Murrow at Buchenwald: 'I pray you to believe what I have said'

Permit me to tell you what you would have seen, and heard, had you been with me on Thursday. It will not be pleasant listening. If you are at lunch, or if you have no appetite to hear what Germans have done, now is a good time to switch off the radio, for I propose to tell you of Buchenwald.

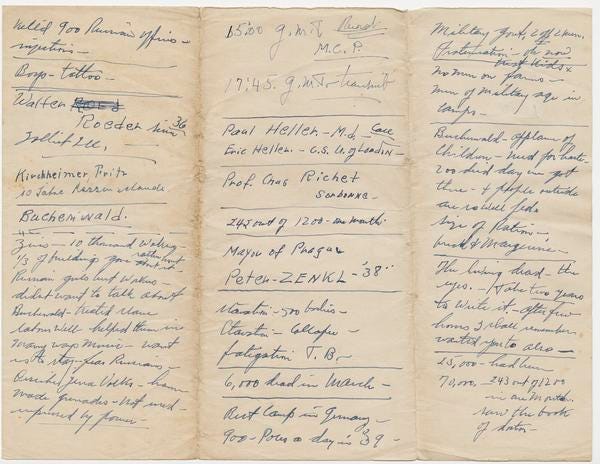

Edward R. Murrow spoke those words into the CBS microphone on Sunday, April 15, 1945, preparing the listener for perhaps his most devastating wartime broadcast.

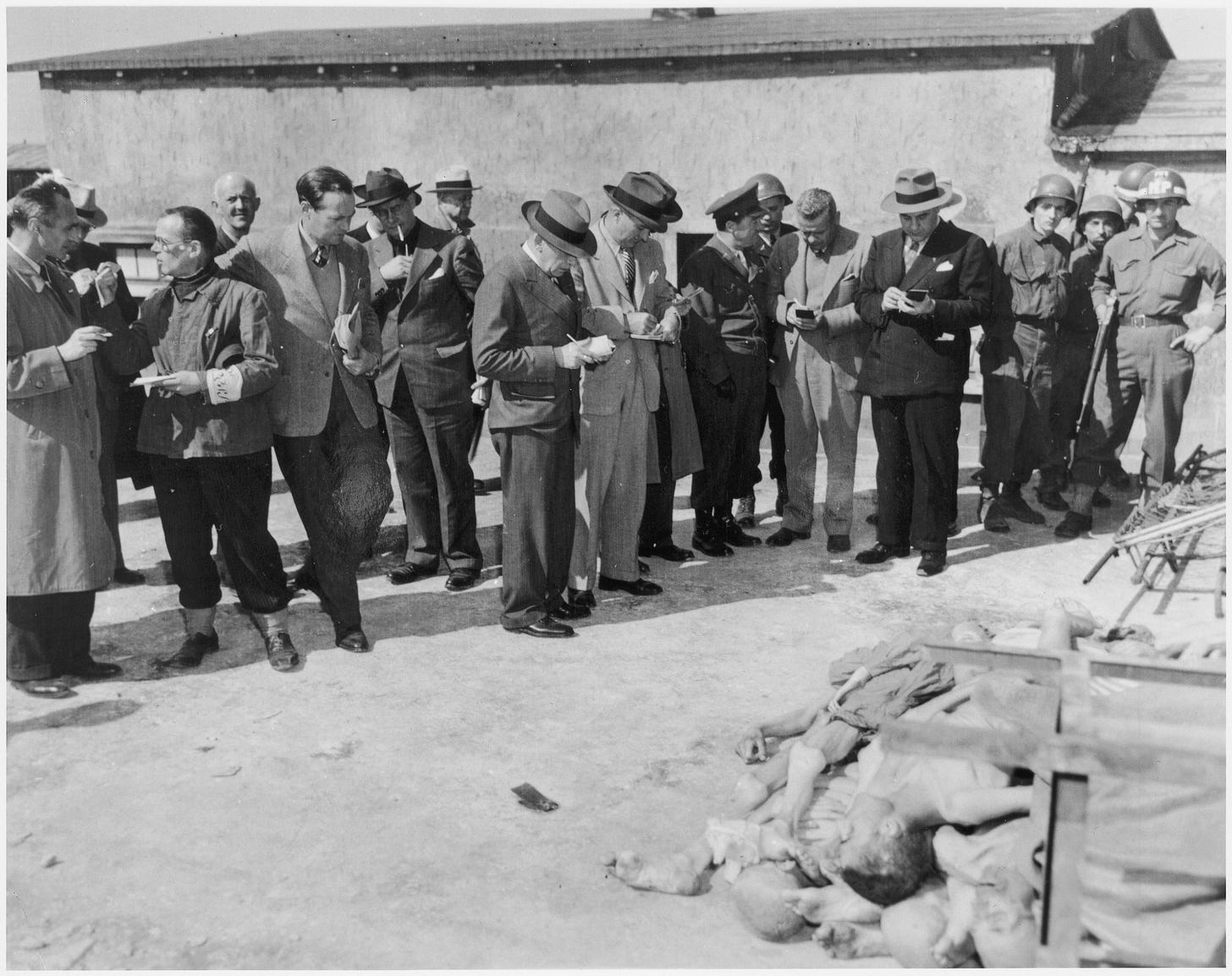

Murrow visited the camp on April 12, a day after elements of the U.S. Third Army had liberated it. Over the next two weeks, the site became the centerpiece in an Allied public relations effort; a place to bear witness to the unfathomable reality few had wanted to acknowledge.

Buchenwald’s existence was no secret. It was first mentioned in British and American newspaper reports in 1938, and in February 1939 the Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle ran a lengthy piece by Jewish Telegraph Agency correspondent Norris Wood detailing some of the indignities being perpetrated at Buchenwald, Dachau and Sachenhausen in the years before they truly became death factories. It ran under the headline “Laboratories of Hatred”.

While that summary would have been an accurate description of what witnesses would discover at Buchenwald six years later, it would not have been adequate.

International News Service correspondent Pierre J. Huss described the compound near Weimar as “a grisly monument to the Nazis’ efficiency to murder.” The tableau presented a challenge to the journalists on the scene: What combination of words could possibly describe what lay before them?

Stringing together a series of vignettes, Murrow managed as well as any of his colleagues. He began his observations with an apology for using the first person, “for I was the least important person there, as you shall hear.”

Early in his account, he stepped into a barracks filled with Czechoslovakians:

When I entered, men crowded around, tried to lift me to their shoulders. They were too weak. Many of them could not get out of bed. I was told that this building had once stabled eighty horses. There were twelve hundred men in it, five to a bunk. The stink was beyond all description.

When I reached the center of the barracks, a man came up and said, “You remember me. I’m Peter Zenkl, one-time mayor of Prague.” I remembered him, but did not recognize him.

From there, Murrow ratcheted up the horror.

As we walked out into the courtyard, a man fell dead. Two others — they must have been over sixty — were crawling toward the latrine. I saw it but will not describe it.

His escorts directed him to a small courtyard bordered by a wall about eight feet high.

It adjoined what had been a stable or garage. We entered. It was floored with concrete. There were two rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood. They were thin and very white. Some of the bodies were terribly bruised, though there seemed to be little flesh to bruise. Some had been shot through the head, but they bled but little. All except two were naked. I tried to count them as best I could and arrived at the conclusion that all that was mortal of more than five hundred men and boys lay there in two neat piles. …

It appeared that most of the men and boys had died of starvation; they had not been executed. But the manner of death seemed unimportant. Murder had been done at Buchenwald.

Murrow would learn on the evening of the day he visited the camp that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died. He closed his broadcast by noting how “many men in many tongues blessed the name of Roosevelt” in greeting their American liberators, hours before the president’s death.

But before he got there, he preemptively addressed any skepticism that might greet his report.

I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. Dead men are plentiful in war, but the living dead, more than twenty thousand of them in one camp …

If I’ve offended you by this rather mild account of Buchenwald, I’m not in the least sorry.

Murrow’s dispatch made waves on both sides of the Atlantic. In the U.S., The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich author William L. Shirer described it in his syndicated column as “one of the most heart-rending broadcasts I’ve ever heard.” Two days after the report, the London correspondent for The Nottingham Journal wrote that it “affected public opinion in London more deeply than anything of the kind that has been revealed by the recession of the German tide.”

While Murrow’s account may have made the widest initial impact, Allied officials were intent on reinforcing his and others’ reporting. At Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s request, they arranged for a Congressional delegation led by Rep. Clare Boothe Luce of Connecticut to tour the site on April 21, coincidentally the same day 10 members of the British Parliament visited the camp.

Other senators and congressmen would follow, as would a group of 17 American newspaper and magazine editors and publishers. They toured other liberated camps as well, but many made Buchenwald the focus of their dispatches.

“There is no need of going into details. They have all been told,” wrote Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler from Paris on April 27. “My purpose is merely to testify as to the accuracy of the American correspondents — they have told the truth. They have not exaggerated. Exaggeration, in fact, would be difficult.”

Joseph Pulitzer echoed that point in his St. Louis Post-Dispatch, acknowledging that he had arrived for the tour “in a suspicious frame of mind” about the extent of the depravity, believing initial accounts might have been inflated for propaganda purposes.

“It is my grim duty to report that the descriptions of the horrors of this camp, one of many which have been and which will be uncovered by the Allied armies, have given less than the whole truth,” Pulitzer wrote. “They have been understatements. The brutal fiendishness of these operations defies description.”

Cementing that reality in the minds of skeptics like Pulitzer was of course the point of the publicity effort, and the preponderance of evidence from Buchenwald and other liberated camps laid the groundwork for more comprehensive accounts of the atrocities carried out there.

As for Murrow and the others who had witnessed Buchenwald firsthand in April of 1945, though, they had seen enough. The broadcaster’s CBS colleague Charles Collingwood was also there that day, and he told Murrow’s biographer A.M. Sperber decades later of the impact the visit had on his friend:

“Those scenes … they remained with Ed and haunted him. It was something which affected him, I would guess, for the rest of his life.”

Listen to Murrow’s full Buchenwald broadcast here: