Joe James Custer at Savo Island

As the final minutes of Aug. 8, 1942 ticked away, United Press correspondent Joe James Custer retired to bed in his cabin aboard the USS Astoria. The day before, the cruiser had supported the Marines as they landed on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, and she was now patrolling between the two, east of Savo Island.

Custer didn’t get much sleep on the night that would permanently alter the course of his life.

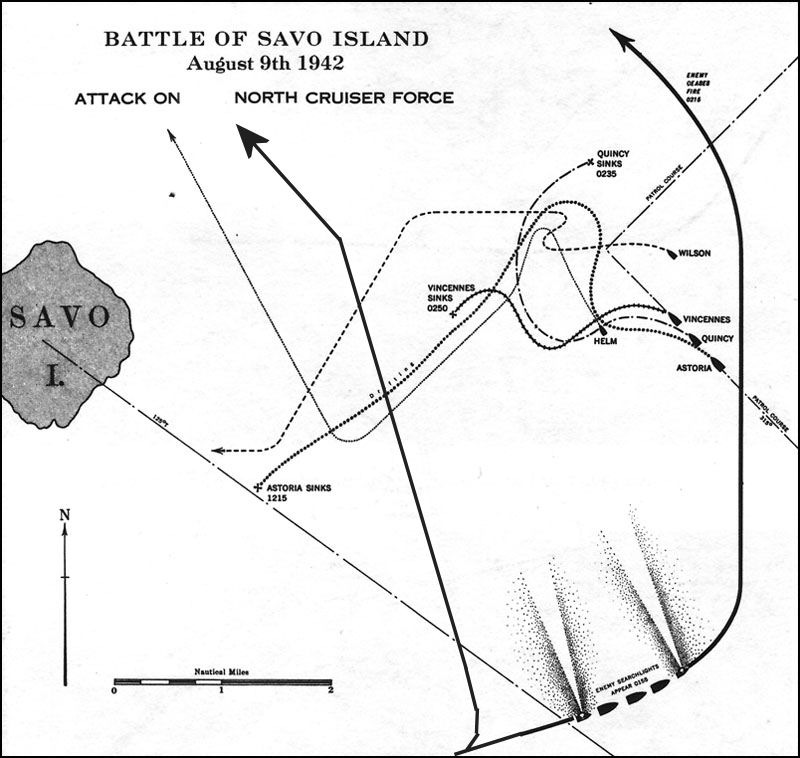

Around 1:50 a.m. on Aug. 9, general quarters sounded aboard the Astoria. The cruiser was illuminated in the darkness by searchlights beamed from Japanese ships that had stumbled upon the U.S. patrol, and they opened fire.

Shells whistled through our superstructures. Debris and shrapnel fell over the bridge where I stood. Everything seemed to be flying.

I scrambled to the side of the ship, and there I could see a fire amidships. I went back into the shack on the bridge to get a lifejacket.

I felt light, flaky debris on the back of my neck. It burned.

Four Japanese ships were raining fire on the Astoria and the nearby Vincennes and Quincy as the American crews struggled to get their bearings and respond.

It was an old-fashioned naval gun battle, one of the last of its kind as the emphasis shifted to carrier-based aircraft and submarines, and Custer couldn’t resist the spectacle before him.

We squeezed down a ladder to the deck below and we could see star shells and splashes where shells were falling short. Blue columns of water rose in huge geysers. Men were swearing but on the whole were fairly calm. I saw no panic.

A man was spraying water on the gundeck and I kept edging forward unconsciously to see what he was doing. Just then there was a helluva explosion and a fragment hit my left eye.

I spun around and felt a sharp, awful pain. Blood streamed down my face. I couldn’t see anything. One of the men said, “Lean on me.” We stood there about 10 or 15 minutes.

I felt giddy from the smoke and fumes. The captain gave orders for all wounded and disabled men to be moved to the forecastle and I started forward, still leaning on one of the men. …

Later a destroyer took the wounded off and I went with them. Then we transferred to a relief vessel where some of my shipmates were surprised to see me. They had given me up in the confusion.

The Battle of Savo Island was one of the worst defeats incurred by the U.S. Navy during World War II. Quincy and Vincennes sank within an hour of the start of the engagement, and Astoria lasted about 10 hours before she went down around midday.

Custer was off the ship by then and eventually ended up at a naval hospital, where X-rays determined that a shell fragment was embedded behind his left eye. It became infected and doctors on the scene ordered him sent back to Hawaii for further treatment. In the meantime, he dictated stories on the Guadalcanal landings and his own injury that would hit the wires weeks later after being cleared by censors.

By mid-September he was at Queen’s Hospital in Honolulu, where doctors did what they could to save his eye, including removal of a 15-millimeter piece of shrapnel Custer would show off to a prominent visitor: Adm. Chester Nimitz. The correspondent would spend four months in the hospital, enduring four operations during that span, but never regained his sight in the eye.

That was the end of the 33-year-old Custer’s career as a frontline war correspondent. Before the war, he had worked mostly as a sportswriter for a variety of newspapers, first in San Francisco and San Jose and later in Honolulu, where he joined the UP staff.

After recovering from his injury, Custer headed to New York to work on UP’s national sports desk. He wrote a book about his Astoria experience titled Through the Perilous Night, which was published in 1944, and moved back to Hawaii for good in 1948.

He would work in public relations, provide commentary for two Honolulu radio stations, and serve as executive secretary of the Pacific War Memorial Commission for seven years.

On June 20, 1965, he suffered a heart attack while playing bridge with his wife and some friends at his home. Custer was rushed by ambulance to Queen’s Hospital, where he had spent all those months recovering from his wound, but he was pronounced dead on arrival, three days before what would have been his 56th birthday.