D-Day: Joan Ellis and the AP's accidental invasion flash

The flash hit the Associated Press wire at 4:39 p.m. Eastern War Time on Saturday, June 3, 1944:

FLASH LONDON EISENHOWER'S HEADQUARTERS ANNOUNCED ALLIED LANDINGS IN FRANCE

U.S. broadcast news operations had been poised for just such an alert for weeks, and immediately sprang into action. Seconds after the flash hit the wire, CBS broke into the Belmont Stakes broadcast to announce the news. NBC and the Blue Network also broke into programming immediately. Radio stations in parts of Latin America that had also received the bulletin did the same.

Less than two minutes after the initial burst, though, the same teletypes clattered with the message "BUST THAT FLASH", the first in a series of desperate follow-ups. At 4:44 p.m., a message to KILL the flash. At 4:48, "KILL THE FLASH AND BULLETIN FROM LONDON ANNOUNCING ALLIED LANDINGS IN FRANCE". A minute later: "A KILL IS MANDATORY. MAKE CERTAIN THE STORY IS NOT PUBLISHED". And a minute after that, an advisory saying the flash was the result of a "TRANSMISSION ERROR".

The AP would continue its efforts to jam the bullet back into the gun, but it was too late. One of the most notorious journalistic blunders in history was already in the wind.

From the front page of the next day's Miami News:

In the few minutes between the erroneous radio report and the cancellation of the flash, soldiers and sailors in hotel lobbies and at military posts who heard the report slapped each others' shoulders, "yippeed" and expressed great satisfaction that the invasion was at last under way. They refused for many minutes to believe the announcement that the report was erroneous, and insisted that the first report was probably correct.

At 5:38 p.m. EWT, the AP provided a full explanation:

A mistake by an inexperienced London telegraph operator caused the Associated Press to move on its wires today an erroneous flash announcing that General Eisenhower's headquarters had announced Allied landings in France. ...

The Associated Press London bureau advised that the erroneous message had been sent by a new girl teletype operator in a wholly unauthorized test of a teletype punching keyboard. It moved without the authority of the censors and without knowledge of the A.P. editorial staff, which had no such copy on hand.

Experienced operators saw the flash on the printer in the London office and immediately notified New York and the London editors, who sent a bulletin 'kill.' ...

The young A.P. operator, Joan Ellis, a British subject, who erred, said she had been practicing on a disconnected machine and thought she had torn up the perforated tape, which transmits the electrical impulses of a teletype machine.

However, she then started to transmit the first take of the Russian communique, and said she inadvertently ran through the transmitter the strip of take containing the erroneous flash.

With that bit of recrimination -- helped by the actual invasion coming two and a half days later -- Joan Ellis immediately became a key footnote in the history of the war's most anticipated day.

On the job for about four months, the 22-year-old former WAAF teleprinter operator suddenly found herself the center of an international uproar. Though British newspapers initially refrained from printing her name, she was on the front page across the United States beginning the evening of the 3rd and her home country soon followed.

By Monday, June 5, British papers had jumped aboard. The Daily Mirror noted it had sent a reporter to her flat in Camden Town's Rochester Road on Sunday, but alas she was "out" at the time.

The International News Service had better luck on Monday, scoring an interview with Ellis "on the worn, brownstone steps of her little, middle-class home."

A mortified Ellis explained once again what had gone wrong, saying she thought if she got practice typing up the invasion news ahead of time, she wouldn't be so nervous when the actual news arrived: "I knew they would want me to be quick with the message then."

The brown haired girl's eyes filled with tears and she said:

"The last thing I would have wanted to do was to upset the American people. I like Americans and I liked working with them. It is hard to believe I was the cause of such a terrible false alarm. I've been in a terrible muddle ever since and so has my family. ...

"I just don't know what to do with myself. I do hope the American people forgive me. I was only practicing because I wanted to do a good job when the time came."

An AP story that moved on the 5th quoted Ellis saying she hoped to return to work in a few days and "try to convince myself that I can do the work in spite of the strain of having made such an error that caused so much trouble."

The AP's chief rival, the United Press, reported on the miscue but didn't treat the error as a tabloid rival might. It reported in a June 5 dispatch that Ellis had collapsed at the office shortly after sending the bulletin and was "ill at her home" Sunday.

UP's story noted that the flash already had been compared to Orson Welles' "War of the Worlds" and multiple outlets compared it to a premature UP report that claimed an armistice had been reached in November 1918, days before the Great War actually ended.

The report also became a popular topic for Monday morning quarterbacking, with multiple U.S. papers penning editorials on the topic. The Asheville Citizen-Times' offering invoked both Welles and the armistice story as it sounded a warning about the dangers of the immediate spread of news reports:

If The Associated Press seems somewhat ungallant in blaming a lady it is only for the sake of clearing up a most embarrassing mistake.

The incident, however, ought to serve as a warning. A rumor denied 120 seconds after it had been circulated is a flimsy article indeed. Yet millions of Americans went off half-cocked. It took hours to undo the radio mischief of seven spoken words.

The Baltimore Evening Sun, on the other hand, blamed the whole episode on Ellis' gender. In a mind-boggling June 5 item, the editorial board notes she is "not the first of her sex to yield to the temptation to do what she had been distinctly told not to do" and compares her to Eve, Pandora and Lot's wife.

From this we may conclude that Miss Ellis' fault lies chiefly in the fact that she is a woman. But wait. Before men proceed to pat themselves on the back for keeping a firm hold on their curiosity, let them remember that it was a tailor, and a man, who peeped at Lady Godiva and lost his sight.

By the following morning, though, Joan Ellis was forgiven -- if not yet forgotten.

As the actual invasion of Northwest Europe got under way, the AP took time to compile a series of messages it had received from U.S. newspaper editors expressing their support for Ellis and move it on the wire on D-Day.

Among those quoted was James P. Rosemond, managing editor of the Akron Beacon Journal: "Based on Joan Ellis' statement asking 'America to forgive me,' suggest AP editors cable message to her. Ours would be 'No one in Ohio concerned about invasion flash. Good luck and carry on.' "

The Miami News reported on its own cable sent to Ellis, which read in part: "Cheer up. All is forgiven! You didn't miss it much!"

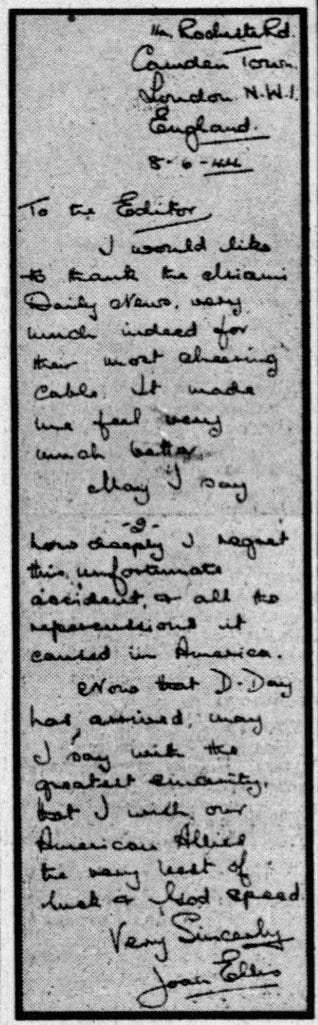

On June 29, the News printed the message it had received back from Ellis on June 8, which thanked the paper for helping her feel "very much better" and wished "our American allies the very best of luck and God speed."

Late on June 6, AP London bureau chief Robert Bunnelle was summoned to UK Minister of Information Brendan Bracken's office for what turned out to be a reassuring chat.

As Bunnelle recounted in a June 3, 1973 story for the Asheville Citizen-Times, where he served as president and publisher, Bracken told him the erroneous flash "fit in perfectly with Allied cover plans" for the invasion.

"The Germans couldn't believe it was a mistake and they had all sorts of people running around all over the French coast for days on end, wearing out supplies and manpower. And when we did invade, they were weakened by their previous effort. As a matter of fact, it fit in so well with our plans that, if you hadn't blamed the false flash on a British girl, we might have said it was part of our cover program."

As a matter of fact, I don't think it was, but I'll never know for sure.

That closing line from Bunnelle is worth a raised eyebrow, especially considering the conspiracy theories that surfaced briefly in various outlets in the weeks following the invasion.

More than one pundit called into question the plausibility of such a flash making it through the painstakingly constructed system of checks designed to prevent exactly that type of error.

In the New York Daily News, for instance, gossip columnist Danton Walker's June 23 piece included these two sentences:

The story of Joan Ellis, the English gal who broke the invasion story three days ahead, is a piperoo, but it can't be told until after the war. Meanwhile, is there such a person?

It's worth noting that Bunnelle rehashed the above story 11 years later in the Citizen-Times, reprinting that quote from Bracken verbatim. But this time, the story ended there, without the extra line about not knowing for sure.

As to whether there actually was such a person, Ellis' name did indeed disappear from the public eye as the battle for Normandy intensified. But for what it's worth, several newspapers ran this one-sentence brief in the fall of 1954:

Joan Ellis, who accidentally sent the false European invasion flash from London in 1944, is now Mrs. David Tourt, of Burton-on-Trent, England, and the mother for four children.