'Today the guns are silent': Japan surrenders

World War II is about to come to its official closing. We are on the Pacific fleet's flagship, USS Missouri, in Tokyo Bay for the signing of the surrender of Japan, three years, eight months and 25 days since the attack on Pearl Harbor. We are 3,700 miles from there, but we have come much further than that, by way of the Central Pacific, New Guinea, the Marianas and the Philippines.

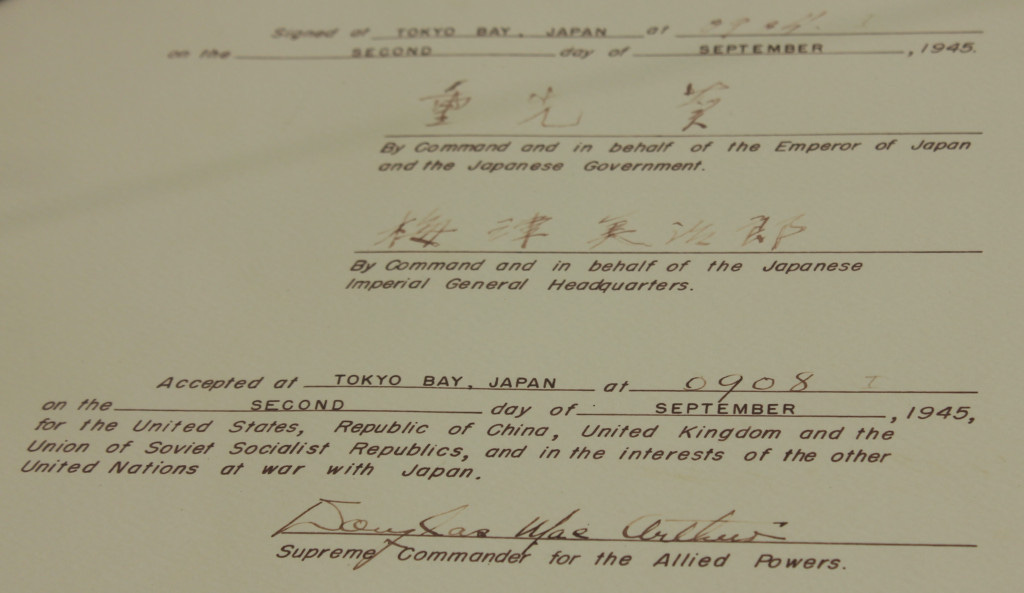

Those words from Webley Edwards of CBS greeted listeners tuning in across America to hear the news they'd awaited for so long. Japan's surrender on September 2, 1945 was a more formal ceremony than the meeting in Reims nearly four months earlier that had ended the European war, with more than two weeks of lead time after Emperor Hirohito's public capitulation on August 15 to arrange the proceedings.

Also unlike Germany's surrender, which controversially was limited to a relative handful of correspondents on-scene, reporters and photographers from around the world were invited aboard to witness the end of the war. An Associated Press story described the day as "undoubtedly the most thoroughly covered of the war in all theaters," with approximately 315 correspondents from more than a dozen countries (including Japan) aboard the Missouri for the signing.

Edwards and Merrill "Red" Mueller of NBC handled radio duties for all American broadcast outlets, with Edwards taking the lead announcer's role and Mueller serving as a kind of play-by-play man for the 20-minute ceremony, describing in quieter tones the actions, appearance and body language of the men on the Missouri's veranda deck as they worked through the machinations of surrender.

You can listen to their report from the ceremony below, along with the start of President Harry Truman's subsequent statement from the White House, which is cut off at the end of this National Archives recording.

Following the broadcast of Truman's speech, U.S. networks aired MacArthur's prepared remarks. They began:

My fellow countrymen, today the guns are silent. A great tragedy has ended. A great victory has been won. The skies no longer rain death, the seas bear only commerce -- men everywhere walk upright in the sunlight. The entire world lies quietly at peace. The holy mission has been completed.

And in reporting this to you, the people, I speak for the thousands of silent lips, forever stilled among the jungles and the beaches and in the deep waters of the Pacific which marked the way. I speak for the unnamed brave millions homeward bound to take up the challenge of that future which they did so much to salvage from the brink of disaster.

The open-door policy for accredited correspondents led to numerous metropolitan newspapers having one of their own on the scene and not having to rely solely upon wire-service reports.

John S. Knight, the 50-year-old president and editor of the Akron Beacon Journal, was among those aboard that day. His story, which was printed in multiple newspapers owned by his family, began:

ABOARD THE USS MISSOURI IN TOKYO BAY -- One of the most impressive pageants in world history was enacted on the deck of the great battleship Missouri this Sunday morning when 11 blank-faced Japanese formally surrendered their nation to Gen. Douglas MacArthur and a mighty array of United Nations commanders.

We watched the proceedings from a box seat atop a sixteen-inch gun turret. It commanded a sweeping view of the whole panorama on the captain's promenade deck just below us.

There was a hometown reunion atmosphere among the generals and admirals who started arriving shortly after the white-clad Missouri band played "The Star Spangled Banner" and "God Save the King." There were exclamations of "Hello, Jock, haven't seen you for ages," and so forth.

Witnessing the moment must have been particularly bittersweet for Knight, whose son John Jr. had been killed in action in Germany five months earlier.

While many correspondents took the same approach as Knight, describing the highlights of the ceremony as a whole, some stuck with the mission they had fulfilled since arriving in theater to cover the war: finding a local angle.

John E. Jones' account in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette got the names and home addresses of area sailors on the front page while weaving in details of the ceremony:

Stationed in the forecastle, Seaman Nathan Luterman, 332 Burrows street, Terrace Village, could see the Japanese foreign minister (Mamoru Shigemitsu) hobble on an artificial leg up to the green-draped surrender table and affix the signature that spelled Japan's doom as a military power.

And to Seaman First Class Andrew Conrad, 4089 Cabinet street, Pittsburgh, the whole proceeding seemed "like a dream -- a good dream -- come true."

"I saw everything," he said. "I saw Admiral Nimitz, General MacArthur, the British, French and Russians, and I saw them all sign."

The group of correspondents aboard included four representatives of the Black press, including Deton J. Brooks and Enoc P. Waters of the Chicago Defender. Brooks, who had worked as a teacher in Chicago for more than a decade before becoming a war correspondent, mused on what had brought the world to that moment.

As I sat above the surrender stage, where generals and admirals stood jammed at erect attention while brightly-uniformed delegates of many nations enacted this simple scene, my thoughts flashed back to millions of ordinary soldiers -- both black and white -- who had made this ceremony possible.

I saw clearly the picture of glistening, barebacked engineers ploughing through the steaming jungles of Burma and other Negro troops, either sweltering or drenching in equally dense jungles of Bougainville, Leyte, New Guinea and Iwo Jima -- building roads, hauling supplies, or like the 93rd Infantry Division or the 24th Infantry, fighting their way ever eastward, helping to tighten the knot making today's formalities possible.

These men were not present, the actors in today's drama were leaders of government. But it was the spirit of their deeds which caused four Negro correspondents to travel thousands of miles by sea and air to act for them by proxy, so to speak, at this final act of war which so vitally affected their lives, and to whose victory they contributed so much.

Though the vast majority of the men aboard that day were white, some 60 Black mess stewards from the Missouri observed the ceremony as well. Charles H. Loeb of the National Newspaper Publishers Association sought out some of those men to get their thoughts.

One of them, Seaman First Class Willie W. Booth Jr. of Baltimore, summed up the group's hopes of real change at home after years of turmoil overseas:

"All of us, of course, are hoping that our service to our country will be rewarded by better chances to live in our various communities as first-class citizens. We are not too interested in bonuses, special service men's concessions or in anything special.

"We only want a chance to work where we show ability for the job, to continue our education in schools of our choice, to have a vote in whatever community to which we return.

"This is what we've fought for and will continue to fight for when we go back home."