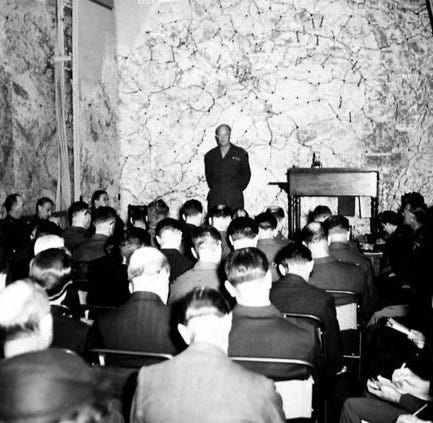

Eisenhower meets the press in London

When we look back at Dwight D. Eisenhower now, knowing what he did and who he became, we can sometimes lose sight of the fact that none of the history we know was a given at the time.

Eisenhower was a somewhat unconventional choice for the roles U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall elevated him to -- first in North Africa and then leading the critically important invasion of Northwest Europe. But Marshall knew what everyone else would soon learn: though Eisenhower had minimal battlefield experience, he was a master diplomat whose interpersonal skills were perfectly suited to his job as leader of multinational coalition bristling with massive egos.

Not least among those varied constituencies was the press, and Eisenhower quickly established a respectful rapport with journalists that would serve him well throughout the war. His handling of the controversy around the Patton slapping incidents in 1943 was a prime example of Eisenhower's skill in leading the media where he wanted them to go without the relationship becoming antagonistic.

When Eisenhower was named Supreme Allied Commander for the pending invasion, the stakes got even higher. The 53-year-old was the public face of the war effort in Europe, and he knew he would need the press to help shape the messaging around the latter stages of the war.

His effort began at 11 a.m. on Monday, Jan. 17, 1944. That morning, about 50 correspondents gathered at 20 Grosvenor Square in London for Eisenhower's first press conference since leaving the Mediterranean to devote his full attention to preparations for the invasion.

Speaking from his desk, which was flanked by British and American flags and portraits of Churchill and Roosevelt, Eisenhower made it clear from the beginning that his session would not fill up broadcasts or newspaper columns that day -- "I haven't any startling announcements to make that will make any headlines," he told them. Instead, he framed the meeting as a getting-to-know-you exercise in which he would lay out some of his press-relations philosophies and share some of his big-picture thoughts on the war situation.

In fact, one announcement Eisenhower made that day did generate worldwide headlines and became the thrust of every news story written off the press conference: the answer to the first question Eisenhower fielded from the correspondents after he had said his piece. In response to a query about who would be British Gen. Bernard Montgomery's "opposite number" on the U.S. side, Eisenhower released the news that Gen. Omar Bradley would be the senior American ground commander in the European theater -- though he cautioned the correspondents against indicating that the two generals' roles would be equal.

Bradley's appointment led the wire service stories by Lewis Hawkins of the Associated Press and his United Press counterpart Edward Beattie. Drew Middleton did the same in The New York Times, devoting most of his front-page story to Bradley's back story and qualifications for the position but also taking a paragraph to highlight Eisenhower's constant messaging around Allied unity:

It was notable that in his praise General Eisenhower not once identified the forces as "American" or "British" but simply as the air forces or navies or infantry, a continuation of his "Allied viewpoint" so evident in the Mediterranean campaign. "I am an Allied commander," he said, emphasizing "Allied."

Incidentally, the Bradley news that dominated the stories written that day was apparently news to its subject as well. In his 1951 memoir A Soldier's Story, Bradley wrote that he stopped to pick up a copy of the Daily Express on his way out of the Dorchester Hotel the following morning and was stunned to find himself mentioned on the front page.

"This was the first inkling I had that my Army Group command was to be more than a temporary one," Bradley wrote. "Eisenhower had just arrived in England and I had not yet talked with him."

Of all the correspondents on hand, Thomas M. O'Neill of the Baltimore Sun was one of the few who led with the public relations angle; his story for the Jan. 18 morning editions didn't mention the Bradley news until the eighth paragraph. Instead, O'Neill focused on Eisenhower's message to the press:

He told them, mincing no words, what would be expected from them in the interest of security for Allied fighting men. He told them, too, just as abruptly, what they could expect from him in the way of making war news available in maximum quantities and at maximum speeds, commensurable with the protection of the men on the fighting lines from unintended hints to the enemy.

Eisenhower pulls no more punches when talking than when fighting. He made it clear that his fundamental philosophy accepts anybody who is not for him as against him. It was also apparent that he would rather have you with him than against him, and that it will be so if a fair attitude on his part will bring this about.

"Basically and fundamentally," he said, "public opinion wins wars."

Lower in the story, O'Neill referenced a nugget that also appeared in other outlets: Eisenhower's unusual tactic of informing correspondents attached to his headquarters in North Africa a month in advance about the upcoming invasion of Sicily, "thus successfully insuring against the premature publication of facts foretelling the landing which correspondents had observed independently."

Alas, there was no such early notification handed down on this day. "The general showed no inclination to confide the date of the European invasion," the London correspondent for The Guardian lamented.

Nonetheless, the anecdote managed to convey Eisenhower's cool-headed control of his realm and signal to the readership -- not to mention other powerful officials -- that the press could be trusted.

Shot through it all was Eisenhower's decision to frame the relationship as a give-and-take, a construct he returned to repeatedly in his remarks that day. Though only a few snippets of his comments ended up in the newspapers, a transcript in the SHAEF files shows how hard the general drove that message home.

The point I am trying to get at is this: I will not tolerate in my theater an atmosphere of antagonism between myself and the newspaper people where I am on one side of the fence and you are on the other. I take it you are just as anxious to win this war and get it done so we can all go fishing as I am, and as long as any correspondent adopts that attitude and continues to operate along those lines, he will find no difficulty with me. ...

I am not concerned about an error that one of you may make, and I hope you are not going to be too concerned about some error I may make, as long as it isn't far-reaching in its results. As digression right there, there is one thing that will never be censored in my headquarters -- any criticism you have to make of me. That will never be censored, you can be sure.

But on the other hand, and to go back to my original theme, we are partners in a great job of defeating the Axis. You have got your job, and I have mine. I think if we can adopt and live by that program we'll have very little trouble.

It's not that Eisenhower managed to navigate the war in the Mediterranean and Europe with no headaches from the press, but his approached undoubtedly smoothed the way for him at times in that all-important court of public opinion.

He projected calm, authority, humility and intelligence, and the correspondents passed those favorable impressions along to their readers and listeners. As O'Neill wrote at the end of his piece for the Sun:

There was nothing in the attitude of the 53-year-old Eisenhower to suggest the crushing responsibilities that have been entrusted to him. He is agile, interested and interesting. Every question got an answer; though, as formerly, he was chary of quotation.

He doesn't care for talking generals. He believes that military commanders are hired for purposes other than speechmaking.