Around 11:30 a.m. on June 6, 1994, John Wilhelm was scheduled to do an interview with CBS radio about his experiences as a war correspondent covering the D-Day landings in Normandy a half century earlier.

Wilhelm, 78, hadn’t been feeling well in recent weeks but was looking forward to the 50th anniversary of one of the defining moments in his life. Unfortunately, he didn’t get to share his story with an audience one last time, dying around 6:45 a.m. that day at his home in Maryland.

Wilhelm was born March 5, 1916, in Billings, Montana. He attended the University of Minnesota and began his journalism career at Chicago’s famed City News Bureau. He eventually hooked on with Reuters and covered the months-long fight to liberate Europe for the London-based news agency.

He was assigned to Omaha Beach on D-Day but his work never made it into print. Wilhelm lost his portable typewriter in the surf and eventually wrote out a dispatch by hand. He described the scene in a June 30 letter to his sister, Ruth, which was excerpted in a 2010 story in the Jeffersonville, Indiana News and Tribune.

I take a pencil stub and some wet paper and hurriedly describe the mass of wreckage, tentatively locate the fighting, notice the wonderful absence of enemy aircraft, then back into the water to a British landing craft pulling away. I crawl aboard, hurriedly asked the captain to take the story to [Reuters]. Then over the side and back into the water. Not the first guy to swim for France, but maybe the first to swim for it twice.

As was the case with several other correspondents in the logistical chaos of the day, his story never made it back to London for transmission.

His first widely published byline came six days later, chronicling the visit by Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and other dignitaries to the Normandy beachhead. But Wilhelm would be in the papers plenty from that point forward, entering Paris with Allied troops on Aug. 25, covering the fighting in the Hurtgen Forest in the fall, and reporting from the midst of the Battle of the Bulge in December.

Attached to the U.S. First Army, he described the fighting around Monschau in the opening days of the German counteroffensive in a Dec. 20 story:

I am writing this story in a barn behind a Belgian hunting lodge. On the well-paved roads along which I have just traveled from one end of the front to another there are no road blocks and entrenched positions such as the Americans encountered when they pushed forward in this area. Accordingly, Rundstedt’s tanks are able to whip here, there and everywhere until the Americans can blunt the spearhead.

This sort of thing leads to surprising small actions in areas where none is normally expected. In a small town a minor battle of this type was won against German paratroopers by rear area troops, who left the streets filled with German dead. The difficulty of this type of fighting is shown by the number of dead Germans found in civilian clothing. In this sort of battle one cannot positively identify the enemy until he attacks.

Following the war, Wilhelm joined the Chicago Sun as a foreign correspondent before moving to the new McGraw Hill World News cooperative, which covered postwar business news for a variety of publications.

In January 1968, Wilhelm moved to academia as director of Ohio University’s School of Journalism and later that year became the founding dean of the university’s College of Communications. He held that role for 15 years before stepping down but continued teaching for five more years before retiring in 1988.

During his time at Ohio U., he worked to ensure the legacy of his fellow World War II correspondents. In 1981, he organized a reunion that attracted many journalists we have written about here, including Jack Thompson, Gladwin Hill, Wright Bryan and Ann Stringer.

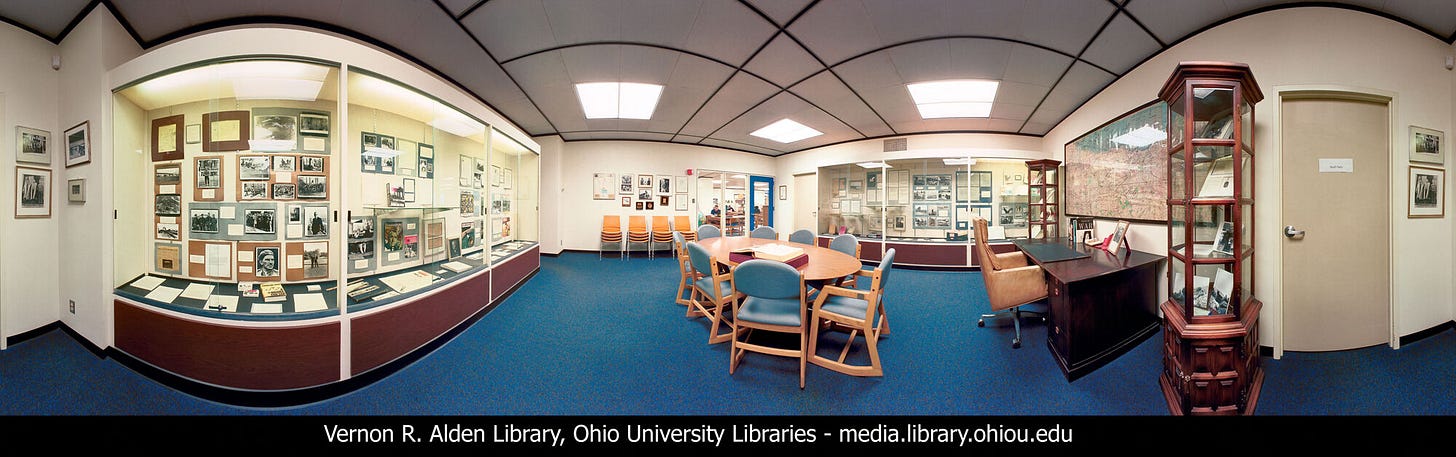

One other attendee was responsible for Wilhelm’s signature contribution to maintaining his peers’ legacy, though. Kathryn Ryan, widow of the late correspondent and author Cornelius Ryan, that year donated her husband’s papers to Ohio University. Researchers can now travel to Athens and examine the building blocks of Ryan’s seminal trilogy: The Longest Day, A Bridge Too Far and The Last Battle.

Entrusting Ryan’s invaluable files to Wilhelm seemed only fitting. The men’s relationship dated to the war, and in 1944 the Irishman had introduced Wilhelm to the woman he would marry, Red Cross nurse Margaret Maslin, while the three of them were in France.

She went by Peggy, and she was the one who filled in the details of her husband’s death on the 50th anniversary of Operation Overlord after a Columbus Dispatch reporter called.

“It was ironic that it happened on D-Day because he had been there on D-Day and he had been looking forward to the observance,” she said. “He liked to tell old war stories.”

Dr. Wilhelm was a friend, I was but a young student fresh out of the Army. Dr Lobdell was my son’s god father. I spent a lot of time working in the Conny Ryan collection when it first arrived. Had to leave as I was offered a dream position in Washington DC.

My daughter got to take part in the original dedication of Normandy Park…at age five.