George Hicks brings the sound of D-Day to your living room

As the 77th anniversary of the Normandy landings approaches, we’re taking a look at how D-Day was covered at the time.

As the final minutes of the day the world had anticipated for years ticked away, George Hicks went topside on the USS Ancon to record a summary of what he had seen and heard on D-Day. The 38-year-old Blue Network correspondent lugged a 50-pound Recordgraph film recorder to the deck and set up near one of the Ancon's four twin 40mm antiaircraft gun mounts.

The Recordgraph was relatively new technology, providing the opportunity to record audio on-site in unstable conditions that didn't particularly suit the acetate discs that were conventionally used for recordings at the time. The U.S. Navy had purchased several to allow combat historians to record interviews in the field beginning in 1943 in the Pacific theater and had loaned a few to broadcast networks for invasion coverage. About the size of a portable typewriter, the machines (pictured in the foreground above) resembled the home movie projectors popular in the 1970s.

With the film rolling, Hicks began his description of the scene off what we now know as Omaha Beach. The Ancon -- which was not named in his broadcast -- was the headquarters ship for the Allied force off Omaha, so it stayed farther offshore than the battleships and destroyers providing cover on the landing beaches.

At the start of a recording that would eventually run about 13 1/2 minutes, Hicks discusses the lack of any German opposition by air or sea craft. Before him, the Allied armada spreads out "just like black shadows on the water," occasionally blinking messages to one another via Morse code. At that point, a plane drones overhead.

That baby was plenty low. I think I just made the statement that no German planes had been seen, and I think there was the first one we've seen so far. He came very low, just cleared our stack, and as he passed he let go a stream of tracers that did no harm.

It's evident the pass has caught everyone off-guard, as there is no reply from the Ancon's antiaircraft batteries. That would change momentarily, creating the soundtrack for an instant broadcast journalism classic that brought the sounds of battle to a public accustomed to consuming only correspondents' interpretations of the war's events.

The low-flying German plane, identified later in the broadcast by Hicks as "probably" a Ju-88 dive bomber, sets battle stations sirens wailing on the Ancon and neighboring ships. Flak begins to fill the air just as the clock strikes midnight, ushering in June 7, 1944, and Hicks switches to play-by-play mode as the action intensifies.

These planes you hear overhead now are the motors of the Nazis coming and going in the cloudy sky. ... The tracer lines keep arcing up into the darkness. Very heavy fire now off our stern. More ships in that area firing bursts, and the flak and streamers going out in a diagonal slant -- right over our head now!

The sound of antiaircraft fire drowns out Hicks' voice as gunners try to find the range, a cycle that continues for the next few minutes as the planes make passes over the ships.

At one point the raiders leave the immediate area and Hicks tells his audience, "You'll excuse me, I'll just take a deep breath for a moment and stop speaking."

He follows up by noting that the attack "seems to have died down," but 30 seconds later his voice rises to a shout ...

Here we go again, another plane's come over! The tracers are making an arc right over our bow now. ... Tracers still coming up, and now the plane has probably gone beyond.

It looks like we're going to have a night tonight. Here we go, boys! Another one coming over. The cruiser right alongside of us is pouring it up! Streams of tracer, hot fire coming out of all the small ships, and large as well. Something burning is falling down through the sky and circling down, maybe a hit plane!

Hicks lets the sound of battle take over for several seconds, with numerous guns blasting away, then the shouts and cheers of crew members join the din.

There we go -- they got one!

Hicks has an exchange with a nearby crew member, on mic though unintelligible at times, as the sky goes quiet for a few moments.

The lights of that burning Nazi plane are just twinkling now, in the sea, and going out. Then the tracer starts up again and there's warning of another plane coming in. It's now 10 past 12 and the German air attack seems to have died out.

The planes have indeed gone for good, and Hicks recaps the action, naming the men at the No. 42 gun battery who shot down the enemy plane.

It was Ensign William Shriner of Houston, Texas, who's the gunnery control officer, and Seaman Thomas Squirer of Baltimore, Maryland, handled the direction finder. It was their first kill for this gun, and the boys were all pretty excited about it.

Increasingly confident that the skirmish is over, the correspondent quickly wraps up his broadcast.

Meantime now, the French coast has quieted down. There seems to be no more shelling into it and all around it is darkness and no light or no firing. Now 10 past 12, the beginning of June 7, 1944. This is George Hicks speaking. I now return you to the United States.

Hicks retired to his cabin, wrung out from the stress of the last few days, and assessed his performance. He looked back on the moment in a January 1945 radio interview:

Personally, I thought I had muffed the recording. I couldn't remember what I had said and the firing had been so heavy that it had knocked coherency and sense out of me. I was tired -- so were the men. It occurred to me that we had been in danger -- that's why I talked about the beauty of the quiet sky after the raid had passed. I was deeply grateful that our men had made the shore -- that they were still living. I was glad June 6th was over.

As Hicks contemplated the day and what would come next, a courier left the Ancon with the recording and other dispatches. It arrived in London several hours later and was distributed among the U.S. networks -- Blue, CBS, NBC and Mutual -- under the pool agreement in place for the invasion.

All four networks ran Hicks' report at 11:15 p.m. ET on June 7, and it captivated audiences desperate for insight into the most anticipated story in years. The next few days saw it "repeated innumerable times in response to the great listener demand," Broadcasting magazine reported in its June 12, 1944 issue.

Hicks had no idea his report had been an immediate sensation. He remained based on the Ancon for several days, going ashore in France a couple of times and filing more reports via courier. He finally arrived back in Southampton on June 13, a week after D-Day and 11 days since he stepped aboard the Ancon in Portland.

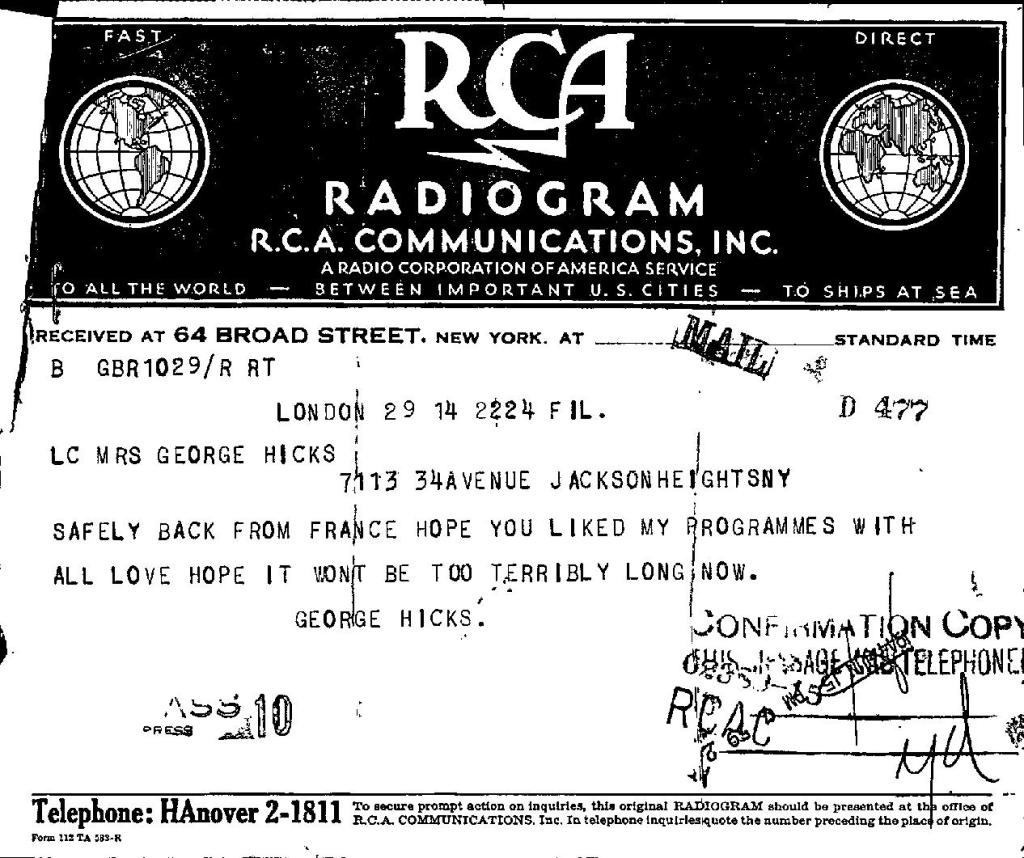

Back in London later on the 13th, he fired off a telegram to his wife, Anne, back at home in Queens.

It was about this time, as he returned to the Blue Network offices in London, that he began to get a grasp for the impact his broadcast had made. The network, a former arm of NBC that was still finding its feet as an independent entity, was ecstatic. (Blue would become the American Broadcasting Company, ABC, in June 1945). On June 30, the network sent Anne Hicks a check for $1,000 (nearly $15,000 today) as a bonus for her husband's "wonderful and loyal service."

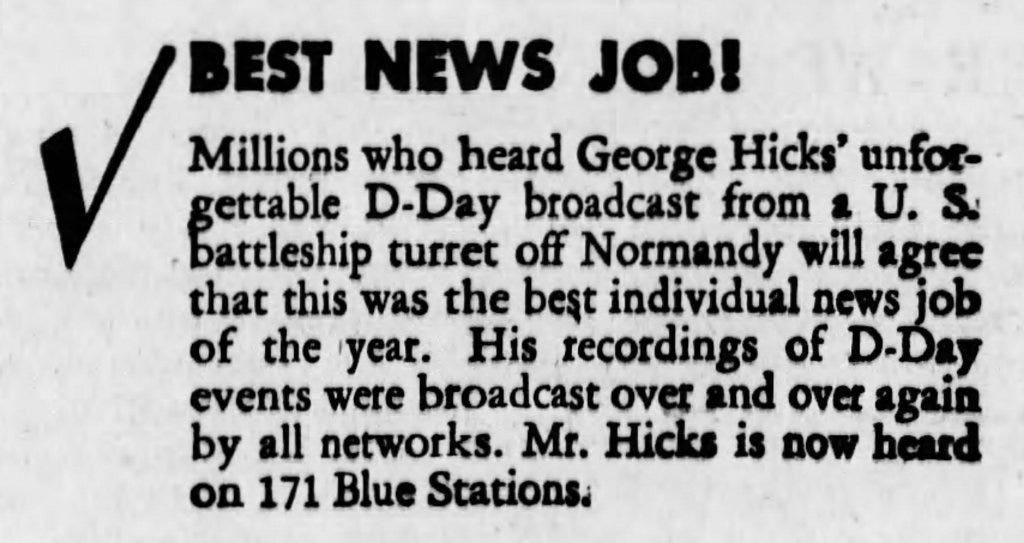

Hicks' peers took notice, too. When the trade publication Motion Picture Daily conducted its annual year-end poll of editors and writers covering the broadcast industry, Hicks' report was an easy choice for individual "Best News Job" honors (alongside CBS as the best network for news).

"The nation's radio editors and critics heaped great praise on George Hicks of the Blue Network for his handling of reports from the invasion beachhead in Normandy on D-Day, reports which were carried on all networks," Motion Picture Daily wrote in announcing the poll results in its December 8 issue. "Their vote is that his was the best individual news job performed in radio in 1944."

The New York Herald Tribune concurred, pronouncing Hicks' "now-classic description" the "Best News Broadcast" in its 1944 radio awards: "Mr. Hicks described the scene quietly, concisely, almost gently at times, though death might have struck him from the skies at any moment."

That assessment goes a long way toward summing up the appeal of Hicks' broadcast. He lets the action breathe, and his personal stake in the events in evident. The end result is an unquestioned slice of realism in an era of scripted radio dramas rife with canned sound effects.

A month and a day after returning to England, Hicks departed again. He caught an LST back to France and joined Gen. Omar Bradley's press camp before hooking on with the 35th Infantry Division near St. Lo.

He remained with the Allied armies for the coming months and was eventually wounded during the Battle of the Bulge when a German bomb hit a hotel in Chaudfountaine, Belgium, on December 23. Hicks, two other correspondents, and about 20 soldiers incurred superficial wounds from flying glass in the attack, which killed United Press correspondent Jack Frankish and three Belgian soldiers.

Thankful to have escaped with his life, Hicks made for Paris and caught a plane on New Year's Eve for the long journey home. He arrived back in New York two days later. He would return to Europe to cover the conclusion of hostilities in that theater before leaving Southampton via ship on May 24, 1945, and arriving in New York on June 3, nearly a year to the day of the broadcast that made him famous.

George Hicks died of cancer in 1965 at age 59, but his work on D-Day continues to make the news decades later.

In 2012, the Library of Congress selected his broadcast as one of 25 annual additions to its National Recording Registry, which showcases "the range and diversity of American recorded sound heritage in order to increase preservation awareness."

In October 2019, a researcher named Bruce Campbell donated what is believed to be the original tape of Hicks' broadcast to the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Virginia. As aWashington Post story recounts, the film was among a cache of items left in a Long Island cabin Campbell had purchased in 1994. He kept the film in storage for years before deciding to try and find out what he had. Campbell eventually tracked down an audio expert in England who built a new version of a Recordgraph that would play the film, and was stunned by what he heard.

That Long Island cabin, it turns out, had been the vacation home of Albert Stern, the vice president of the company that made the Recordgraph.