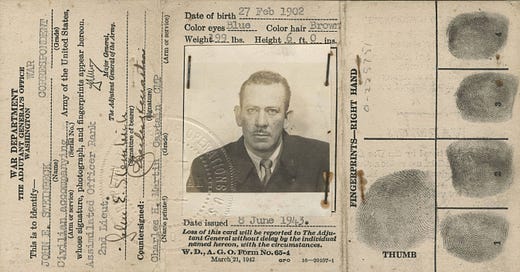

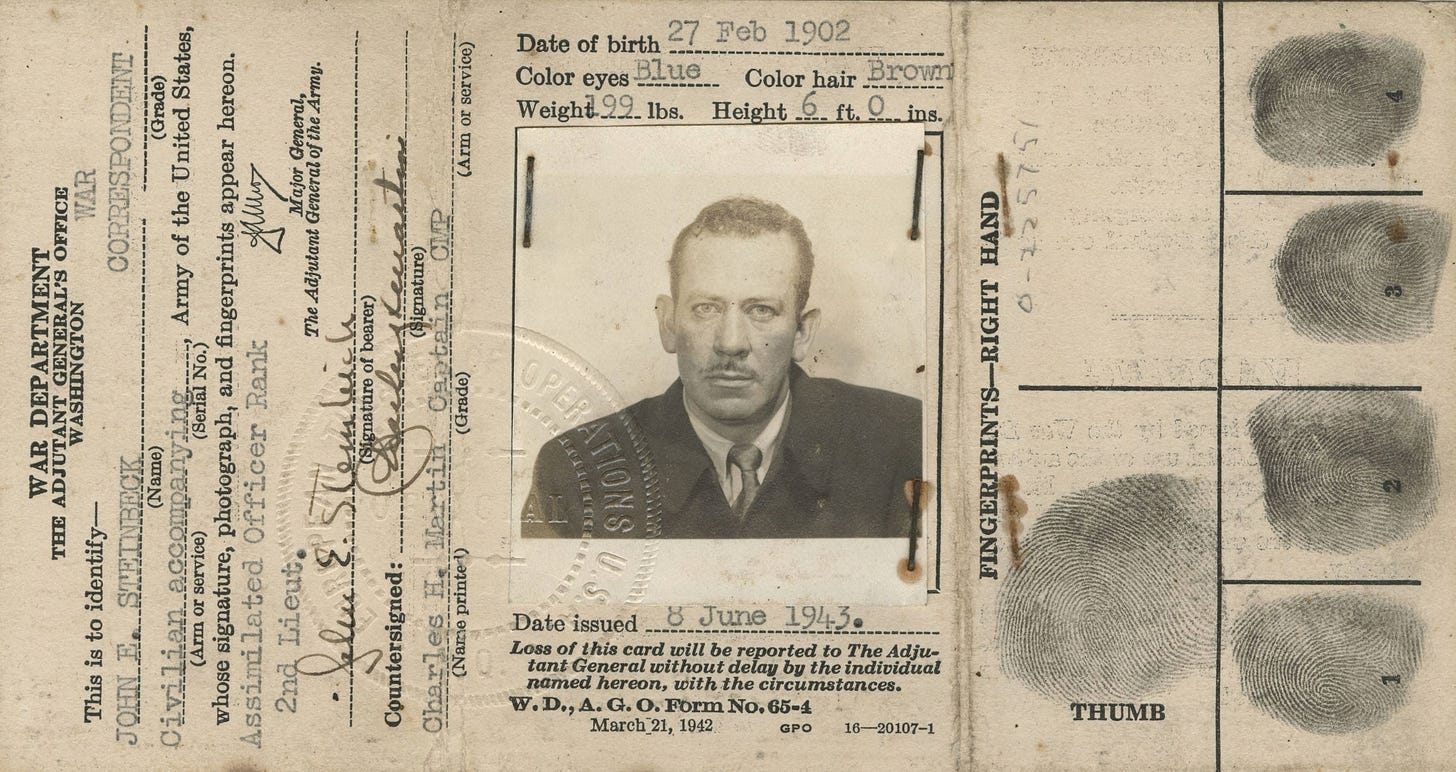

John Steinbeck goes to war

Many are familiar with Ernest Hemingway’s foray into war correspondence during World War II, but he was not the only high-profile novelist to cover the fighting for the press.

For six months in 1943, the New York Herald Tribune and a handful of other newspapers across the U.S. carried dispatches from John Steinbeck as he traveled through England, North Africa, Sicily and Italy documenting the fighting man’s life in the struggle against Nazi Germany.

The Pulitzer-winning Grapes of Wrath author was there specifically to focus on the grunt. An introductory sidebar that ran in many newspapers with the first of his stories in late June put his mission this way:

“For days he has been living with and listening to the average American soldiers. He will continue to do so at the war fronts. Things these soldiers see, hear, laugh at, will be what Steinbeck will write. Plain citizen turned plain soldier … like the kid down the block … what he is thinking, doing, and saying — that’s Steinbeck’s story!”

The 41-year-old’s first piece, datelined “Somewhere in England, June 20”, was almost entirely observational, with no quotes until the final sentence, as Steinbeck described the boarding process on the ship that would take him across the Atlantic.

A sample paragraph:

There are several ways of wearing a hat or cap. A man may express himself in the pitch or tilt of his hat, but not with a helmet. There is only one way to wear a helmet. It won’t go on any other way. It sits level on the head, low over eyes and ears, low on the back of the neck. With your helmet on you are a mushroom in a bed of mushrooms.

Once Steinbeck settled in across the pond, though, he began to intersperse interviews with those observations. One of his first stories reported in England explored the lives of gunners on U.S. Army Air Forces bombers. It concludes:

We go into a mess hall for a cup of coffee — the only good coffee obtainable in England. Sergeant Crain folds low over his aluminum mess cup which holds a full pint.

“A few days ago I killed my first man,” he says. He takes a big swallow of the scalding coffee. “I’ve been wondering about it. I’m not a killing kind of a man. I don’t get angry that way. I’ve been thinking about that man. I poured my guns into him and he died. I’ve kicked out all the things I’ve been told I ought to think about, like it’s good to kill Germans and all the other things like ‘thou shalt not kill.’ And when those things are kicked out, I find I don’t think anything about it at all. It’s just something that happened. I’m not glad or sorry. I don’t have any feeling about it at all. Isn’t that funny?”

He looks up. His eyes are the washed-blue of Texas. “Don’t you suppose I ought to have some kind of feeling about it?” he asks.

In that example, Sgt. Crain is something of an exception. Steinbeck routinely described his characters only by their rank, writing pieces as if they were scenes from his fiction. Given that style, it’s fair to presume plenty of the quotes he did use weren’t exactly verbatim, but that was hardly unusual for the era. None of the print correspondents was recording interviews on an iPhone for later word-for-word transcription.

A later dispatch, reported once again over coffee but this time in North Africa, centers on two unnamed Navy officers, a lieutenant commander and a lieutenant (j.g.), and the senior man’s elaborate metaphor for the work at hand:

“I conceive naval warfare to be much like chamber music,” he said. “Thirty-caliber machine guns, those are the violins, the fifties are the violas, six-inch guns are perfect cellos.”

He looked a little sad. “I’ve never had sixteen-inch guns to compose with. I have never had any bass.” He leaned back in his chair. “The composition — the tactics of chamber music — are much the same as a well conceived and planned naval engagement. Destroyers out, why that will be the statement of theme, the screening attack, and all preparing for the great statement of battleships.”

He leaned back farther and tipped his chair against the wall and hooked his heels over the lower rung. A lieutenant (j.g.) laughed. “He always talks like that. If he didn’t know so much about mines we would think he was crazy.”

Steinbeck returned to the U.S. that fall, but his articles continued to appear in newspapers through the end of the year. Back home, he returned to what he knew best and wrote Cannery Row, which was published at the end of 1944.