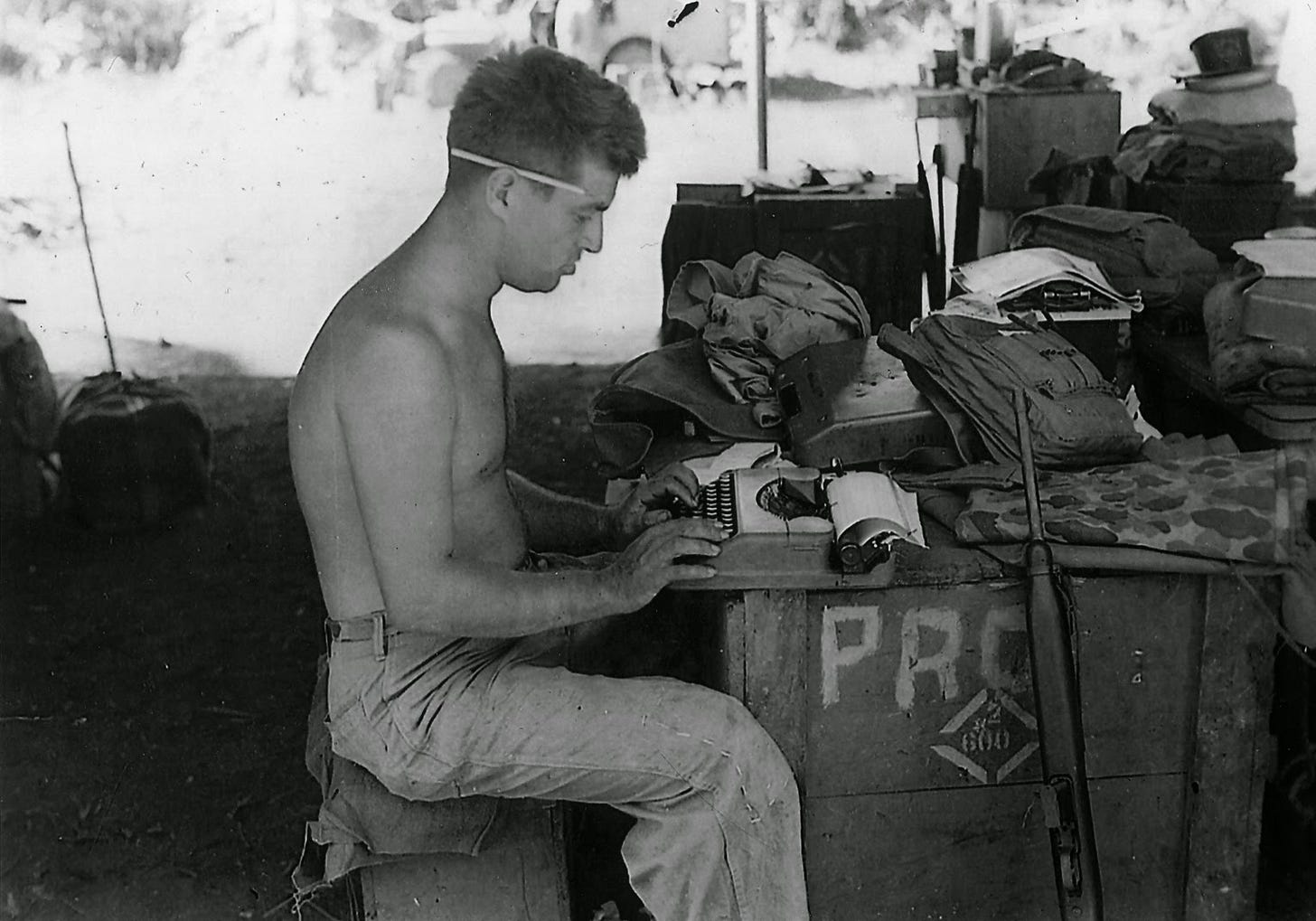

Cyril O'Brien, Marine combat correspondent

Upon graduating from Saint Joseph’s College (now university) in Philadelphia in June 1942, Cyril J. “Cy” O’Brien nursed twin career ambitions: He wanted to become a journalist, and he wanted to be a Marine. The war would allow him to realize both goals simultaneously.

Born Jan. 30, 1919 in Newfoundland, O’Brien moved to the U.S. as a child. His family first lived in Massachusetts before settling in Camden, New Jersey, where O’Brien would attend Camden Catholic High School. He spent years delivering the Camden Courier-Post, then went to work in the newsroom as a copy boy while he attended journalism school at Saint Joe’s.

A blurb in the newspaper shortly after he graduated from college noted that O’Brien had been turned down by the Marines three times for being too short. (His draft card lists him at 5-foot-6, but that apparently was a bit of a stretch.) But he finally got his wish about a month later and enlisted, serving initially as an infantry scout after completing his training.

By the spring of 1944, Pfc. O’Brien was reporting from the Pacific as a combat correspondent. His stories were mostly of the “hometown” variety, shorter pieces spotlighting individual Marines that were then distributed to regional newspapers. His signature work, though, came during the fight to recapture Guam that summer.

O’Brien accompanied the 3rd Marine Division throughout the operation, which officially lasted only three weeks but in reality dragged on for months as Marines hunted down Japanese stragglers. He became known among his superiors for disappearing for two or three days at a time as he joined combat patrols around the island. But he always returned, with a story to tell.

“Dawn arrived and it was raining,” he wrote of one patrol. “We were whispering that it was almost time for the other platoon to relieve us when a single shot interrupted. Pfc. Carl Letting, 17, Flint, Mich., kneeling in a corner of his foxhole, had a pistol in his hand. Twenty yards away a Jap hung like a rag doll over a clump of brush. Two others gazed, petrified for an instant, at their dead companion, then crashed into the brush.”

In early 1945, Adm. Chester Nimitz cited O’Brien — who had since been promoted to sergeant — for meritorious service during the Guam campaign. The commendation read in part:

With complete disregard for his safety, he exposed himself to constant danger by covering the fighting wherever it was thickest. After troops secured for the night, he wrote his stories in outstanding detail which called attention to and preserved for history the heroism of observed individuals and units.

To further delineate the action of his unit, he accompanied combat patrols on mopping-up missions after organized enemy resistance on Guam was declared ceased. His conduct was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States naval service.

“It’s a pleasure to let the folks back home know what a tough bunch of fighters the Marines are,” O’Brien was quoted as saying in a Courier-Post story on the commendation.

After spending months on Guam, O’Brien would go on to cover the Iwo Jima campaign before heading home to Camden on a 30-day furlough near the end of July. While he was there, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war.

O’Brien was back at work on the Courier-Post by fall and would later write a book about the campaign, Liberation: Marines in the Recapture of Guam.

Over the next few years, O’Brien worked for other newspapers in New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania before moving to Washington, D.C., in 1948. The following year he left newspapers to work in media relations at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, where he would remain a fixture for the next 34 years.

After retirement, O’Brien continued writing for a variety of publications into his 90s. He died Jan. 31, 2011 at age 92.