You have seen Joe Rosenthal’s legendary photo of the American flag being raised over Mount Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945, the fifth day of fighting on Iwo Jima. If you’re familiar with the backstory, you’ll know that Rosenthal’s photo was of the second flag raised by the Marines that morning.

T/Sgt. Keyes Beech was the first journalist on the scene that day and would share the stories of the men involved in raising both flags.

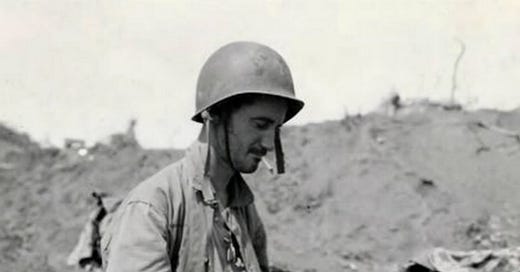

A Marine Corps combat correspondent attached to the 28th Regiment, 5th Marines, Beech landed on Iwo shortly after the first waves went ashore on Feb. 19 with an eight-pound portable typewriter strapped to his back and a .30 carbine in his hand.

A little over a week later he would write to his sister Mabel in Florida, and excerpts from the letter were printed in the St. Petersburg Times:

As I left the Higgins boat I expected to see the bodies of our dead and wounded on the beach. To my intense surprise and bewilderment I saw not one wounded Marine. …

All that day I kept thinking, ‘This is too easy,’ and it was, for all hell was breaking loose in the direction of Suribachi and to the north. Only I didn’t know it that first day. You only know what you can see and when the mortars and snipers are busy you don’t see much. You keep close to your foxhole.

That was a principle that would serve Beech well over the course of three wars.

William Keyes Beech was born Aug. 13, 1913 on a farm in Giles County, Tennessee. He went by his middle name, which rhymed with “size”.

His family moved to Florida around 1922 and it was there that he got his start in journalism as a teenager, working as a copy boy for the St. Petersburg Evening Independent before beginning to report and write stories himself.

His father and his older brother, Walter William Beech Sr. and Jr., died within six months of one another in 1936, and Keyes moved to Akron with his wife Mildred the following summer to join the Beacon Journal staff as a reporter.

Beech covered a variety of topics during his time in Akron, including a spring 1941 tour of U.S. military bases around the South, before leaving the paper in December 1942 to join the Marines. He went through the obligatory boot camp at Parris Island before reporting to Washington to be indoctrinated as a combat correspondent for the Corps.

Sgt. Beech shipped out to the South Pacific in the summer of 1943, and saw his first significant action at Tarawa in November. His proud former employers at the Beacon Journal stripped his first dispatch from there across the top of the front page of their Dec. 8 editions. It began:

Three of us stood in the forward gun turret of a troop transport off Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands and chortled with unholy glee while our warships and aircraft covered Japanese shore positions with a blanket of fire and lead.

Suddenly there was a swishing sound and a burst of spray 50 yards off the port bow. Marine Platoon Sgt. Walter S. Kremers, 24, of Bend., Ore., and I looked at each other in plain astonishment.

“Would you believe it!” he exclaimed with flaming outrage. “They’re shooting at us!”

Beech’s later dispatches were not as jocular, as he noted the “feel and smell of death” present on Betio after four days of intense combat.

Of the countless coconut palms, only a few remained standing, and these were ripped and torn by shell fire.

A few feet from a Japanese bunker — and open-topped breastworks — there was a flame-seared Marine tank. Somebody told me the crew had escaped after knocking out the enemy position.

The Jap dead lay in heaps in and just outside the pillboxes and bunkers. Rather than surrender, many had placed the muzzles of their rifles against their heads and pulled the triggers with their toes.

Most of the Marines who died lay on the beaches, their bodies washed by the waves.

Beech would rotate home on leave the following spring before returning to the Pacific later in 1944. The following February he would produce his best-known work of the war at Iwo Jima.

Beech was in the midst of the action on Mount Suribachi, to the extent that an early report said he was one of the men who had raised the flag. Fellow USMC combat correspondent Sgt. Henry A. Weaver III, writing from aboard a ship, said in a story distributed by the Associated Press that Beech was “among the first men to climb the heights to raise the colors” — an erroneous tidbit that made it onto the front page of the Beacon Journal.

Upon returning to the States a month later, Beech would tell the paper’s Washington correspondent Charles C. Miller: “Hell, no, I didn’t raise that flag. I was 50 feet away ducking grenades.”

In fact, Beech wrote multiple times about 20-year-old Platoon Sgt. Ernest I. Thomas, who was one of the men who raised the first flag and would be killed a few days later. Beech would type out a brief story about his death, saying it was not easy for him to write. “But one thing helps. From where I sit, I can see the flag over Suribachi.”

Beech would file several stories from Iwo over the next few weeks that would eventually make their way into U.S. newspapers. After the impact of the Rosenthal photo became clear, though, he and another combat correspondent on the scene, Jim Lucas, were ordered back to Washington in late March with an assignment to collaborate on a quick-turnaround book: The U.S. Marines on Iwo Jima.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt made identifying the Marines in Rosenthal’s photo a priority, and Beech would write the story listing the six men’s names on April 8. The initial IDs were provided by Pfc. Rene Gagnon, who said the survivors among the men in the photo were himself, Pfc. Ira Hayes and Navy Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class John Bradley.

Hayes and Bradley were sent to join Gagnon in Washington to drum up support for the Seventh War Loan Drive. The trio met with new President Harry Truman at the White House on April 20 and began a two-month tour of war bond rallies in early May. (More than 70 years later, the Marine Corps determined that Bradley and Gagnon had not actually been among the group that raised the second flag.)

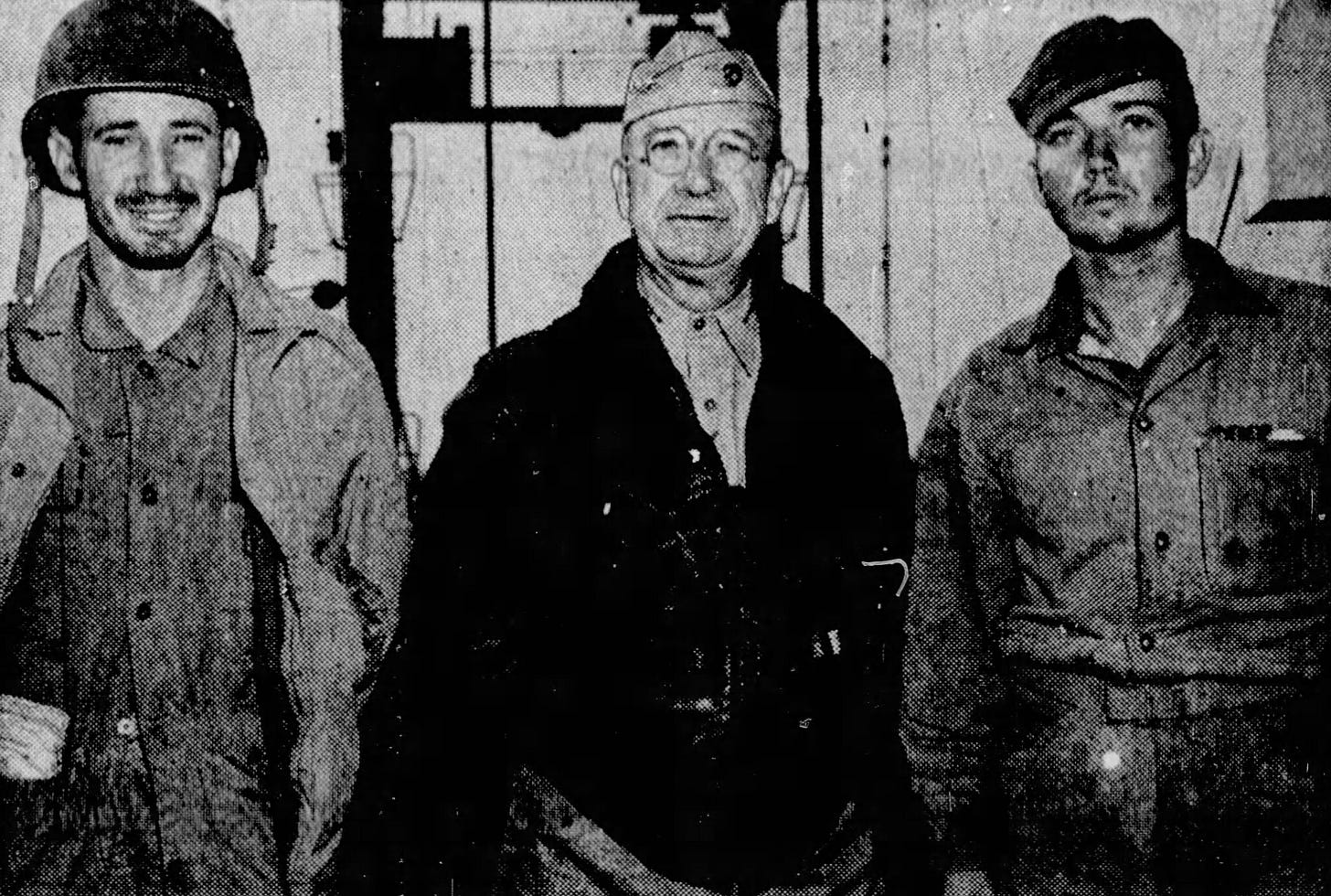

Keyes Beech went with them, serving as the leadoff speaker as they made their way around the country raising money for the war effort. He had his stump speech down pat by the time the tour hit Akron on May 17.

“Nobody out there is going to stop fighting just because people at home don’t buy war bonds,” the Beacon Journal quoted him as telling the audience. “But they are going to know whether or not the Seventh War Loan is successful and will know whether or not the people at home are in back of them.

“You people here are just asked to invest your money at a profit. All the fellows out there are asked to do is to die, and there’s not a lot of profit in dying.”

After leaving the Marines following the end of the war in the Pacific, Beech joined the staff of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, initially reporting from Washington before arriving in Hawaii in January 1946. The following summer, he was “loaned” to the Chicago Daily News foreign staff and embarked on a tour of Japan.

He joined the Daily News permanently in August 1947 while still in Tokyo and would remain with the paper until it closed in 1978. It was there that he did the work for which he is best known — writing about the wars in Korea and Vietnam.

In 1951, he was one of six correspondents who shared the Pulitzer Prize in international reporting for their coverage of the fighting in Korea.

Three years later he was in Hanoi writing about the emerging conflict in Indochina, the start of two decades of coverage of Vietnam. His lead the day Dien Bien Phu fell to Communist forces said the defeat “will probably go down in history as one of the greatest military — and political — blunders since the Charge of the Light Brigade.”

Tokyo was Beech’s home base for the better part of his three-decade stint with the Daily News, though he set up shop in Saigon for several years in the mid-1960 and covered that conflict through the bitter end. He was among those who boarded a helicopter on the roof of the U.S. embassy there on April 29, 1975, which he would later call “the most humiliating day of my life.”

Struggling financially, the Daily News closed the last of its foreign bureaus in 1976, a decision that brought Beech back to Washington. But he wasn’t ready to give up covering Asia.

In January 1979, he joined the Los Angeles Times as their Bangkok bureau chief and wrote about the region for three more years. He filed his last story from Hong Kong in March 1982, noting that “today’s Asia is more interested in making money than making revolution.”

One other observation in his farewell piece still rings true: “The ‘lessons’ of Vietnam can, in my view, be distilled into one. Never get into a war unless you intend to win it.”

Beech returned to the D.C. area, making his home in Bethesda, Maryland. He still wrote occasionally, including a widely distributed piece on Emperor Hirohito for the Washington Post in 1989, but his health began to decline.

On Feb. 15, 1990, Beech died of emphysema at Washington’s Sibley Memorial Hospital. He was 76 years old.

thanks for posting this. Keyes Beech was my father. Your reporting has filled in a few holes in his history I was unaware of. Do you mind sharing how you uncovered this information? Thanks

Hi, Really interested in your post and the work you've done. I've recently completed a biography of Keyes Beech, to be published by Texas Tech University Press. I'm familiar with the photo you have used of Beech on Iwo but have so far not tracked down the source. Do you know what that is? Thank you.