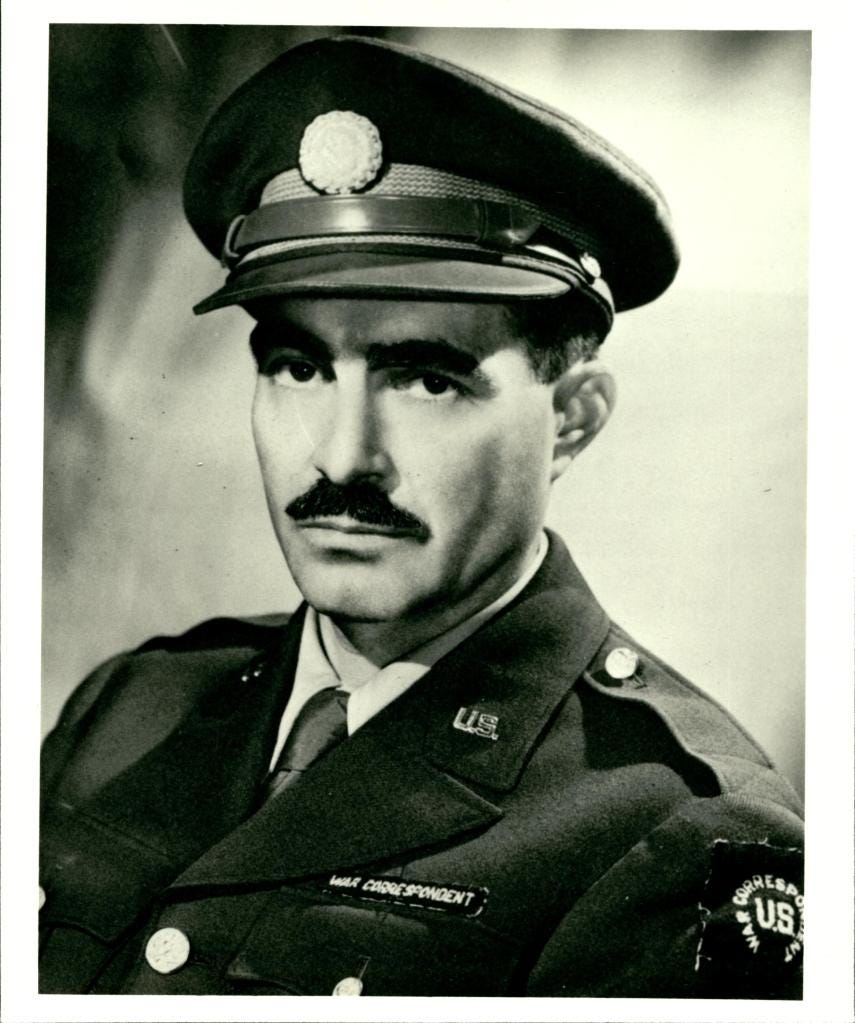

D-Day: Utah Beach with Ken Crawford

As the landing craft heaved in the English Channel, the slate-gray canopy overhead a reminder of the weather that already had pushed their mission back a day, Kenneth Crawford gazed down at his boots. Six inches of seawater and vomit rolled back and forth in time with the flat-bottomed boat, a compelling invitation under most circumstances to exit as quickly as possible. But as the 42-year-old looked up to peer over the bow, he saw a wide beach strewn with obstacles. Allied planners had code-named it Utah, and Crawford was about to join 32 soldiers in storming it.

One of them noticed that Crawford wasn’t armed and offered him a bag of hand grenades, which the older man declined. “Can’t use them,” he shouted. “War correspondent. Rule against it.” To hell with the rules, the incredulous soldier replied, “You got to have something if you haven’t got a gun.” When Crawford again demurred, the soldier gave him a look “that seemed to combine pity with disgust.”

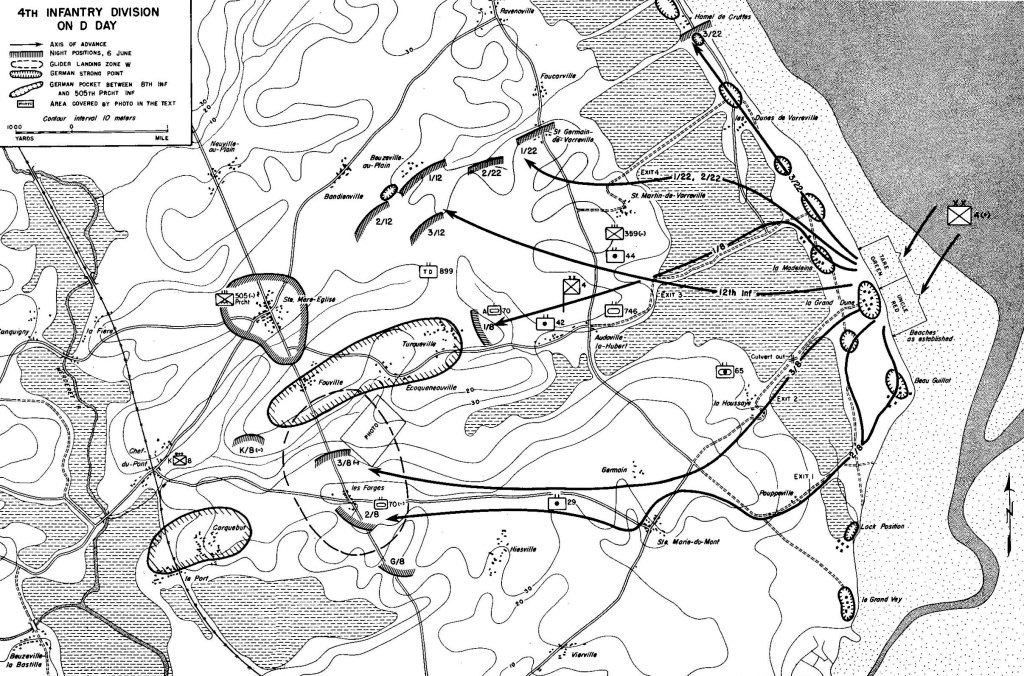

Crawford edged close to Capt. Robert Crisson, commander of C Company of the 8th Infantry Regiment, as the LCVP motored closer to the Normandy shoreline. Crisson had turned 23 less than two weeks earlier and was about to enter combat for the first time after five years in the Army. He reminded his men to take their time once they hit the water, as trying to run likely would only waste energy and slow their progress to the beach.

When the bow ramp finally dropped, Crawford “charged out with the rest trying to look fierce” and promptly stepped in a shell hole, briefly submerging him. But he popped up and struggled ashore, perplexed that the beach wasn’t being raked by machine-gun fire. He ran about 100 yards until he reached the concrete sea wall, where he hunkered down to collect himself and turned to survey the waterline. Crawford and the others in the first wave had had a relatively easy time of it.

"The soldiers were well out of the water, carrying packs, guns, heavy mortar parts, and radio equipment, by the time I made the beach," he would write later in Newsweek. "They crouched low and ran apelike. We had been told to expect booby traps and antipersonnel mines on the beach, machine-gun fire from the dunes, and probably artillery fire from behind them. Strangely, there were no mines and no machine guns. Only artillery fire, and that directed against the boats."

At some point in his observation of the frenzy of activity around him, Crawford glanced at his supposedly waterproof Helbros wristwatch, a gift from home delivered to him by Ernie Pyle in North Africa the previous Christmas. It had stopped shortly after 6:30 a.m.—H-Hour of D-Day for the 4th Infantry Division as the liberation of Europe began.

Ken Crawford was in the middle of the biggest story of his life. It was time to get to work.

He set about exploring the Tare Green sector of Utah Beach, now “swarming with men and vehicles.” Among those he encountered was the 4th's assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., who he identified only by title, not name, in his original dispatch. Roosevelt, huddled under a blanket at the seawall, handed Crawford one of his cigarettes, which he had kept dry during the landing by wrapping them in a condom, as the pair surveyed a nearby French village.

It was around this time that Roosevelt realized the first wave had been landed about a mile south of its intended beach. After conferring with his battalion commanders, the general decided to stay the course rather than diverting follow-on waves to their original target. Roosevelt turned to Col. Eugene Caffey of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, who had come ashore with Crawford, and made a call that features prominently in the film adaptation of Cornelius Ryan's seminal The Longest Day: "We're starting the war from right here."

By early evening, Crawford knew it was time to try and hitch a ride back to England. With press communications still an exceedingly low priority despite the stability of the beachhead, he understood the story he had gathered wouldn’t serve much purpose if he couldn’t get it out—a lesson plenty of other correspondents across the Cotentin Peninsula were to learn that day. Crawford talked a Navy beachmaster into putting him aboard a landing craft headed back to the USS Joseph T. Dickman, a 535-foot attack transport that had participated in Allied landings in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. As the casualty-laden ship steamed toward Portland on the south coast of England, Crawford warmed up with wardroom coffee and began to sort out the story he would eventually cable back to Newsweek’s offices for publication in the June 19 issue.

His account of the day, praised by peers and readers alike, is a masterpiece of observation, with the correspondent's own actions woven in and out of the narrative. His roommate in London, Richard Strout of the Christian Science Monitor, would describe it 40 years later as "what I think was the best eyewitness story of the day."

Early in the piece, he describes looking back toward the beach and seeing a German 88 shell burst among a group of seven men, killing all but one. "The seventh screamed in agonized amazement" and Crawford, seeing no medical corpsmen in that sector of the beach, ran to help him after the artillery fire abated. Shrapnel had broken the soldier's arm and leg, but Crawford was able to help the man to the sanctuary of the seawall. "Later I saw him aboard the evacuation barge," Crawford wrote. "He will have his arm and his leg, but they may not be much good."

Crawford describes engineers' blasts that "seemed big enough to demolish a skyscraper. Chunks of wall bounced off my helmet." A group of about 20 German prisoners who gave up willingly to the invaders "were mostly bedraggled teenagers, frightened and sometimes wounded in the terrific preinvasion bombardment from the sea and air."

We know now that the Utah landings went off much more smoothly, and with far fewer casualties, than those at "Bloody Omaha" and other beaches, and Crawford inferred the same at the time. He described how he and his shipmates "Monday-morning-quarterbacked the whole operation" on the ride back to England: "Veterans aboard agreed that no major amphibious undertaking they had ever seen or heard of had gone off nearly as planned in briefing rooms. The timing of artillery fire and the landings had been perfect. But for the perverseness of the elements, there hadn't been a hitch."

Before Crawford typed out those words upon his return to London, though, he had a more pressing dispatch to send. He composed a telegram to his wife, Elizabeth, in Harbor Beach, Michigan, and his enthusiasm jumped off the Western Union flimsy even in staccato cable-ese:

Of the hundreds of men and women who covered the long-awaited invasion of Europe, only a couple dozen or so actually set foot in France on June 6. Crawford's report from the day of days stands out in large part because of the access he was fortunate enough to secure, but access isn't worth nearly as much if you don't know what to do with it. This veteran correspondent knew exactly how to handle it, and it shows in the finished product.

Crawford had lost contact with Capt. Robert Crisson shortly after landing in France, but the correspondent made an impression on the young officer. He wrote to Crawford after the war of their trip to shore: “You were right beside me in the assault craft and on until we hit the beach. There of course—you had one job to do and I another.”