Hanson W. Baldwin spent four months in 1937 touring the great capitals of Europe, traveling to London, Paris, Vienna, Prague, Warsaw.

The New York Times correspondent wasn’t writing slice-of-life pieces or travel columns. The series of stories he wrote throughout his trip centered on one topic: preparations for a war he deemed inevitable.

In a Times Sunday magazine piece printed that September, Baldwin laid out the situation this way:

Uncertainly clouds the skies of Europe. This is a continent in suspense — living in the present, fearful of the future. The threatening catastrophe of the next war — which many fear will be the Armageddon of Old World civilization — casts its shadow across the lives of millions. …

In some manner the threat of war and the preparations for war affect the lives of most of the Old World’s people. The political maneuverings, the strengthening of armaments, the persistent propaganda and the organization of the civilian populations for passive defense carry implications that are inescapable. Preparations for the holocaust have insidiously intruded into the normal scene until the public has become accustomed — hardened — to the idea of war.

As the Times’ newly minted military analyst, it’s no surprise Baldwin came to conclusions like this after assessing everything he saw and heard on his tour, but he was hardly an alarmist.

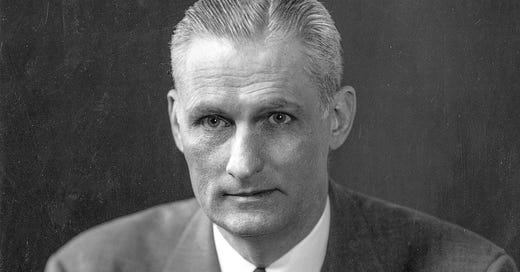

Born March 22, 1903 in Baltimore, Hanson Weightman Baldwin was a 1924 graduate of the United States Naval Academy and spent three years in the service before beginning a journalism career at his hometown Sun with a magazine piece printed in May 1928. He was first published in the Times in July 1930 and joined the staff full-time the following February, beginning an association with the paper that would last into the 1970s and include trips to the front in Korea and Vietnam.

In between, he wrote about the conflict he had foreseen during his European tour. Writing in the Times’ Sept. 3, 1939 editions after two days of fighting in Poland, he began: “German guns along the Vistula signaled last week the start of what may turn out to be another World War.”

As the importance of his beat suddenly skyrocketed, he made sure to take a wide view of the conflict. On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, the Times printed his analysis of the situation in the Pacific, which surveyed the fighting strength of the various powers at play. The piece concluded:

At this juncture Japan cannot count on much help — directly or indirectly — from Germany. She would fight for life — and unless Germany won, Japan would almost certainly lose, though not quickly.

Hours after that piece was printed, the U.S. joined a war that Baldwin would appraise from start to finish. Though he spent most of the conflict assessing events from home, he did make multiple trips to various fronts once American troops entered the arena.

Ten months after the Pearl Harbor attack, Baldwin was in Honolulu on his way to cover the Marines in the Solomon Islands. Interspersed with those stories were regular analyses of the fighting between Russia and Germany, filed from the middle of the Pacific. The collection of stories from his Southwest Pacific tour would earn Baldwin the Pulitzer Prize in Correspondence in 1943, preceding wins by Ernie Pyle and Hal Boyle in the category the next two years.

With action occurring somewhere in the world every day, it was no wonder Baldwin racked up hundreds of bylines each year during the war.

His first contribution of 1944 was a Jan. 16 story headlined “Germans are preparing for ‘D-Day in the West,” and he would spend the ensuing months anticipating the inevitable strike into Northwest Europe.

“The whole Allied strategic structure of the war will stand or fall on these great battles,” he wrote in a Feb. 29 piece. “There, on the beaches of the Continent, the strengths of the Allied armies will be illuminated, their weaknesses exposed.”

Beginning May 1, Baldwin would write almost exclusively about the coming invasion, examining every possible angle: where it would come, the equipment that would be needed, the strength of the German defenses at various points. He arrived in London in mid-May and would soon describe the atmosphere in the English countryside as “the calm before the storm.”

“Everything that can be foreseen probably has been, and the precise minuteness of the plans leaves as little as possible to chance,” he wrote May 24. “Yet the decisive factor will be the courage of the men.”

When D-Day finally came, Baldwin was aboard Adm. Alan G. Kirk’s flagship, the USS Augusta, where he remained for several days. After about a month back in London, he crossed over to Normandy in mid-July for a brief reporting stint.

That would mark his final appearance at any front during this war, but he continued to crank out reporting and analysis for the duration. On V-E Day, he looked back on the rise and fall of the fascist states that had wrought so much destruction over the previous decade.

They wanted war — the paths of glory always lead to fields of battle. They wanted war — but not the war they got. …

But now at last the paths of glory end. The death march sounds in unmuffled thunder for the men who march beneath the standards of Fascism; the riddled ranks are faint shadows of once great armies; straggling remnants, gaunt and beaten, throng to surrender.

Three months later, he immediately recognized the significance of the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima and waded into what would become his primary topic for the rest of 1945 and years to come:

Yesterday man unleashed the atom to destroy man, and another chapter in human history opened, a chapter in which the weird, the strange, the horrible becomes the trite and the obvious. Yesterday we clinched victory in the Pacific, but we sowed the whirlwind.

He continued his thoughts on the future of warfare the following day with prescient musings over the decades that would come to be known as the Cold War:

Will the atomic bomb reduce the frequency of wars; or will be merely substitute push buttons for cannons? Will man disperse and go, mole-like, underground; will he seek out new methods of defense, new weapons of offense; will wars still end in the age-old way with men on foot facing men on foot?

Will armies and navies in the old sense be forever obsolete? Will wars be essentially struggles between the mass wills of civilian populations? Or will the armed forces of the ground, of the sea and of the air, armed with new weapons, employing new techniques, still bear the bloody brunt of battle?

These are questions that no man today can answer; and it is idle and harmful speculation to attempt definitive answers to them now, before the dust has even settled over Hiroshima.

Baldwin would grapple with those issues through his retirement from full-time work in 1968, and he continued to contribute occasionally to the Times’ news and editorial pages for a few years after that.

Baldwin would live to see the end of the Cold War, but not its aftermath. He died in November 1991 at age 88.

I love this article. I wish he were still here to guide us.