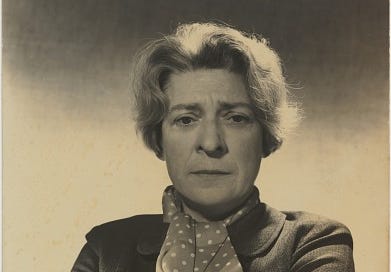

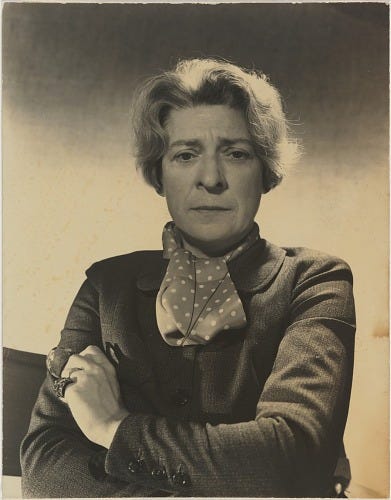

Janet Flanner's letters from Paris, and beyond

By the time the Germans marched into Paris in 1940, Janet Flanner had called the city home for 15 years while telling its stories via The New Yorker’s “Letter from Paris” department.

Like other longtime and lifelong residents, she was appalled and occasionally baffled by what she saw in the weeks and months to come as the unwelcome occupiers settled in. A full-length piece entitled “Paris, Germany” in the Dec. 7, 1940 issue catalogued the invaders curious habits and difficulties in adjusting to the norms of the land and the people they now ruled.

The acrobatics of the German salutes, the presenting-of-arms outside the officers’ hotels (with little French boys capering in imitation), the integral, muscular, Teutonic solemnity that meant so much morally to the Nazis at home have been found to mean nothing, beyond the snicker they arouse, to the French. This baffles the Germans.

Born in Indianapolis on March 13, 1892, Flanner’s byline first appeared in her hometown Star in November 1917. A decade later, writing under the pen name Genêt, she was firmly established on the Paris expat scene of the Roaring ‘20s, and would remain a fixture there for most of the rest of her life.

Flanner spent most of the occupation years back in New York, but returned to Paris as an accredited war correspondent after the liberation, setting up shop at the Hotel Scribe. There, she held court among the dozens of other writers who had made the hotel their European base, as described in Ronald Weber’s book Dateline—Liberated Paris:

In letters to friends she complained of sitting alone in her room, but among the hotel’s press, Genêt … was nearly as famous a writer as Hemingway and equally a center of attention. …

Visitors flowed in and out of her hotel room, which at time presented a problem. She enjoyed breakfasts and gossip in the hotel’s mess while also wanting to be back in her room in time for warm morning baths. One morning she found Hemingway soaking in her tub, an interlude she later related with amusement.

Though Flanner always returned to Paris, she eventually followed the Allied armies across Europe as they took the fight to the German homeland.

Her “Letter from Cologne” published in the March 31, 1945 issue examined the demolished city and its remaining residents, who sought to minimize the role they might have played in the Nazi regime. She described the newly liberated prisoners who had been housed in a Gestapo prison, lingering on a young Belgian resistance fighter whose father had been buried in the prison courtyard the night before American troops arrived.

“The son had made a cross by binding two bits of wood together with a frayed strap he had been using as a belt for his trousers,” she wrote. “Then he had prayed. He apologized to me in English for not being shaved.”

She concluded the piece with a rumination on the ancient city’s bombed-out landscape:

It is reasonable to think that Cologne’s panorama of ruin will be typical of what our rapidly advancing Army will see in city after city. Because Germany is populous, more cities have been destroyed there than in any other country in Europe. Defeat in the last war did not cost Germany a stone. This time the destroyer of others is herself destroyed.

This physical destruction of Germany is the one positive reason for thinking that this time the Allies may win the peace. However they decide to divide Germany, her cities, if they are like Cologne, are already divided into morsels of stone no bigger than your hand.

Flanner continued writing from Paris for 30 years after the war, moving back to New York in 1975 when her health began to fade. She died three years later at age 86.