking in on-scene detail, they summed up the historic magnitude of the achievement. Wrote Drew Middleton in the lead story in the next day's New York Times:

The forcing of the Rhine should be a heavy blow to German morale. Hundreds of stories and legends of German folklore are set in the Rhine valley, and the great river was an impassable defensive barrier in the minds of the Germans.

Not since 1805, when Napoleon swept across Europe from the English Channel coast to rout the Austrians at Ulm, has the Rhine been crossed by an invading army. To the Germans of the Second and Third Reichs it was a safeguard against invasion stronger than any Hindenburg or Siegfried Line.

The bulk of the press corps endured a frustrating journey to cover the news of the day -- to the point that Hal Boyle of the Associated Press filed a separate story on chasing the story.

After leading with his colleague Cowan's triumph in arriving first, Boyle noted that it took 14 hours for the jeep carrying Jack Thompson of the Chicago Tribune, Harold Austin of the Sydney Morning Herald, and himself to cover the 225-mile round trip from the press camp. The party navigated "through traffic jams, over side roads and around detours. We had two flat tires and had to hoof the last two and one half miles."

Chris Cunningham of United Press and Bill Downs of CBS also saw their jeep sidetracked by a pair of flats, forcing them to beg a replacement tire from an ordnance company. Rooney and Gladwin Hill of The New York Times, meanwhile, got lost on the way back and nearly drove through German lines.

"We were gone altogether 17 1/2 hours and spent only 20 minutes actually getting the story," Rooney told Boyle. "The rest of the time we spent in the jeep."

But it was a big enough story to compel that kind of effort, its import summarized this way by Boyle:

Newspaper men assigned to the 1st Army returned to the press camp after a long day of jeeping over muddy roads with enough diluted German real estate on their faces to start a potato farm.

The story was so hot, however, they had no time to get rid of the accumulated topsoil until they had finished pounding out their accounts of this most surprising and enterprising military adventure of the war.

It wasn't just newspaper men making the journey, incidentally. One of the most comprehensive accounts of the Rhine crossing came from Iris Carpenter of the Boston Globe, whose story dominated the paper's March 10 front page.

"Experts had worked as long and hard on organizing for the Rhine crossing as for the invasion itself," she wrote. "When it finally happened, there was no need for special plans or any of the spectacular methods we could have used. Our men just walked over."

Carpenter then reconstructed the scene she and the others had missed: Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division rolled into Remagen on March 7 and found German soldiers and vehicles fleeing across the bridge. Around 3 p.m., a prisoner informed his American captors that the structure was to be blown at 4 p.m.

German defenders did manage to set off some explosives before then that damaged the bridge, but it remained intact. American troops from A Company of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion charged across not knowing whether their path to the far shore would blow up in their faces.

Initial press dispatches credited 2nd Lt. Emmett J. Burrows with being the first man across the Rhine, but one of his noncoms, Sgt. Alexander Drabik, was later determined to have taken the honors after sprinting the entire length of the bridge.

Drabik grew up on a farm in Holland, Ohio, some 10 miles west of Toledo, where he had worked in a slaughterhouse before joining the Army in 1942. (We know this because the AP felt compelled to move a separate story on Drabik on March 10 after the world learned of his heroics.)

Most importantly, that initial raiding party managed to hold its position, and the Germans didn't immediately mount a counterattack. They continued to shell the bridge sporadically for days to come, but the structure endured as American infantry and armor poured across.

Correspondents, too -- at least so they could claim that dateline, as Cowan had. Iris Carpenter described her crossing this way:

Traffic over the bridge, meanwhile, is one way -- eastward. Hence this correspondent found herself walking over the Rhine with the invading infantry. From the time we moved under the twin grey stone turrets at the western end, past the body of a German shot as he tried to blow up the bridge, and out under the turret at the eastern end, it was five minutes.

I thought they were the longest five minutes I had ever spent until the five it took to get back.

There was altogether too much noise of battle to absorb more than a brief impression, let alone appreciate the scenic background to that battle -- white and yellow villas tucked into crumpled hills, churches looking like the ones you buy as Christmas-cake decorations.

In his main news story on the acquisition of "one of the most important bridgeheads in military history," Hal Boyle also cited the picturesque landscape, but his primary tone was one of disbelief that it had been possible at all.

The Germans fumbled. They were caught by surprise -- caught flatfooted by this great gamble which has turned into a brilliant coup.

There is rugged beauty at the site of this crossing -- sheer bluffs and rolling green hills above the silver river. But that very ruggedness could have made this crossing site all but impregnable, had the Germans been ready. The best they could muster was the intermittent artillery fire and this has been ineffective in halting Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges' power plunge.

The primary thread that ran through every account of the crossing was that the Rhine was far more significant than just a line on the map. One correspondent after another expressed the hope that this might actually be the beginning of the end of the fighting.

"The German civilians stare in consternation at the parade of American might, but they show little sympathy for their dead soldiery," Boyle wrote. "These people are too sick of war and bloodshed to care much now who gets killed. They only hope dully that the war will be over soon."

Thousands more on both sides would die in the coming weeks, but exactly two months later, the war in Europe finally was over.