Liberating Caen: The unbroken spirit of 'war-tortured' French civilians

The renowned CBC correspondent Matthew Halton was among several reporters who entered what remained of Caen with British and Canadian troops on July 9, 1944.

A common thread runs through the reports filed by the men on the ground that day -- a sense of awe at what the historic French city, and more importantly its people, had endured in the nearly five weeks the Allies had fought to dislodge the German occupiers. Looking back on the day in a 1956 CBC television program, Halton summed it up this way:

Our high command had planned and hoped to take that city of Caen on D-Day, but in fact it was a month later before we got it. And in that month, the people of Caen had learned the meaning of hell.

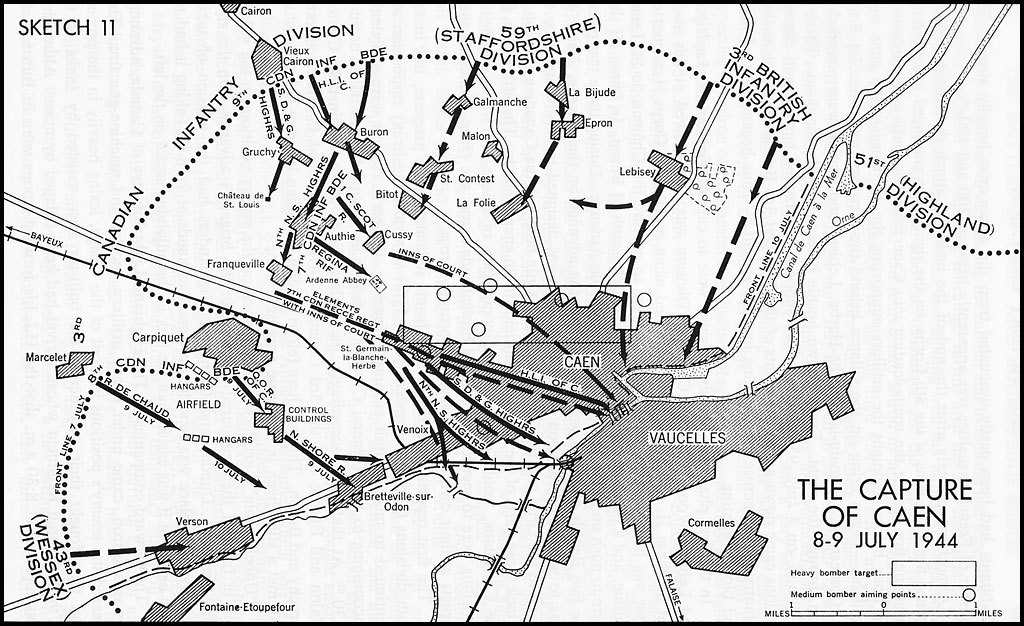

Caen was indeed a D-Day objective of the British 3rd Infantry, which landed on Sword Beach, but the city proved an elusive prize. While the Allied invaders established a foothold and drove inland from the five landing beaches across the Cotentin Peninsula, they failed in repeated attempts to secure Caen over the next few weeks.

On July 4, the 3rd Canadian Infantry attacked Carpiquet, about three miles to the west of the city, and captured it the following day. That set the stage for yet another attack on the primary target, and the Allies were ready to make this one stick. Late on July 7, RAF bombers began a three-wave raid on the city's defenses, with naval guns and field artillery joining in after the aircraft had cleared the area.

Joe Illingworth, war correspondent for the Yorkshire Post, described the scene:

Just before 10 o'clock last night I saw the sky before Caen fill suddenly with puffs of smoke that looked no bigger than a man's fist, and all at once the air seemed to rock as if it were something solid that was being beaten with a flail. Then I saw the first of our heavy bombers roaring in out of the setting sun. It was an extraordinary sight.

The bombers flew in perfect formation at about 8,000 feet, and though the German anti-aircraft gunners tried with savage despair to fight them back they still went on. And more followed.

I looked back all along the sky to the rose-coloured clouds in the west. There were bombers all the way. The battle for Caen had begun. All Normandy seemed to be watching and listening and to be holding its breath. The people came out of their houses and stood in the streets; the soldiers came out of their tents and stood in the fields. ...

It was at once a very beautiful and very terrible spectacle. Soon Caen was giving off dense clouds of acrid smoke. Then the fires began to burn. They burned in the streets of Caen all night.

The barrage did significant damage to the city itself, and British and Canadian ground forces attacked from the north and west beginning early July 8. They hopscotched through small villages on the outskirts, driving the Germans south, and found themselves on the edge of the city by evening.

German commanders on the scene decided to pull their forces back that night, opening the door for the Allies to swoop in at last in the morning of July 9 even though scattered pockets of resistance remained in the bombed-out streets. "Caen was in shambles and nothing could move through the city except infantry and bulldozers," wrote Roger Greene of The Associated Press.

Wrote Mark S. Watson of the Baltimore Sun: "That aerial bombardment clearly broke the resistance of the German Panzer units which had been blocking the northern approach to Caen, but unhappily it also broke a good deal of Caen as well."

Despite what he described as "bitter street-fighting" ongoing in the city, Charles Lynch of Reuters described a top Canadian officer "almost dancing with joy" over the triumph.

By the afternoon of the 9th, Caen was in Allied hands, with the bulk of the German presence now south of the Orne river (and not to be dislodged for a couple more weeks). Vichy radio confirmed the change in hands that evening, saying the city had been "evacuated" by the Germans.

Given a few more hours to explore the ruins, though, it was Lynch who summed up what would become the theme for correspondents reporting from the scene:

The story of Caen is not the story of the soldiers who took it or the soldiers who have been driving from it -- it is the story of the people whose lives have been one long nightmare since the night of June 6 when the city was first bombed and they knew that war had come to Normandy.

"Looking into their faces, they all seemed either young or old," Associated Press correspondent William Smith White observed as he entered Caen.

Above all, they were grateful. Wrote Doon Campbell of Reuters on Monday, July 10: "The people of Caen are dressed in their best and most colourful Sunday clothes to-day, and have gathered in thousands to see the flag of liberation hoisted from a lamp-post outside the Town Hall." He continued:

I have never had a more sincere welcome. Old women and little children come running into the middle of the road to say "Bonjour," and shake you by the hand. They have got a hand-shaking obsession. The tiny ones do not know what the gesture means but they do it.

There is much ruin and devastation. It is worse than London's East End. It is like parts of Naples -- huge gaps torn in high multi-storey tenements, shattered roofs, broken windows. But the people stand behind the glassless windows. They cheer and wave excitedly. They cry words of welcome. It is the greatest moment of their lives.

Both Matthew Halton, this time in a written dispatch, and Christopher Buckley of the Daily Telegraph led their accounts with accounts of townspeople singing the French national anthem, a la "Casablanca." Wrote Buckley:

They are signing the "Marseillaise" in the square outside the Lycée Malherbe, where I write these lines. They are singing it at this moment, these courageous, haggard, war-tortured French citizens.

The song takes on a new significance. It is the most profoundly moving experience I have known in five years of war. For to-day Caen is coming to life once more; it is an indication of the eternally renascent spirit of France.

I could not have believed that in the ghastly cemetery of a town into which I penetrated yesterday so many civilians would be alive, so many who have suffered night and day under bombing and shellfire could have received us with such enthusiasm. The spirit of these people is unbroken. They must have suffered as much in the past month as the people of any town in the course of this war, but there is nothing that is crushed in their demeanour.

This kind of scene was new to the liberators, and to the correspondents sending the news back home. It would of course become more familiar as the Allies swept the Germans back toward their homeland, with scenes like this repeating in Paris, in Holland, in Belgium.

But this first outpouring of unadulterated gratitude from a liberated people left the observers stunned, just as the destruction inflicted by the liberators clearly left a bad taste in some mouths. Mark S. Watson of the Baltimore Sun, clearly a student of architecture and history, filed hundreds of words back home that day, recounting in painstaking detail what had been lost to free Caen.

He concluded his report this way, preemptively agonizing over the inevitable destruction still to come:

These are fine people, of magnificent spirit. While they live France will not die.

But one ends a day in Caen with a feeling of intense pain that such a people and such a noble city must be pounded by war's deadliest instruments in order to dislodge from their midst those savage fighters who have lodged among them.

There are a great many noble cities between the Allied armies and the Rhine.