The Dambusters raid: Guy Gibson and 617 Squadron

Tonight, they are 617 Squadron. Tomorrow, the world will know them as ... The Dam Busters.

So intones the narrator on the trailer for the 1955 movie "The Dam Busters", a dramatized account of the Royal Air Force's ingenious attack on the dams of the Ruhr Valley in western Germany.

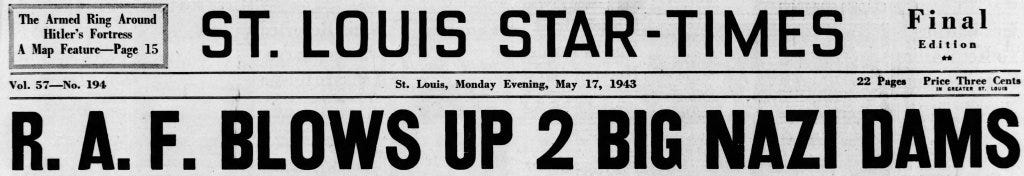

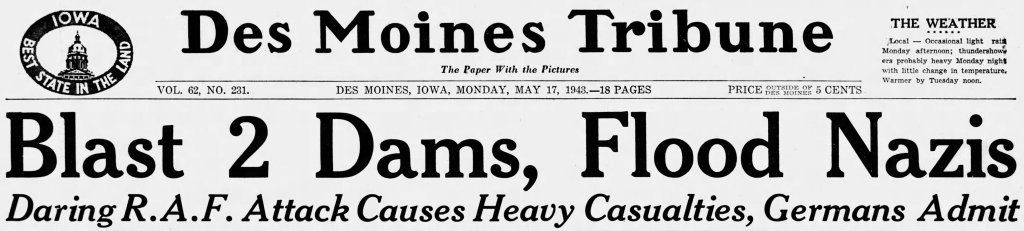

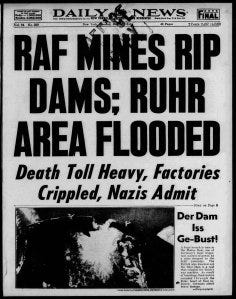

The actual raid took place the night of May 16-17, 1943, and news of the RAF's daring triumph did indeed capture the public's imagination in Britain and around the world.

British Air Minister Sir Archibald Sinclair broke the news in a speech during commemoration of Norwegian independence day at the Albert Hall, and subsequent communiques from the Air Ministry and German officials filled in some details. The press lapped it up, leading to banner headlines in evening newspapers in the UK and United States on the 17th and widespread coverage from the 18th on.

The Air Ministry announced two major dams, the Mohne and the Eder, had been breached by Lancaster bombers using aerial mines.

"The attacks were pressed home from very low level with great determination and coolness in the face of fierce resistance," a communique said.

The German communique was unusually honest, acknowledging "two dams were damaged and heavy casualties were caused among the civilian population by the resulting floods."

A 26-year-old United Press correspondent named Walter Cronkite led his dispatch from London with a more dramatic touch:

Billions of gallons of water thundered down two of Germany's greatest industrial valleys tonight, sweeping bridges and power plants before it and flooding vital Ruhr war production areas, as the result of an RAF raid last night in which two of the biggest dams in the Nazi Reich were broken.

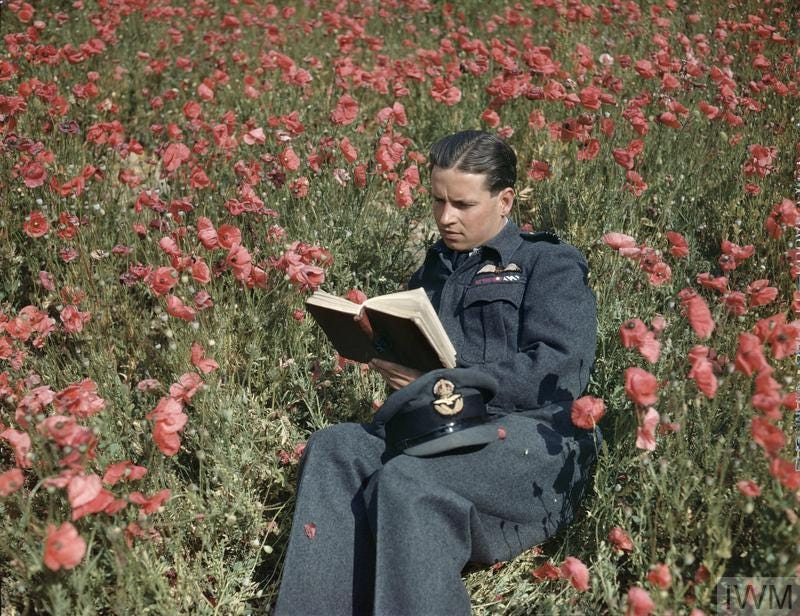

Initial reports included praise for the raid's leader, Wing Commander Guy Gibson, who would instantly become the hero du jour in Britain's war effort. Reports noted that Gibson, 24, had been described by superiors the previous month as having a "contempt for danger."

He described dropping the first mine at the Mohne dam, then flying up and down its length in an attempt to draw anti-aircraft fire away from the bombers behind him.

An unnamed Flight Lieutenant farther back in line described the scene this way in an account printed in multiple newspapers:

I was able to watch the whole process. The Wing Commander's load was placed just right and a spout of water went up 300 feet. A second Lancaster attacked with equal accuracy and there was still no sign of a breach. Then I went in and we caused a huge explosion up against the dam.

It was not until another load had been dropped that the dam at last broke. I saw the first jet very clearly in the moonlight.

Despite his youth, Gibson was an experienced bomber pilot who had proven his worth under fire -- including a year spent flying fighter planes. By the time of the Ruhr raid, he already had been decorated with the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, and the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar.

Gibson's work in the raid earned him Britain's highest military honor, the Victoria Cross. Word of the recognition from King George VI came down May 28, the day after Gibson and helped show the king and queen around RAF Scampton.

The Victoria Cross citation reads in part:

Both as an operational pilot and as leader of his squadron, he achieved outstandingly successful results and his personal courage knew no bounds. Berlin, Cologne, Danzig, Gdynia, Genoa, Le Creusot, Milan, Nuremberg and Stuttgart were among the targets he attacked by day and night.

The undertaking was officially known as Operation Chastise, but it soon acquired the nickname that would cement its place in history.

A Sydney Morning Herald editorial printed May 19 lauded the efforts of the RAF "Dambusters", a term that soon became the default label for 617 Squadron's work that night.

In mid-August, Guy Gibson traveled to Canada with Winston Churchill. He met with reporters in Quebec on Aug. 12, his 25th birthday, and was asked whether the prime minister called him by his first name.

"No, he usually calls me dambuster," Gibson responded.

He stayed in North America through the end of November, recounting the tale of the dams raid for reporters once again in New York in early October but mostly keeping a low profile throughout his tour before flying back home.

Gibson returned to combat action in early July 1944 and flew sporadically over the next several weeks.

On Sept. 19, he flew a Mosquito bomber in a raid over Mönchengladbach but didn't return, crashing on the way back at Steenbergen in the Netherlands.

Gibson was not officially listed as missing until Nov. 29, and his death was not announced until Jan. 8. He was buried in Steenbergen alongside Squadron Leader Jim Warwick, who shared the cockpit with him on their final flight.