D-Day: Correspondents balance ambition, fear ahead of invasion

The classic bit that sums up the tension between the press and its handlers ahead of the Normandy Invasion first appeared in Leonard Lyons' syndicated column on June 12, 1944:

Shortly before the invasion began, Britain's Ministry of Information was besieged by hundreds of newspapermen seeking credentials to cover the story. For a while the confusion seemed interminable. One disgruntled correspondent finally approached an official and complained of the lack of cooperation.

"Don't you realize," the newspaperman ranted, "that this is the most important story since the Crucifixion?"

"Yes," replied the British official, calmly, "but remember -- only four men covered that."

The exchange feels apocryphal, but surely rang true with the reporters and photographers jockeying for prime coverage positions around the war's most anticipated day.

"One of the troubles in the mounting up for Normandy was the great number of war correspondents who wanted, or professed to want, to be in the so-called 'first wave,'" public relations officer Col. Barney Oldfield would later write. "In it was the lure of the front-page by-line and the established reputation for all time."

Though the details of when and where the attack would occur remained the Allies' most closely guarded secret, the fact that there would be an invasion -- almost certainly in France -- had long been taken for granted by both sides. And plans for how to cover it had been in the works for months.

An Associated Press story moved from London on April 7 put it concisely: "The coming invasion of Europe will have the most comprehensive news coverage of any military event in history."

The piece went on to note that 306 "newspaper men, magazine writers, radio reporters and photographers" had been accredited by the U.S. Army, some 215 of those working for U.S.-based outlets. That was far from the full complement, though, as the U.S. Navy and the British military also had correspondents assigned within their ranks.

Among those scores of correspondents, only a relative handful would actually set foot in Europe on D-Day itself. Transportation and communication logistics dictated that limitation, making on-the-scene assignments particularly sought-after.

On May 2, the AP moved a story laying out how it planned to cover the invasion, trumpeting its four men selected to go in with the first wave: Don Whitehead, Roger Greene, William S. White and James F. King. It went on to name those who would handle the aerial attacks, who would be at sea, and who would be at SHAEF headquarters. Among the latter group was Edward D. Ball, then serving as the day editor at the London bureau.

The assignment frustrated Ball, who longed for something closer to the action. As it turned out, he would get it. Within a few weeks, the AP adjusted its alignment, with Ball now assigned to a PT boat patrolling the English Channel. He wrote to his family in Georgia in a letter dated May 26, saying he was "thrilled" with the change:

At first it looked like I would have to sit in the office editing and rewriting the other fellows' copy. But now unless the lineup is changed -- and there is always that possibility, the way they do things -- I will have a chance to do the job I came over here to do.

Edward D. Ball family papers, University of Georgia

Ball's sense of professionalism -- if you're going to cover the invasion, you really want to cover the invasion -- is understandable and admirable. But make no mistake: even the journalists longing to be in the thick of the action had reservations, to say the least.

Walter Cronkite, then a United Press correspondent covering the air war, found himself in a similar situation to Ball as invasion fever grew. He wrote about it four decades later.

I had been denied a place among those correspondent heroes selected to make the landing with the troops on D-Day. "Denied" may be too strong a word. It was the most dangerous assignment of the war and every correspondent knew it, and when the chance of glory was weighted against innate cowardice, glory sometimes lost its priority.

But this choice wasn't mine to make (this perhaps saving me from besmirching the family escutcheon). I was assigned to stay back at United Press headquarters in London's Fleet Street to help write the lead stories, pulling together what we all knew would be a confusion of reports from the beaches and the military commands.

As it turned out, Cronkite did get a taste of the big show. He was awakened by a public relations officer at 1:30 a.m. on June 6 and rushed to an airfield. SHAEF planners had decided to send another wave of bombers over the invasion beaches, and officials had decided to offer a correspondent the opportunity to accompany them. They picked the UP out of a hat from a group of six news organizations, and Cronkite -- who had flown with bomber crews before -- got the call.

There was so much cloud cover over the French coast that Cronkite could hardly see a thing -- though he did catch a brief glimpse of the invasion armada on the way over. His "eyewitness" story didn't amount to much, and Cronkite vented in a June 12 letter to his wife, Betsy: "... I did not see a single thing. I was never so disgusted in my life."

There were those who got much closer than a boat's-eye view of the invasion beaches, though. Time and Life correspondent William Walton jumped into France with Gen. James Gavin and the 82nd Airborne, while the BBC's Chester Wilmot landed with British troops in a glider.

Ken Crawford of Newsweek went ashore on Utah Beach, Doon Campbell of Reuters hit Sword Beach with Lord Lovat's Commandos, and Don Whitehead of the AP and Jack Thompson of the Chicago Tribune landed on Omaha Beach with the 1st Infantry Division. Robert Capa captured his famous photos off Omaha as well.

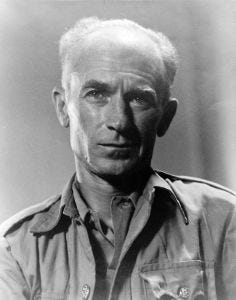

America's most beloved war correspondent, Ernie Pyle, expected to be among that group as well. Aboard an LST in the Channel, he listened with conflicting emotions as a colonel laid out the invasion plan -- "the secret the whole world had waited years to hear, and once you have heard it you permanently become a part of it. Now you were committed. It was too late to back out now, even if your heart failed you."

Pyle's humanity was the primary reason he was able to connect with grunts and grandmothers alike, and he didn't bother with bravado in this column, which ran June 13 in many papers.

I asked a good many questions, and I realized my voice was shaking when I spoke but I couldn't help it. Yes, it would be tough, the colonel admitted. Our own part would be precarious. He hoped to go in with as few casualties as possible, but there would be casualties.

From a vague anticipatory dread the invasion now turned into a horrible reality for me. In a matter of hours this holocaust of our own planning would swirl over us. No man could guarantee his own fate. It was almost too much for me. A feeling of utter desperation obsessed me throughout the night. It was nearly 4 a.m. before I got to sleep, and then it was a sleep harassed and torn by an awful knowledge.

Due to a "last-minute altered arrangement," as he put it in his first piece written from France, Pyle didn't make it ashore until the morning of June 7, by which point the beaches had calmed considerably. Once reunited with his correspondent pals in Normandy, that feeling of desperation would fade. Until the next time.

Check back all week for more D-Day stories as World War II on Deadline commemorates the 76th anniversary of Operation Overlord