Doug Werner's D-Day notebook

Merle McDougald Werner spent 15 years as a United Press correspondent, covering among many other stories the liberation of Paris, the occupation of Berlin and the Nuremberg trials. He then spent much of the Cold War as a foreign service officer in posts as wide-ranging as Austria, the Philippines and Pakistan and concluded his career with a 10-year stint at Voice of America.

Nothing he experienced across the decades, though, compared to June 6, 1944. Werner, who went by Doug but whose byline usually read Dougald, was one of the few correspondents to actually go ashore on D-Day.

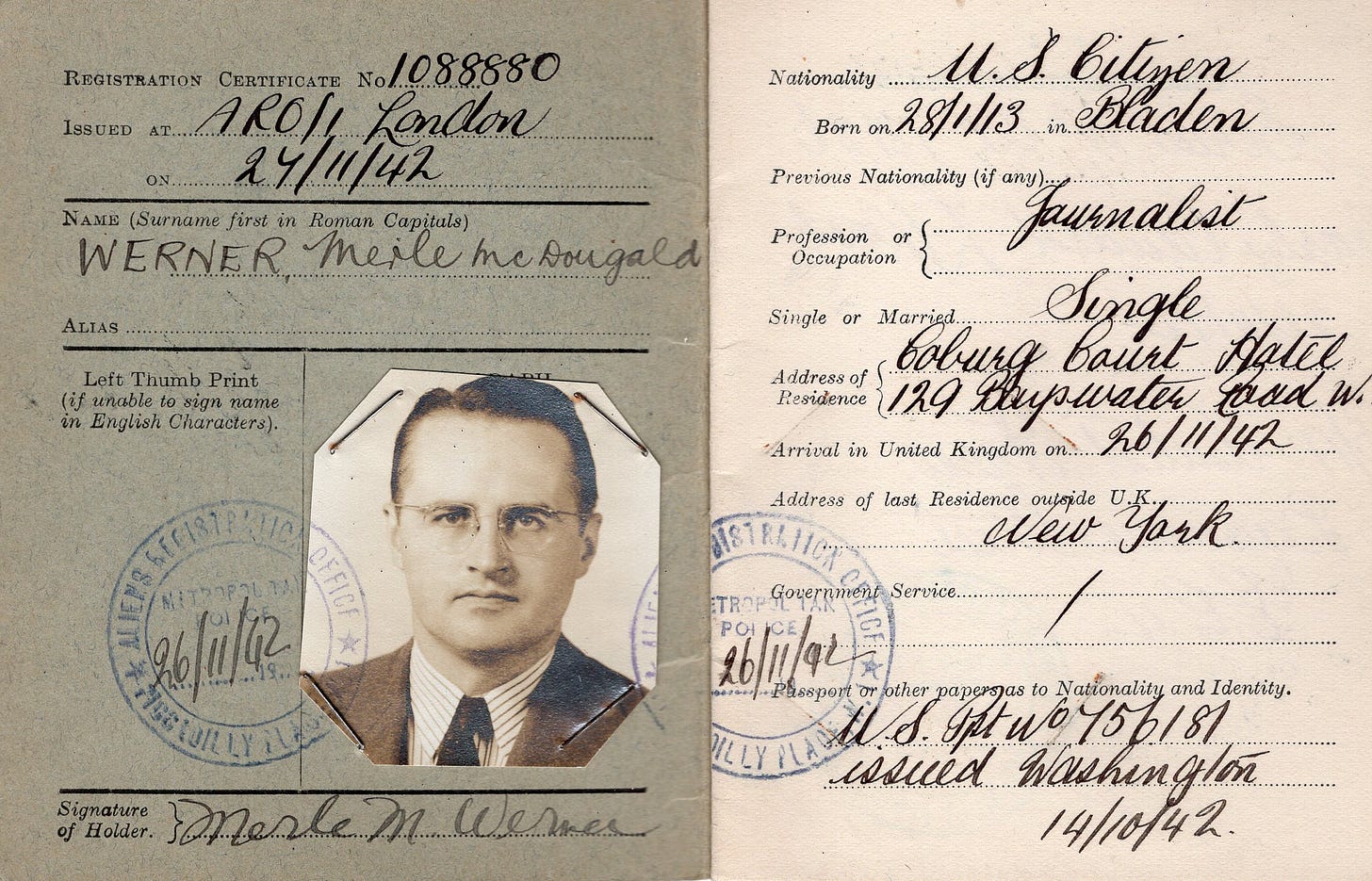

Born Jan. 28, 1913 in Bladen, Nebraska, Werner worked at several newspapers before joining the UP staff in 1937 in Des Moines. He moved on to Washington in 1941 and New York the following year before shipping out to Liverpool in November 1942.

He spent much of his time prior to Operation Overlord covering the air war from various bases in England before landing a coveted spot in the D-Day coverage plan. Werner was assigned to accompany the 819th Engineer Aviation Battalion onto Utah Beach, crossing the English Channel on LCT 580.

“Throughout the night we had watched as planes roared overhead and battleships took positions off the Normandy coast,” Werner would write of the experience 50 years later. “In the dark hours after midnight flares began to light up the sky — long strings of them drifting onto the Normandy countryside. It reminded me of the fireworks at the county fair back home in Nebraska, but such a peaceful image did not last long.”

Werner recorded his observations in a pocket-sized notebook with a red leather cover. Several years back, I was fortunate to be able to visit with his widow, Dorothy, and flip through that notebook and other items of memorabilia Werner had saved from his career.

Finally, nearly four hours after the first waves went ashore, it was Werner’s turn. He and his official escort, U.S. Army Capt. Haynes Thompson, hit the beach about four hours and 10 minutes after H-Hour.

We think of Utah as the “easier” of the two American invasion beaches, as opposed to “Bloody Omaha,” but no such thoughts ran through the men’s heads as they waded through four feet of water to reach the Uncle Red sector of the sand.

I learned quickly the art of diving into the nearest foxhole. When there wasn’t a foxhole handy I found myself down on my stomach digging one with my hands and feet. The shells would come over one after another and then there would be a pause and we would stick our heads out of the sand and crouch-run to another foxhole. …

We spent nearly an hour moving down a stretch of sand less than a mile long but it was an hour of horror — and in some cases, incredible bravery. Two of our young GIs were near a trailer when mortar shells hit it and set it afire. They quickly climbed onto a truck, got an extinguisher and put out the blaze just before it reached a store of ammunition. The young medics who treated the wounded were calm and cool under fire. We watched as they assisted two badly wounded German soldiers. By contrast, the next day as we moved inland, we saw the bodies of four German soldiers, two of them with their throats cut. …

Before nightfall, Tommy and I dug a foxhole under a hedgerow along a road near the strip. We had no blankets or covering and we slept fitfully in our wet clothes and boots. We were cold, but we weren’t complaining because we were alive and there were no more German shells bursting near us. I opened my portable typewriter and started typing out my description of the day. That dispatch from the beach was taken back to London the next morning by courier and circulated to newspapers throughout the states by the United Press.

Werner’s story wasn’t as widely circulated as many of his colleagues’ — perhaps because of delays in getting through the unwieldy communication and censorship apparatus.

In fact, the UP tacked much of his original D-Day dispatch onto the end of another story he filed from Normandy two days later, a version that ran in many U.S. papers on June 10.

Regardless of the impact his initial reports from the invasion had back home, Werner took pride in the experience the rest of his life, referring to D-Day 50 years later as “the high point in the modern history of our country.”

“Now I realize how lucky I was,” he wrote. “Lucky to have participated in covering the biggest news story of my generation and most of all, lucky to have lived through it.”