Ernest Hemingway invades London ahead of D-Day

Gertrude Lawrence had been trying for some time to get back home after spending years in the United States. The actress finally secured a seat from New York to London on the Pan-Am Clipper in mid-May 1944 but worried to a fellow passenger right up until takeoff that she might get bumped from the flight.

"If I lose this seat because of a late priority, I'm going to hide in your beard all the way across," she told Ernest Hemingway, according to a New York Daily News account.

Thankfully for all involved, no such measures were necessary. The actress and the author made it across the Atlantic with no issues, though Hemingway would make plenty of waves upon arrival.

The 44-year-old had mostly spent the Second World War on the sidelines, but was now determined to insert himself into what promised to be the conflict's biggest story: the inevitable Allied invasion of Northwest Europe. So determined that he had secured himself passage on the Clipper while leaving his wife and fellow Collier's correspondent Martha Gellhorn to make the Atlantic crossing via ship ... a ship loaded with dynamite.

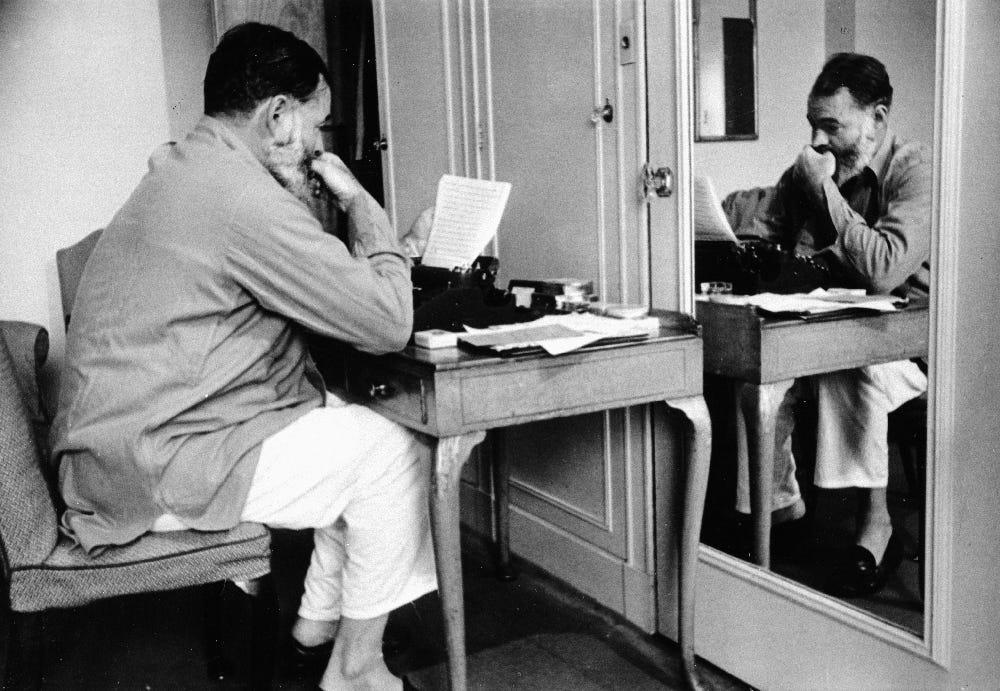

Hemingway had never set foot in London before but soon acclimated himself to the bustling center of activity, checking into the Dorchester Hotel and renewing acquaintances with his media and military pals.

His presence around town was gossip column-worthy, and nearly every published reference to him upon arrival in England commented on his prodigious salt-and-pepper beard, as Lawrence had.

Speaking of gossip columns, someone had planted a seed with Leonard Lyons back home. His column published May 24 in many U.S. newspapers included a once-sentence item of interest: "Ernest Hemingway, who arrived in England last week, will be allowed to accompany the first assault wave in the invasion."

This was wishful thinking by all involved, but such bravura suited his hard-charging persona, cultivated with tales from the Great War and the Spanish Civil War.

That same day, the 24th, one of Hemingway's pals from the glory days in Spain threw a party in the writer's honor at his London flat. Robert Capa rounded up an impressive cache of liquor for the occasion: 10 bottles of Scotch, eight bottles of gin, a case of champagne and some brandy, according to the photographer's autobiography.

The attraction of free booze combined with Mr. Hemingway proved irresistible. Everyone was in London for the invasion, and they all showed up at the party.

(Among the guests was Bill Walton, the Time and Life correspondent who two weeks later would have the kind of combat reporting experience Hemingway thrived on, parachuting into Normandy with the 82nd Airborne early on June 6.)

The festivities broke up sometime after 4 a.m. on the 25th, with Dr. Peter Gorer and his wife offering to give Hemingway a lift back to the Dorchester. Driving through the blacked-out streets on the way from Belgrave Square to Park Lane, Gorer plowed into a water tank that had been stationed in the road at Lowndes Square.

Hemingway got the worst of it, suffering serious cuts to his head and a concussion. He was taken to St. George's Hospital at Hyde Park Corner (the building is now a luxury hotel, The Lanesborough) where he underwent what initial reports called a "minor operation."

All of the wire services moved articles on the wreck, with varying degrees of accuracy. The International News Service version said Hemingway was driving, and had been "badly injured in the head and face." The Associated Press and United Press correctly said he was a passenger in the car, with the AP citing authorities saying the author was "in no apparent danger."

A follow-up AP report the following day said Hemingway had been transferred from the hospital to the London Clinic and was reported to be in "satisfactory" condition.

His injuries called into question whether he would be able to cover the invasion he had crossed the Atlantic to witness, but Hemingway managed to keep himself in the mix. He was discharged May 29, just in time to get the call from SHAEF public relations days later that summoned correspondents for their D-Day assignments.

Hemingway sailed from Portland aboard the transport Dorothea L. Dix, then transferred to the Empire Anvil and finally an LCVP off Omaha Beach. His account printed in the July 22, 1944 edition of Collier's, headlined "Voyage to Victory", begins there.

In this telling, Hemingway is intimately involved in the action, giving navigational guidance to the crew as it struggles to find the Fox Green sector of Omaha.

"This has got to be Fox Green," I said to Andy. "I recognize where the cliff stops. That's all Fox Green to the right. There is the Colleville church. There's the house on the beach. There's the Ruquet Valley on Easy Red to the right. This is Fox Green absolutely."

"We'll check when we get in closer," Andy said. "You really think it's Fox Green?"

"It has to be."

Hemingway maintains this role throughout the piece, positioning himself as a key cog in the LCVP's actions as they all try to piece together what's happening off Omaha. Hemingway's craft was in the seventh wave to hit the beach, likely around 7:35 a.m. -- an hour after the first troops went ashore.

The writer himself wouldn't set foot in France for a few more weeks. In fact, he was back holding court at the Dorchester that evening. But a reader could be forgiven for assuming Hemingway had played a much larger role in the action than likely was true.

He closed his account for Collier's this way:

Real war is never like paper war, nor do accounts of it read much the way it looks. But if you want to know how it was in an LCV(P) on D-Day when we took Fox Green beach and Easy Red beach on the sixth of June, 1944, then this is as near as I can come to it.