'Orchestrated Hell': Edward R. Murrow over Berlin

Last night, some of the young gentlemen of the RAF took me to Berlin.

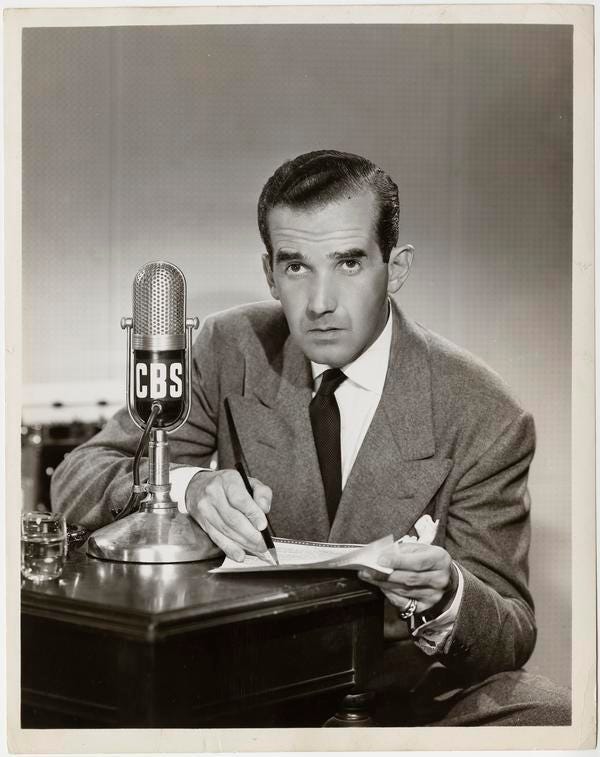

Edward R. Murrow was nothing if not cool, as the opening sentence of perhaps his most famous wartime report makes clear. Seated before a microphone at the BBC's London studios on December 3, 1943, Murrow spent 18 minutes walking CBS listeners through his experience accompanying a bombing raid over Germany's capital the previous evening.

The broadcast is loaded with the immediacy and vivid imagery that had established Murrow as America's premier broadcast correspondent during the Blitz more than three years earlier, but its overall tone stands out as well. While Murrow's descriptions of the British aircrew's grace under fire certainly fits the stereotypical businesslike, stiff-upper-lip image of our men at war, there is no cheerleading and only a bare minimum of triumphalism here. It's a portrait of men doing a dirty job -- the same kind of work they did yesterday and, if they're fortunate enough to return, will do again tomorrow.

Murrow's biographers estimate he flew on about 25 combat missions throughout the war, to the increasing annoyance of his bosses at CBS. The danger was self-evident; earlier in 1943, New York Times correspondent Robert P. Post had been killed while accompanying the U.S. Eighth Air Force on a raid to Wilhelmshaven, Germany. There would be noncombatant casualties on this December run to Berlin as well.

Still, Murrow felt it was his duty to take on assignments like this in service of the larger story. In his view, "no one was indispensable; no one was that important," as Ann M. Sperber wrote in her 1986 biography, Murrow: His Life and Times.

So it was that the 35-year-old correspondent found himself clambering aboard the RAF Lancaster bomber "D for Dog" the night of December 2.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3FY0KFqmURM

As they headed out over the North Sea with pilot Jock Abercrombie at the controls, "Everyone sounded relaxed. For a while, the eight of us in our little world in exile moved over the sea."

Over the next couple minutes of the broadcast, Murrow runs through mentions of the other crew members -- Jack, the tail gunner; Wally, the mid-upper gunner; Dave, the navigator. Nervous anticipation builds before Murrow gets to the first indications of the battle to come, in the form of flak bursting in the sky and searchlights cutting through the night about 30 miles out from Berlin.

And then, with no warning at all, D-Dog was filled with an unhealthy white light. I was standing just behind Jock and could see all the seams on the wings. His quiet Scots voice beat into my ears, "Steady lads, we've been coned." His slender body lifted half out of the seat as he jammed the control column forward and to the left. We were going down.

Jock was wearing woolen gloves with the fingers cut off. I could see his fingernails turn white as he gripped the wheel. And then I was on my knees, flat on the deck, for he had whipped the Dog back into a climbing turn. The knees should have been strong enough to support me, but they weren't, and the stomach seemed in some danger of letting me down, too.

I picked myself up and looked out again. It seemed that one big searchlight, instead of being 20,000 feet below, was mounted right on our wingtip. D-Dog was corkscrewing. As we rolled down on the other side, I began to see what was happening to Berlin.

The clouds were gone, and the sticks of incendiaries from the preceding waves made the place look like a badly laid-out city with the streetlights on. The small incendiaries were going down like a fistful of white rice thrown on a piece of black velvet. As Jock hauled the Dog up again, I was thrown to the other side of the cockpit.

Murrow says flatly that he was "very frightened" as he contemplated the notion of D-Dog navigating the maelstrom with those incendiaries and a 4,000-pound high-explosive "cookie" still on board. The narrative then turns to the bomb run itself, led by Buzz the bombardier. After a near-collision with a fellow Lancaster, the crew turned back toward England.

I looked on the port beam at the target area. There was a red, sullen, obscene glare. The fires seemed to have found each other and we were heading home.

They weren't free and clear yet, though -- D-Dog had to navigate back through the same flak fields it had on the way in.

And a great orange blob of flak smacked up straight in front of us and Jock said, "I think they're shooting at us." I'd thought so for some time. ...

When we were clear of the barrage, I asked him how close the bursts were and he said, "Not very close. When they're really near you can smell 'em." That proved nothing for I'd been holding my breath.

That proved to be the last of the resistance the Lancaster encountered on its way home. Eventually they crossed back over the North Sea and found themselves over England, where they were diverted to land at the RAF airfield at Coningsby in Lincolnshire, about 130 miles north of central London.

Nearing the end of his report, Murrow mentions the too-close-to-home news that has already been out on the wires and in newspapers: Two fellow correspondents accompanying the raid didn't make it back.

Australian Norman Stockton of the Sydney Sun and American Lowell Bennett of the International News Service were in Lancasters that were shot down during the raid. Stockton was killed, but Bennett survived and was eventually liberated from Stalag Luft I by Soviet troops on April 30, 1945.

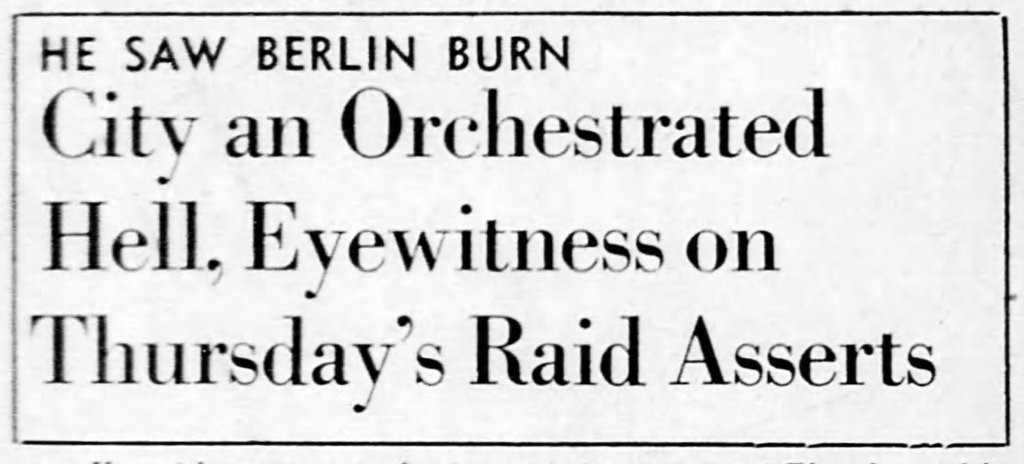

Bennett had been slated to serve as the pool reporter on the raid for U.S. news services, with his report to go out via INS as well as the United Press and the Associated Press. As Murrow noted in his broadcast, tradition held that survivors step in for any colleagues who were "prevented by circumstances from filing their stories," so a pared-down version of his account went out on the wires in lieu of a dispatch from Bennett.

It received prominent play in newspapers throughout the U.S., with many headline writers seizing on the phrase that punctuated Murrow's radio report.

Here, Murrow's original conclusion in full:

Berlin was a kind of orchestrated hell -- a terrible symphony of light and flame.

It isn't a pleasant kind of warfare. The men doing it speak of it as a job. Yesterday afternoon, when the tapes were stretched out on the big map all the way to Berlin and back again, a young pilot with old eyes said to me, "I see we're working again tonight." That's the frame of mind in which the job is done.

The job isn't pleasant -- it's terribly tiring. Men die in the sky while others are roasted alive in their cellars. Berlin last night wasn't a pretty sight. In about 35 minutes it was hit with about three times the amount of stuff that ever came down on London in a night-long blitz. This is a calculated, remorseless campaign of destruction. Right now the mechanics are probably working on D-Dog, getting him ready to fly again.

I return you now to CBS New York.

Murrow's broadcast instantly took a prominent place among the great pieces of reportage from the war, a distinction that hasn't faded in three quarters of a century since.

CBS colleague Charles Collingwood, who was in New York at the time, wrote Murrow praising the report -- and mocking CBS news director Paul White's concerns about the risks Murrow was taking. Authors Stanley Cloud and Lynne Olson quoted from the note in their book The Murrow Boys:

"That was a great piece you did on the Berlin raid," Collingwood wrote. "... White was very upset before the show. Said you were crazy to have gone and all the rest of it. Swore that besides all the risk it was impossible to make a good story out of it. I told him that you had to go and that having gone it would be impossible for you to write a bad story about it. ... After it was over I made the bastard buy me a drink as recompense for having been so stupid."

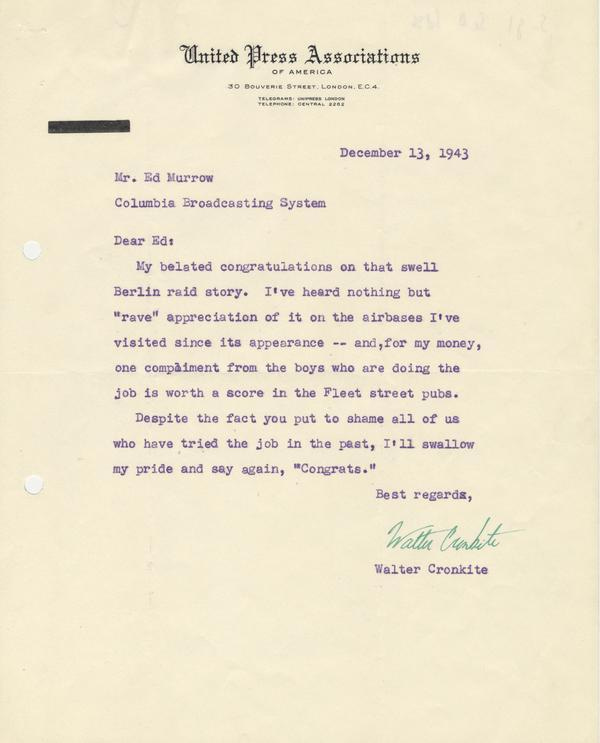

Murrow also heard from Walter Cronkite, a veteran of bomber coverage whose account of the Wilhelmshaven raid for the United Press had marked him as a star. From the Murrow papers at Mount Holyoke College:

It wasn't just Murrow's fellow correspondents who instantly recognized the report's greatness, either. Radio columnist Ben Gross of the New York Daily News summed it up nicely with a blurb in his December 4 column, calling it "an unforgettable piece of radio reporting." He continued:

I have read many descriptions of what it is like to be flying through searchlights, flak and ferocious fighters over enemy territory. But this was the best of them all. It was so vivid that every listener must have regarded it not merely as a great story well told, but as a searing experience through which he himself had lived.