John T. Whitaker's journey from newspapers to the OSS

As the war unfolded in Europe in the spring of 1941, few American correspondents had a better grasp of the situation than John T. Whitaker. He had been reporting from the continent since 1931, first with the New York Herald Tribune and later for the Chicago Daily News syndicate, and his connections led to some of the best reported analyses of World War II.

Much of Whitaker's reporting from the late 1930s into the '40s had focused on Italy and Spain, and he made Rome his base as the war got underway. But he became increasingly critical of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler in his dispatches, prompting Mussolini's government to "ask" him to leave the country in February 1941.

Free of Italian censorship, Whitaker promptly wrote a multi-part series on what was really happening in the country. The stories received wide play in U.S. newspapers as he set up camp in Lisbon to continue his reporting. There he drew on his contacts from years in the field, with the added advantage of operators from all sides passing through neutral Portugal providing abundant sources.

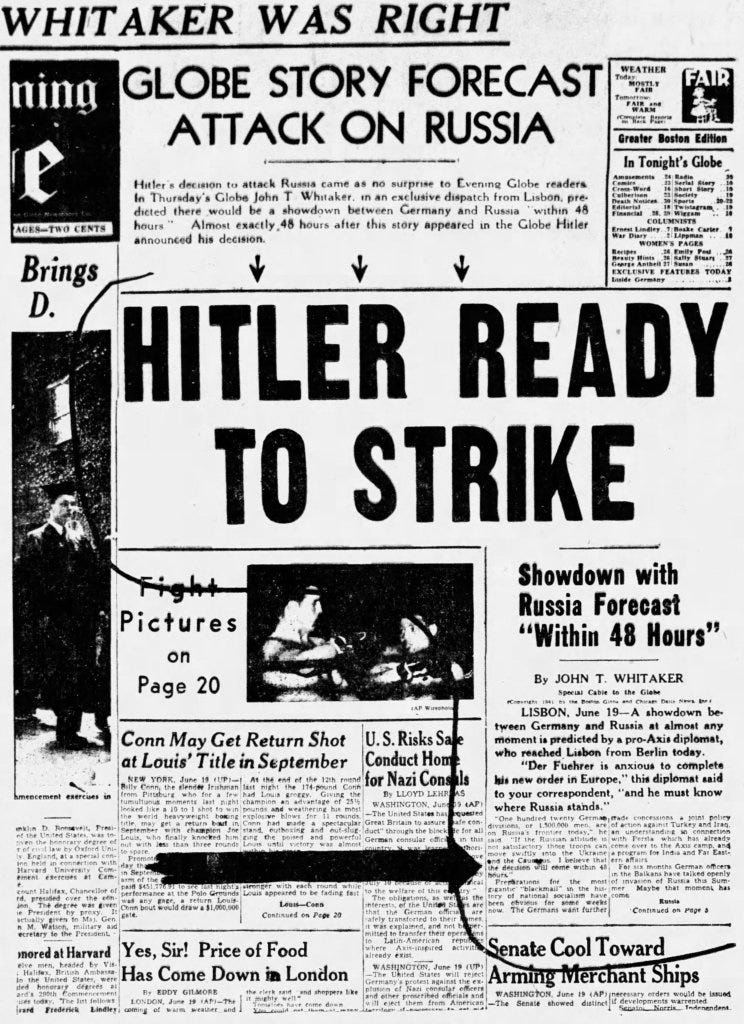

Throughout June of 1941, buzz had grown that Hitler might make a move on Russia, defying the non-aggression pact he and Stalin had agreed to nearly two years earlier. But it was Whitaker who nailed it down.

In a June 19 piece from Lisbon, Whitaker quoted an unnamed "pro-Axis diplomat" who predicted war between the countries could come at any moment.

"Der Fuehrer is anxious to complete his new order in Europe," this diplomat said to your correspondent, "and he must know where Russia stands.

"One hundred twenty German divisions, or a million and a half men, are on Russia's frontiers today. If the Russian attitude is not satisfactory, those troops can move swiftly into the Ukraine and the Caucasus. I believe that the decision will come within 48 hours."

Whitaker noted that German officers in the Balkans had "talked openly of invasion of Russia" for six months. "Maybe that moment has come," he wrote.

The next day, June 20, Whitaker filed a story reporting a rift among Hitler's advisers on whether to launch an attack. Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop led the faction opposing an invasion, Whitaker reported, while the military supported such an incursion. The reasons he laid out align well with the generally accepted thinking of German high command:

They too look at Russia as a vast reservoir of raw materials vitally necessary now that the Lend-Lease bill and the virtual impossibility of successful invasion of Great Britain makes the war inevitably a long one. But more important to them is the necessity in this immediate phase of the war of destroying the Russian military machine which, if the least efficient, is still the biggest in the world.

As the generals contemplate a long war in which America participates they want to remove from their flank this potential threat. They have carefully disarmed the conquered countries, which means virtually all of Europe, and they feel that Russia too must be beaten and disarmed.

As it turned out, Whitaker's original source was only off by a day. Early on the morning of June 22, German forces began attacking Russian positions in multiple locations, and by midday Soviet foreign minister Molotov had announced publicly that the country was under attack.

In a competitive media environment, Whitaker's reporting from a faraway land becoming reality within a span of days was news worth trumpeting in its own right. The Boston Globe was among the newspapers that ran Whitaker's pieces regularly, and it devoted quite a few column inches on Page 2 of its June 23 edition to congratulatory self-promotion:

While his clients were patting themselves on the back, Whitaker continued to do what he did best. Impressive as his pre-invasion reporting was at the time, a column filed June 23 stands up as among his most prescient efforts. It begins:

The invasion of Russia may prove to be Germany's decisive blunder leading on to as bleak a chapter for Hitler as Napoleon's retreat from Moscow. But this will be true, in the opinion of military experts, only if Hitler's enemies make it so -- or, to be more precise, if the Americans choose this moment to strike.

The first sentence of Whitaker's lead certainly held up over time. The invasion stands as the key strategic misstep for Germany in the entire war. The second sentence doesn't give the Russians enough credit for what they would be able to withstand, as they ultimately sacrificed tens of millions of their own to repel, then drive back the German invaders. But it does tee up the rest of Whitaker's piece, which urges the U.S. to enter the war immediately.

The moment has come for America to throw its destroyers into the battle of the Atlantic, ferreting out submarines and releasing British warships for service in the Mediterranean where Prime Minister Winston Churchill has little of his fleet left. The moment has come for America to throw in the vanguard of its air force to provide that preponderance of bomber strength which will give Britain mastery of the German skies while Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering's Luftwaffe is occupied with Russia's inferior but enormous air force.

This is not a Nazi war against Communism. There is no essential difference between Nazism and Communism. This is a war of the German military to gain raw materials needed for the conquest of America and to destroy the Russian war machine on Germany's flank, as this correspondent revealed last week.

Whitaker goes on to assert, correctly by all historic accounts, that "America's Army is not prepared" for war, though its Navy and Air Corps are. He believes those services can offer just enough support alongside Britain's efforts to keep the Germans from focusing their full efforts on Russia. And though he doesn't believe Stalin's forces are particularly imposing on the attack, he recognizes one key difference in this situation that would once again prove rather prescient:

On the defensive the Russians will have many advantages unless they are immediately knocked out by blitz methods If the success of the mechanized invading forces is slowed up by effective bombings of Germany proper and German communications anything can happen. War is still, of all human enterprises, the one where luck remains the greatest single factor.

Whitaker would equivocate a bit over the next few days, respectful as was the entire world at the time of the German army's capabilities after its sweep through the Low Countries and France a year earlier. But his initial feel for how the Russian campaign might play out holds up well as that elusive first rough draft of history.

That isn't just an assessment from decades later, either. Whitaker's prowess for interpreting events was recognized in the moment. Back in the United States the following winter, the correspondent spoke at Emory University in Atlanta on January 8, 1942 -- a month after his hopes that the U.S. would enter the war finally were realized.

The lead of the Atlanta Constitution story the following day asserts that his "record for accurate prognostications in world affairs is perhaps better than any other foreign correspondent" before reporting Whitaker's statement that he believes the Allies have a 60-40 chance to win the war. The two main reasons behind that prediction: Lend-Lease and "the great resistance by the Russians."

Whitaker said he did not expect an imminent British invasion of Italy, which had been rumored at the time, but "does not think the Italian people would oppose a British invasion if they were confident of an Allied victory. He said the Italians hate the Germans but at the same time fear them, and the fear is greater than the hatred."

He also noted, according to the writer covering the event, Tom McRae: "An Allied invasion of the continent will be necessary to win the war, Whitaker believes, but he cannot see an attempt taking place soon. It may be as long as five years before we are ready, he said."

That prediction would again prove half-right. Surely Whitaker would have advanced his timetable if he had been able to comprehend in advance the massive industrial mobilization soon to come to America's factories.

Either way, Whitaker's days of analyzing war developments had just about come to an end. With the U.S. now in the war, the 35-year-old was not content to continue reporting on the unfolding crisis. He resolved to get involved firsthand, at significant personal cost.

The headlines practically wrote themselves, splashed across newspapers nationwide on February 3, 1942. Many of them, particularly in Whitaker's native Tennessee and at papers that had carried his dispatches, ran on Page 1.

Whitaker had injured a vertebra while boxing during his college days at the University of the South. It hadn't bothered him until about 1940 when, according to an interview his father gave to the Associated Press, he "stepped off a street curb and chanced to sneeze at the same time. This completed the fracture and he'd been having trouble with it since."

The problem how was, Whitaker had resolved to join up, and he couldn't do it in his existing condition. So he went to the Polyclinic Hospital in Manhattan in mid-January and had a surgeon re-break his back. After five months in a cast, the thinking went, it should heal properly and allow him to serve his country.

Whitaker told the AP in a story datelined February 2: "After watching them (the Germans) bully and beat a lot of poorly equipped Europeans, I'd like to participate with American troops when they make them whimper."

It was a sensational story, one media outlets were happy to tell. The Nashville Banner even editorialized about Whitaker in its February 3 editions:

He has literally had his back broken for his country, a delicate operation to correct an old injury and fit himself for service in America's armed forces. A native of the Volunteer State would hardly be expected to do less. It is the same thing -- though carried to a new extreme -- that every American young man is doing who is remedying physical defects to enable himself to serve Uncle Sam. But it was an ordeal, voluntarily undergone, that bespeaks patriotism and courage.

By 1943, Whitaker had healed from the initial surgery and a follow-up procedure and been commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Army. Soon, he was back on his old stomping grounds, serving in the psychological warfare branch in Italy. He would be awarded the Legion of Merit for his work there from September 5 through December 5, 1943. The citation praises his work in handling local media outlets to make them "useful to the Allied cause" and working with forward units to direct distribution of leaflets dropped to both German troops and Italian civilians.

"His driving energy, innate ability and constant faith in the effectiveness of a sound psychological warfare program was confirmed by his many direct aids in support of combat operations," the citation concluded.

That report came from his hometown newspaper (and former employer), the Chattanooga Daily Times, which never failed to tout Whitaker's exploits. Reports of his war work surfaced less often from late 1944 into 1945, however, thanks to a new assignment with the Office of Strategic Services.

Whitaker headed to China in March 1945 to serve as Col. Richard Heppner's deputy. For five months, he helped direct OSS efforts against the Japanese in the theater, collecting intelligence and planning sabotage raids.

Back home on leave after V-J Day, in October 1945, he regaled his former colleagues at the Daily Times with stories, many of which "cannot be put into print." With the war won, he told the newspaper he planned to return to newspaper work once discharged from military service. But no more foreign correspondent posts, please.

"I have lived abroad so much that I would like to see what the United States is like," Whitaker said.

He did eventually settle down, moving into the next phase of his life after being mustered out early the following year. On April 27, 1946, Whitaker married Elizabeth Jones McCulloch at former Interior Secretary Harold Ickes' farm in Maryland. It was the second marriage for both, and they made their home in Florida, with a summer residence in Martha's Vineyard.

It was there in early September that Whitaker began experiencing abdominal pain. He was diagnosed with peritonitis and flown to Washington for treatment at Walter Reed Hospital, but he died September 11, 1946, with his mother, brother and wife by his side. He was 40 years old.