Edward R. Murrow, the voice of the war in Europe

For millions of Americans, Edward R. Murrow’s voice was the definitive sound of wartime news.

From the beginning of World War II in 1939, the authoritative baritone announcing “This is London” cued listeners for another report from the man who changed the way news was broadcast in the U.S. From his work building the news operation at CBS to his pioneering on-the-spot reports from the front, Murrow established his legacy as one of the great broadcast journalists in history during the war years.

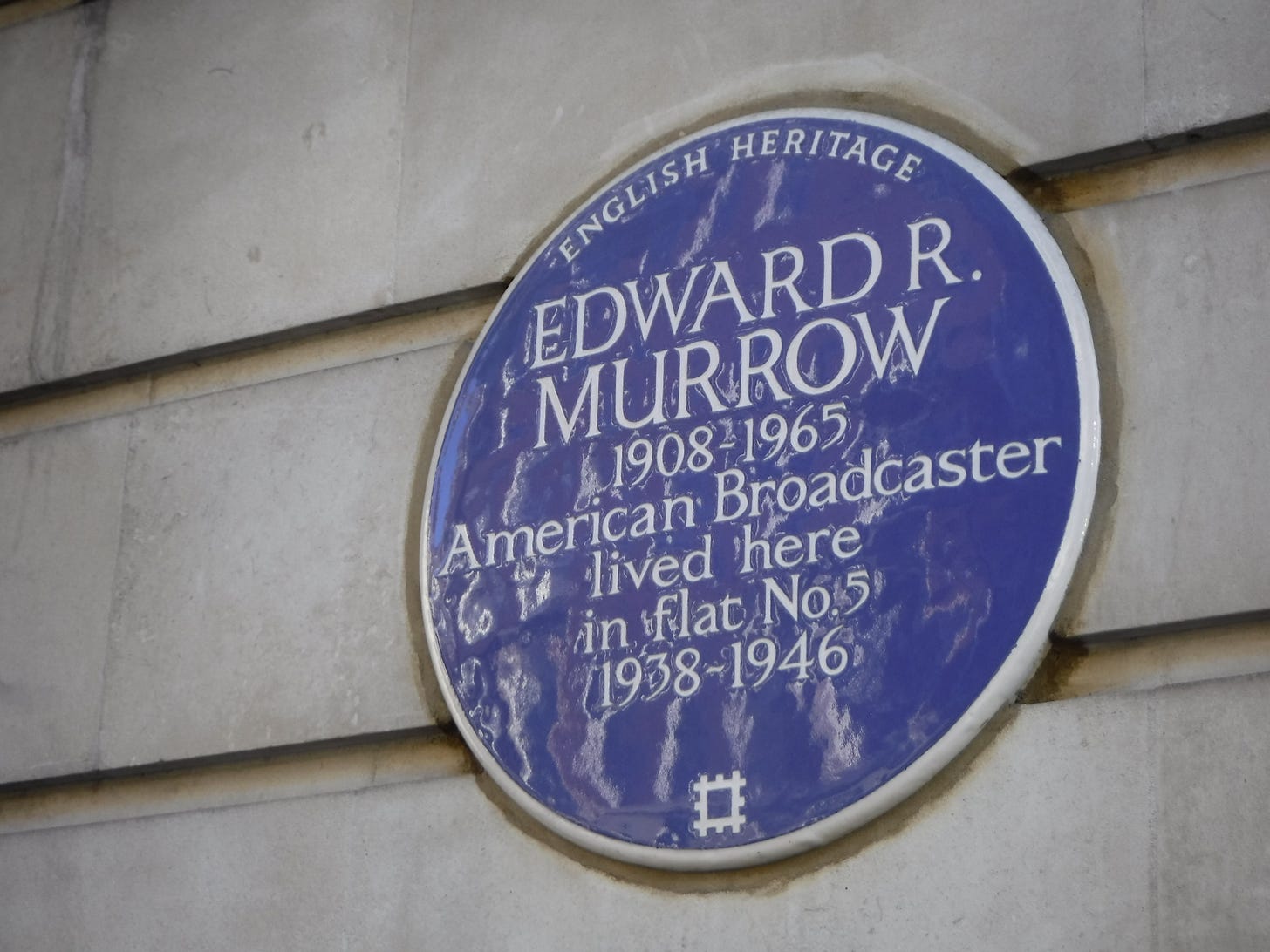

Born Egbert Roscoe Murrow on April 25, 1908 in rural Guilford County, North Carolina, the man who would legally change his name to Edward some 20 years later spent most of his formative years in Washington state, attending high school and college there.

He joined CBS in New York in 1935 and went to London two years later as the network’s European Director of Talks. Broadcast news at the time consisted only of an announcer in a studio reading updates, but Murrow would lead the drive toward actual journalism, hiring a devoted network of correspondents who would become known as the Murrow Boys.

The first of the group was the newspaper correspondent William L. Shirer, who was in Vienna when Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938. Murrow had Shirer fly back to London and give his report on the air, the first foreign news broadcast in CBS history.

Shirer had no radio training, and in that he set the mold for most of the rest of the Murrow Boys. “I’m hiring reporters, not announcers,” Murrow said more than once in response to any complaints about their broadcast technique.

Despite his natural gifts at the microphone, it’s worth remembering that Murrow was sent to London in an administrative role. But he really came into his own when he began to go on the air more regularly, particularly in his approach to covering the Blitz in 1940. Not content to offer up descriptions and run down damage reports from the studio, he broadcast from rooftops in the midst of German air raids.

In a 1953 New Yorker profile of Murrow, an unnamed CBS colleague offered this assessment: “In some way that I don’t pretend to understand, Ed’s all wound up and can’t slow down. I think that, like a lot of other people, he hit his high spot emotionally during the war—specifically, in his case, during the Battle of Britain, when he was living in the midst of disaster, and that sepulchral ‘This is London’ of his was the voice of England telling America about it.”

Many credit the reports he made during the bombings with building American sympathy for the British cause, helping pave the way for Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy” notion and eventually Lend-Lease even as the U.S. remained officially neutral in the war.

Though he remained based in London throughout the war, Murrow headed to the scene of the action whenever he could over the next five years. Whether riding along on a bombing raid of Berlin or witnessing the atrocities that had occurred at Buchenwald, he craved a firsthand look at what was actually happening.

While he may have thrived professionally in the wartime environment, Murrow had no illusions about the cost. On the day Japan’s representatives signed the surrender documents in Tokyo Bay, Murrow began his broadcast from London this way:

And now there is peace. The papers have been signed. The last enemy has given up — unconditionally. There is a silence you can almost hear. Not even the distant echo of guns or the rumble of bombers going out with a belly full of bombs, no more crisp or circuitous communiques. There are white crosses, and scrap iron, scattered round the world, and already some of the place names that will appear in the history books are fading from memory. (They will remain realy only to those who were there.) Six years is a long time — and it was more than twice as long for the Chinese.

Today is so much like that Sunday six years ago today. There is sun; the streets are empty. There is just enough breeze to fill the sails of small boats on the Thames. People are sitting in deck chairs in the parks. People and chairs are shabbier than they were six years ago. It is a long time, long enough for nations to disappear and be recreated. Long enough for the whole moral and material complexion of a continent to be altered, for cities that were a thousand years in the building to be destroyed in a night, long enough for a way to be found that may destroy humanity.

That reference to the atomic bomb and remarks later in his report pointing to seeds of the coming Cold War that already had been sown lent a downcast note to a historic day. Perhaps Murrow had just seen too much to have confidence the world would figure things out.

Given all he had witnessed over the past decade, he can be forgiven for that one last dose of realism offered up in assessing a global calamity.