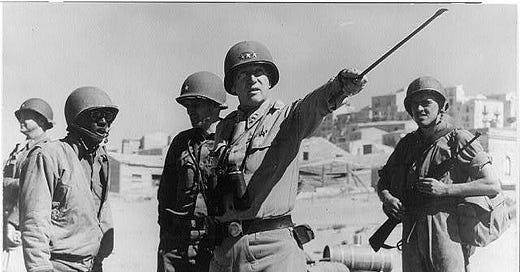

Gen. Patton and the slaps heard 'round the world

At 7 p.m. ET on Sunday, Nov. 21, 1943, Drew Pearson opened his regular 15-minute radio program on the Blue Network with a typically sensational story.

The multimedia muckraker reported the shocking news that Lt. Gen. George S. Patton had struck a soldier in a field hospital in Sicily and had been "severely reprimanded" for the act by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. Pearson added that he didn't expect Patton to be used in "important combat" again.

The Associated Press contacted the War Department for a reaction that evening and got a "no comment." The following day, Eisenhower's headquarters in Algiers released a statement saying, among other things, "General Patton has never been reprimanded at any time by General Eisenhower or by anybody else in this theater." The statement did not directly address the report of an altercation with a soldier.

But the War Department and Eisenhower were well aware of what had happened. In early August, Patton slapped not one but two soldiers in separate incidents a week apart. A week after the second encounter, Eisenhower sent Patton a strongly worded letter expressing shock at the allegations but telling him he had no plans to open a formal investigation.

The correspondents covering Seventh Army knew about all of this, too. They just didn't report it until Pearson forced their hand.

The twin incidents that nearly derailed Patton's career occurred on Aug. 3 and 10 in Sicily. In the first, Patton was visiting the 15th Evacuation Hospital near Nicosia when he encountered Pvt. Charles H. Kuhl of Mishawaka, Indiana, who did not appear to have any physical injuries.

When the general asked what was wrong with him, Kuhl acknowledged that he was "nervous" and said "I guess I can't take it." Patton immediately slapped Kuhl in the face with a pair of gloves and grabbed his collar, dragging him out of the medical tent while screaming about the private's cowardice the entire time. He punctuated the show by kicking Kuhl in the rear as they exited the tent.

Kuhl was in fact suffering from malaria and had a temperature of 102.2 degrees upon further examination. He was later sent back to North Africa for treatment.

A week later, Patton strolled into the 93rd Evacuation Hospital near Santo Stefano and once again singled out a man whose condition appeared in contrast with the obviously wounded patients around him. Pvt. Paul G. Bennett of the 17th Field Artillery Regiment had in fact been ordered back to the hospital by medics despite his pleas to remain at the front.

The North Carolina native again made the mistake of mentioning "nerves" to Patton, who shouted that the 5-foot-4 soldier "ought to be lined up against a wall and shot" then yanked his own pistol from the holster. After waving the gun in Bennett's face, Patton slapped the man with his hand, then yelled to the hospital's commanding officer, Col. Donald E. Currier, that he wanted the private removed from the hospital before turning and striking Bennett again.

It was the latter incident that eventually made its way up the chain of command. Some hospital staff members who witnessed the Bennett altercation felt the general had been out of line and II Corps surgeon Col. Richard T. Arnest wrote a report and submitted copies to his commander, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, and Brig. Gen. Frederick A. Blesse, the chief surgeon at Allied Headquarters in North Africa.

Blesse forwarded the report to Eisenhower, who ordered an investigation. On Aug. 16, Lt. Col. Perrin H. Long submitted a report summarizing both incidents after speaking to medical personnel who had witnessed Patton's actions. At the bottom, he wrote:

The following day, Eisenhower wrote a five-paragraph "personal and secret" letter to be hand-delivered to Patton by Blesse, with Long's report attached. Eisenhower bends over backward giving Patton the benefit of the doubt, acknowledging that "firm and drastic measures are at times necessary" in battle situations. "But this does not excuse brutality, abuse of the sick, nor exhibition of uncontrollable temper in front of subordinates."

He makes clear to Patton that he has no intention of conducting a formal investigation and that their correspondence will remain in his "secret files," but leaves no doubt that similar behavior will not be tolerated going forward: "You must give to this matter of personal deportment your instant and serious consideration to the end that no incident of this character can be reported to me in the future."

While Eisenhower requested a response from Patton and "strongly advised" the general to apologize to both privates "provided there is any semblance of the truth in the allegations," he seemed to hope that would be the end of it.

But too many people already knew what had happened, and they were talking about it.

With word of Patton's actions all over the GI grapevine in Sicily, correspondents covering Seventh Army got wind of what had happened almost immediately.

They wanted to ensure they had a full picture of the situation, so veteran correspondent Demaree Bess of the Saturday Evening Post took the lead in assembling a report of his own. He and Merrill "Red" Mueller of NBC interviewed doctors and patients who had witnessed the incidents and pieced together much the same picture the medical staff already had sent up the chain.

By this point, the fighting in Sicily was over. On Aug. 17, the last German and Italian troops on the island completed their evacuation across the Strait of Messina to mainland Italy to wrap up a week-long withdrawal operation.

Quentin Reynolds of Collier's arrived in Sicily around this time and quickly found there was nothing much for him to write about. So he planned to catch a ride back to Algiers with Gen. Terry Allen, who had been summoned to Eisenhower's headquarters. He described the scene in his 1963 book, By Quentin Reynolds:

Since Terry Allen had room on his plane, I suggested to Bess and Mueller that they come along to headquarters and see what Eisenhower might have to say about the situation.

In Algiers, when I telephoned (Eisenhower's aide) Harry Butcher for an appointment, he said, "I know what you're coming to see him about. The general hasn't slept for two nights, worrying about it."

Eisenhower listened most unhappily while Mueller and Bess recounted what the witnesses had told them. Then he managed a smile. "You men have got yourselves good stories," he said, "and as you know, there's no question of censorship involved."

"Quent and Mueller and I have been discussing what would happen if we report this," Bess said quietly, "and our conclusion is that we're Americans first and correspondents second. Every mother would figure her son is next."

Then Mueller said that we were not only going to kill the story but deny it if any of the other correspondents broke it.

All indications are the correspondents' reticence in publishing the story didn't stem from any particular personal deference to Patton. Though his exploits made for great copy, he was a polarizing figure among the press just as he was among most of his various constituencies. As Milton Bracker would write in The New York Times a few months later, "Many people do not like General Patton and not all respect him."

According to Butcher, Reynolds mentioned during the meeting that there were "at least 50,000 American soldiers who would shoot Patton if they had the slightest chance" -- an obvious bit of hyperbole that nonetheless made it clear the general wasn't universally beloved.

Eisenhower, meanwhile, cultivated a cordial relationship with the press and would continue to do so for the rest of the war, a key bit of political calculus that helped him exert the influence he did as Supreme Allied Commander.

In this case, his deft handling of the situation and the correspondents' knowledge of Patton's value to the Allied effort combined to do the nearly impossible. Wrote Reynolds:

There were sixty American and British correspondents in Algiers and Sicily at this time, and despite the fact that neither Eisenhower nor General (Robert) McClure, in charge of press relations, exerted even indirect pressure, no one broke the story.

Not yet, anyway.

Just over three months after that Aug. 19 meeting at the Hotel St. Georges in Algiers, Pearson broke the gentleman's agreement he had never been party to.

The syndicated columnist and broadcaster reportedly heard the news from one of his best sources, OSS official Ernest Cuneo, an attorney who had played in the NFL and spent time as a journalist before the war (and would later become a newspaper executive).

But Pearson insisted he didn't just rush the news on the air. In the days after his Nov. 21 broadcast, he told reporters he had cleared the report through the Office of Censorship (after a four-hour delay) and checked with "high War Department officials" who advised him to use his own judgment in broadcasting it.

Correspondents in the field had long since made their peace with the story and had little cause to be upset after Pearson's report, but the Army's public relations apparatus quickly became the target of their ire. In The Day of Battle, Rick Atkinson notes that the initial statement from Algiers of any reprimand -- engineered by Eisenhower's chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith -- "made matters worse by disingenuously insisting that Patton had not been reprimanded, distinguishing between an official censure and Eisenhower's personal castigation in August."

Writing in the Nov. 24 New York Times, Milton Bracker said the statement "disgusted everyone who heard it. The feeling was that the Army should either have ignored Mr. Pearson's broadcast or answered it with the whole truth."

It would be some 36 hours after Pearson initially went on the air before correspondents got the full, official version of the story at a 10:30 a.m. news conference in Algiers on Nov. 23. In addition to a tepid apology of sorts by Smith, who was not named in the stories, Merrill Mueller appeared at the podium to recap the reporters' initial findings (Bess had since returned to the United States).

Edward Kennedy's Associated Press story that hit the wire that day makes clear immediately that the Patton incident had long been known by those on the ground -- without acknowledging the self-censorship that had occurred.

It was disclosed officially Tuesday that Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., had apologized to all officers and men of the Seventh Army for striking a soldier during the Sicilian campaign.

At the same time Allied headquarters said that correspondents might reveal all of the facts they knew of the incident which since last August has been one of the main subjects of discussion among soldiers in this theater.

Note the singular"soldier" in Kennedy's lead. The details that emerged at this point concerned only the Bennett incident, though the private went unnamed. Kennedy wrote:

The facts concerning the soldier were later ascertained: He was a regular army man who had enlisted before the war from his hometown in the South. He had fought throughout the Tunisian and Sicilian campaigns and his record was excellent. He had been diagnosed as a medical case the week previously, but had refused to leave the front and continued on through the strain of battle. He finally was ordered to the hospital by his unit doctor.

After Patton left, the soldier demanded to return to the front. This request was refused at the time but after a week of rest, he was in good shape and returned to his unit at the front. Immediately after the incident the soldier was reported in a miserable state. As a regular army man with pride in his record, he felt his whole world dashed to pieces.

"Don't tell my wife! Don't tell my wife!" he was quoted as saying by persons who talked to him later.

So, what of Kuhl's story, the first of Patton's outbursts? Here, things initially got a bit muddled.

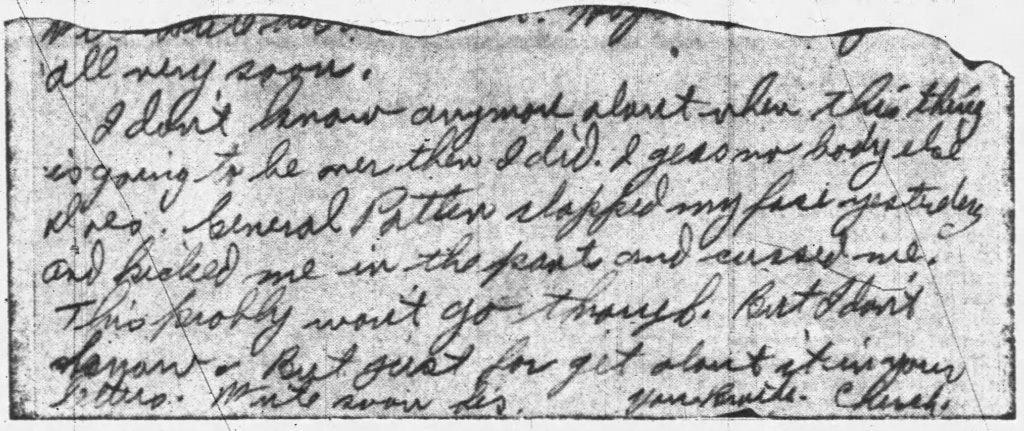

After hearing the initial report about the general striking a soldier, Herman F. Kuhl of Mishawaka, Indiana, immediately remembered a letter his son, Charles, had written to his wife Luretta. It was dated Aug. 4.

"General Patton slapped my face yesterday and kicked me in the pants and cussed me," Charles wrote his wife. "This probably won't go through [censorship]. But I don't know. But just forget about it in your letters."

In another letter, Kuhl told his family he had been flown to North Africa to appear at a hearing, and that Patton had apologized to him in person. The Kuhls had kept the news to themselves out of deference to their son's wishes, but once the news broke, Herman Kuhl brought his son's original letters to the South Bend Tribune and shared the story.

The tale dominated the Tribune's front page on the evening of Nov. 23, but reporters John F. Carroll and W.R. Walton could tell something didn't quite add up.

"Details of the Kuhl incident with Gen. Patton do not coincide in some respects with the versions reported in an Associated Press account from allied headquarters, Algiers," they wrote. Later in the story, they note that Kuhl had trained at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, after entering the service, which "might explain why the Associated Press dispatch referred to the soldier as being from the south."

On Nov. 25 -- Thanksgiving Day -- Secretary of War Henry Stimson told reporters in Washington he was aware of only one slapping incident and didn't know the name of the soldier involved, adding that he was awaiting a full report from Eisenhower. He got it the following day and read it to the Senate Military Affairs Committee, revealing for the first time that there had in fact been two separate incidents of Patton striking soldiers.

The additional revelation didn't appear to make many waves in terms of the way Patton's behavior was discussed in the media. The initial reports already had spurred calls for an investigation by members of Congress and spawned damning editorials in some newspapers (though hardly all).

Horse-race reporting of the type generally seen around political campaigns kicked in immediately, typified by numerous stories in the coming days claiming that the majority of the troops still supported Patton and public opinion polls also were trending firmly in his favor even as sabers rattled on Capitol Hill.

There also was no shortage of inward-looking pieces in the press about the correspondents' role in the cover-up. Milton Bracker weighed in on the topic for the New York Times on the day of the first official announcement:

The Patton story was known in substance to virtually every soldier in this theatre and certainly to every war correspondent since shortly after the incident happened. Yet no one tried to write it. That might have been an error in judgment on the part of all concerned. Unquestionably it was believed that the story would be completely censored.

But, in fairness to the censorship, which has tended to become increasingly liberal here, it may be said that as many and probably more men did not attempt the story because of their general feeling that it would hurt the war effort in this theatre rather than because of fear that censorship would nullify the effort.

Eisenhower acknowledged his gratitude when the heat was on, including a hat tip to the correspondents in his Nov. 26 statement to Stimson:

I commend the great body of American newspapermen in this theater because all of them knew something of the facts involved and some of them knew all, including the corrective action taken and the circumstances that tended to ameliorate the obvious injustice of Patton's acts.

These men chose to regard the matter as one in which the high command acted for the best interests of the war effort and let the matter rest there. To them I am grateful.

After the initial firestorm died down, the principals went about their business for the rest of the war.

Patton would be sidelined from the heat of the action temporarily, remaining in Sicily as Gen. Mark Clark led American forces into mainland Italy. Patton would also miss out on command of ground forces in Operation Overlord the following year, with Omar Bradley earning that duty.

Even as Patton idled, the Allies put him to good use, capitalizing on the Germans' obsession with the flashy general by making him a centerpiece of their pre-Overlord deception campaign, Operation Fortitude. An elaborate intelligence operation leaked to the Germans that Patton had been put in command of the fictional First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) in England, and even after the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, many in the German command believed those assaults were simply a diversion to distract their attention from the real invasion that must be still to come from Patton's forces.

Patton would of course go on to bolster his reputation while leading Third Army across Europe after a foothold had been established. After Germany's surrender, Patton served as military governor of Bavaria for a time before retiring to more conventional occupation duty in the fall of 1945.

A car accident in Germany on Dec. 8 of that year left him paralyzed from the neck down, and he died 13 days later at age 60.

The man whose unsolicited encounter with Patton set the entire public relations fiasco in motion, Paul G. Bennett, was never named in contemporary news reports. The first apparent identification of him as the other slapping victim came in February 1947, when his mother-in-law was quoted in an Associated Press story written out of Greensboro, North Carolina. She noted that Bennett had reenlisted in the Army and was at that time stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

Bennett's initial honorable discharge papers are available online, and they show he served from his Sept. 28, 1939 enlistment at Fort Bragg through his Aug. 9, 1945 separation. During that time, he spent nearly two years overseas, returning to the U.S. in July 1944.

Bennett would go on to serve in Korea as well and would eventually move to Columbia County, Georgia, near Augusta, where he died on Christmas Day 1973 at age 51.

While Bennett kept a low profile, Kuhl's unwitting tie with Patton surfaced periodically for the rest of his life. A carpet layer before the war, he returned to that work after hostilities concluded, and later moved on to factory work for the Bendix Corporation in South Bend.

In a 1953 interview with the South Bend Tribune, he acknowledged he "never did like the war or being overseas, and I never could get used to it. But the general just didn't believe it made me sick." While Kuhl did rejoin the 26th Infantry Regiment for the Normandy invasion, he never really got past what was then called "battle fatigue" during the war -- or in the years that followed. He had a heart attack in his late 40s and said the war could well have been to blame.

Shortly after the movie "Patton" was released in February 1970, Kuhl was once again on the Tribune front page recounting his part in history, though he wasn't particularly enthusiastic about it.

"I think it should be forgotten and dead," he told the newspaper. "I've been trying to keep it quiet and I wish sometimes that everyone in the world would too. The whole experience is still nerve-wracking."

Less than a year later, Kuhl was dead at age 55, the victim of an apparent heart attack at his home in South Bend. The story in the Feb. 2, 1971 Tribune was headlined: "Services set for Patton GI."