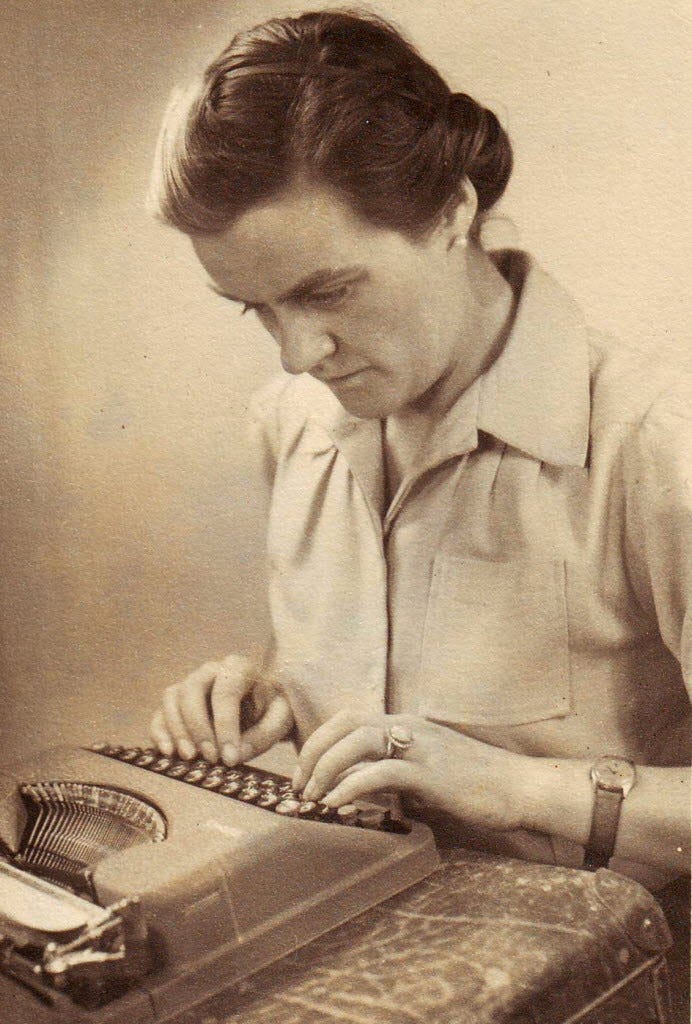

Clare Hollingworth and the scoop of a lifetime

Less than a week into her first full-time job as a journalist, Clare Hollingworth rode out of Poland in a borrowed car on August 28, 1939, crossing the German border at Beuthen and heading toward Gleiwitz (now Bytom and Gliwice).

The 27-year-old Englishwoman had spent months in Katowice earlier that year helping refugees from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia escape to Britain and elsewhere around Europe. Though social work was her focus at the time, Hollingworth had done some writing on the side. Back in the UK in early August 1939 she happened to run into Daily Telegraph editor Arthur Watson, who hired her to covering the rapidly deteriorating situation in Eastern Europe.

Days later, Hollingworth flew from London to Berlin and on to Warsaw, where she caught a train to Katowice. She sought out the British consul-general, John Anthony Thwaites, and talked him into lending her an official car and driver so she could get a firsthand look at what was happening around the German border. The "official" part was important, as the border had been closed to civilians but remained open to diplomatic traffic.

They were between Gleiwitz and Mährisch Ostrau (now Ostrava, Czech Republic) when what she described in a 2001 interview with the Imperial War Museum as a "sudden, strong gust of wind" led to a jarring sight: screens of netting that had been strung in the forest to conceal what was behind them tore away from their rigging. "I looked into the valley and saw scores, if not hundreds, of tanks lined up ready to go into Poland. I drove on, drove back through the border into Poland, and I said to the consul-general, 'Thank you for lending me your car.'"

Hollingworth told Thwaites what she had seen and advised him to telephone Warsaw and London "immediately," which he did. She then got in touch with Hugh Carleton Greene, the Telegraph Berlin bureau chief who had been expelled from Germany in May and was now in Warsaw. Hollingworth relayed what she had seen, and the two talked through the story he would assemble and send on to London.

The story, under the customary anonymous byline "From Our Own Correspondent," appeared on the front page of the Daily Telegraph on August 29. The headline read: “1,000 Tanks Massed on Polish Frontier," with the sub-headline: "Ten Divisions Reported Ready for Swift Stroke.” It began:

I learn on reliable authority that Germany has now concentrated 10 mobile divisions, including nearly 1,000 tanks, on the Polish frontier near Machrisch Ostrau. This force is apparently intended for a sudden stroke North-eastwards against Polish Upper Silesia and the important industrial area of which Katowice is the centre.

Hollingworth went on to describe her excursion across the border, noting that "intense military activity" was visible and the only cars she saw belonged to the German military. Then there was this ominous observation:

New fortifications which were not there a month ago have been erected all along the German side of the frontier. There are many tank traps and machine-gun nests and miles of electrified barbed wire.

On the Polish side of the frontier everything is comparatively normal.

The news undoubtedly shook those in the West who were still holding out hope that peace would prevail despite Hitler's increasingly aggressive posture, but the story itself didn't necessarily get flashed around the world. Many U.S. newspapers ran a one-paragraph item filed out of the United Press bureau in London summarizing the story in their August 29 editions, but most of the coverage focused on diplomatic channels.

At least until all hell broke loose three days later.

It should come as no surprise that Clare Hollingworth was on the scene as war officially broke out the morning of September 1.

In the clip below, from a 1978 BBC documentary, she talks with Hugh Greene about witnessing the war's opening moments.

Not mentioned in that clip is one bit that has become part of her legend. After getting off the phone with Greene, she called the British Embassy in Warsaw herself and spoke to an official who also was skeptical of her claims.

As proof, she reportedly held her phone out the window to pick up the sound of anti-aircraft fire and shouted, "Listen! Can't you hear it?"

Again, remember that Hollingworth was essentially in her first week as a professional correspondent as all of this transpired. But she caught the bug and it never let go.

As war rolled across Europe, Hollingworth blended humanitarian work with journalism, eventually jumping from the Telegraph to the Daily Express. She reported from Romania, Bulgaria and Greece before moving on to Egypt, where she reported for Kemsley Newspapers.

Even after the war, conflict proved an undeniable attraction. Beginning in the mid 1940s, she covered bloodshed from Palestine to Algeria to Malaya to Vietnam, then moved to China in 1972 to serve as the Telegraph's first correspondent there since 1949.

Hollingworth eventually moved to Hong Kong, where she continued to write occasionally for various outlets until her eyesight and hearing began to fade. She lived there for the rest of her life, dying January 10, 2017 at the age of 105.

RECOMMENDED READING: Patrick Garrett, Hollingworth's great-nephew, published a biography of her in 2016 entitled Of Fortunes and War.