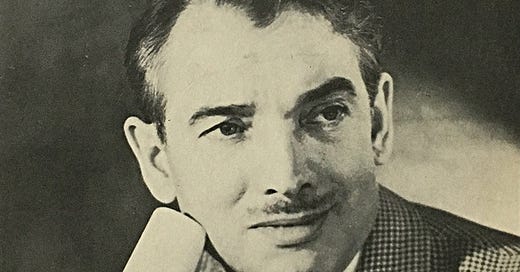

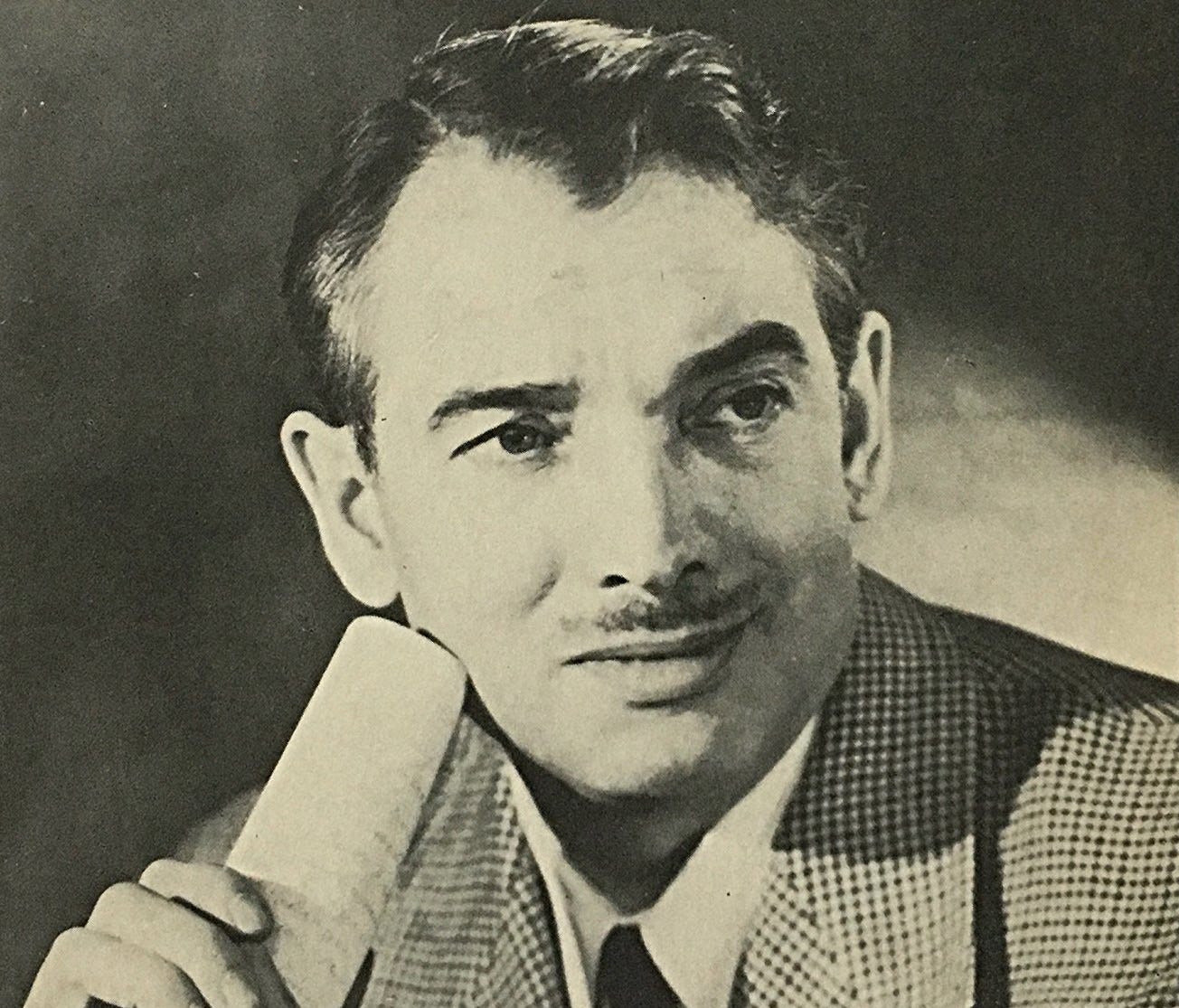

Lionel Shapiro needed a decade to find perspective on his D-Day experience

As he sat down to write perhaps the most important story of his life to date, Lionel Shapiro knew he didn’t have all the raw material he needed — and he shared that with his readers right up front:

History should be written by one who can sit quietly and look reflectively into the past; by one who has before him all the facts and the figures, who can count the sacrifice and measure the victory. I cannot do this.

I am sitting amidst the thunder of the desperate present. The new battle of France is 10 days old; it has hardly begun. My typewriter is set up in the living room of a broken French dwelling close to the battle front before Caen. The walls shudder to the incessant boom of big guns; fighting planes are roaring low overhead; the whine of our naval shells lends an eerie overtone to this macabre symphony. History is standing astride these rolling Norman fields and resolving its own direction for perhaps a thousand years to come. We mortals who sit below can only be awed by its mighty presence.

But if I cannot write world history in its proper perspective, perhaps I can write a personal version of Canadian history as it was unfolded before my eyes during these last flaming days, because between the little seaside town of Bernieres-sur-Mer and the Caen battle front Canadian troops have written an immortal story.

So began the 36-year-old correspondent’s story in the July 15, 1944 edition of Maclean’s, the Canadian newsmagazine. The piece, written several days after the invasion, explored Shapiro’s time alongside Canadian troops in the days leading up to Operation Overlord, from the phone call he received in late May to report to a staging area for correspondents, to the uneasy wait aboard a ship in the English Channel, and finally his trip ashore at Juno Beach with the 3rd Canadian Division.

Born Feb. 12, 1908, in Montreal, Lionel Sebastian Berk Shapiro was a natural writer, even if he continued to find himself in situations he considered less than ideal. He began his journalism career as a sportswriter at the Montreal Gazette in 1929, although “he was the least athletic of sports writers and sports in fact interested him little,” as the Montreal Star wrote in an editorial following his death. The same piece noted that when it came to covering the war, he was far from gung-ho: “he suffered more than most from nerves and worry.”

Shapiro’s true passion was the theater, and he tried his hand as a playwright on occasion but couldn’t make it pay the bills. As it turned out, though, the experiences he endured as a war correspondent would end up as the foundation of his best-remembered work.

However nervous Shapiro may have been in war zones, he was not the type to shy away from a challenge. His father had died when he was 2 years old, and Lionel lost both of his brothers to tuberculosis within the span of a year when he was a teenager.

He earned a psychology degree (with honors) from McGill University in his hometown but opted to go into journalism rather than academia, as he originally had intended, after working at the McGill student newspaper. About five years into his stint at the Gazette, he escaped the sports department for a plum position as the paper’s New York correspondent, writing a regular column called “Lights and Shadows” under a byline that read L.S.B. Shapiro. In 1940, he moved to Washington to serve as the Gazette’s White House correspondent, taking the column name with him.

In August 1942, he flew to London and set up shop at the Savoy Hotel to begin covering the war full-time. He had spent a few weeks in England in the fall of 1941, but this time he would settle in and cover the war “for the duration,” as the newspaper put it.

Shapiro would cover Canadian troops in the Sicilian campaign in 1943 and was attached to Gen. Mark Clark’s headquarters ahead of Operation Avalanche, the Allied invasion of mainland Italy at Salerno. The night before the attack, Clark summoned Shapiro and three other correspondents to his cabin and laid out his plans for the following day. Shapiro would make it ashore around noon on Sept. 9, some eight hours after the initial landings.

“On this sunbaked beach a gallant Anglo-American force has punched a big hole into the centre armor of Hitler’s ‘Fortress Europe’ and is thrusting through to its heart,” he wrote.

About two months after those initial landings, Shapiro composed a series of in-depth stories about the Salerno campaign. Impressed by the correspondent’s work, the North American Newspaper Alliance made Shapiro an offer he couldn’t refuse and lured him away from the Gazette.

Writing regularly for the NANA syndicate, he was on hand for the Allies’ next great incursion into Europe nine months after landing at Salerno. While his initial stab and describing the D-Day scene for Maclean’s may have left him unsatisfied, he would come back around to the topic eventually.

Shapiro remained in Europe following the war, serving as a foreign correspondent for NANA. A connection at the syndicate led to an introduction to a publishing executive, who thought Shapiro should try using his time as a war correspondent as a jumping-off point for a novel.

His first effort was called “Sealed Verdict,” which published in the fall of 1947. It was set in postwar Europe, as was his second novel, “Torch for a Dark Journey,” which came out in 1950. Five years later came his signature work, “The Sixth of June,” the story of an Anglo-American love triangle playing out mostly in London ahead of and into the Normandy invasion.

He was about half-finished with the book in October 1954 when 20th Century Fox bought the film rights for $75,000 (more than $800,000 today) — not knowing yet how it might end, because Shapiro himself hadn’t yet figured it out. Their faith was rewarded as the finished product became a best-seller and Book of the Month Club selection, and was awarded Canada’s prestigious Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction for 1955.

The film version, “D-Day the Sixth of June,” was released in May 1956 and starred Robert Taylor, Dana Wynter and Richard Todd. (Todd, a British airborne trooper during the war, would later feature in another film based on a book by a war correspondent who covered D-Day, Fox’s 1962 adaptation of Cornelius Ryan’s epic “The Longest Day.”)

Though “The Sixth of June” was not autobiographical, Shapiro readily acknowledged in an interview with the Ottawa Citizen that the novel was underpinned by memories of his glory days.

I am one of those who really hasn’t lived since then — or lived before then. … And psychologically I would say that the intensity I put into this book was a reversion to youth. I am 47 now, where you begin to feel well into middle age, and I think this was an urge to get back to my greatest days, which were my war days. I always thought I would write a novel about London then, and certainly D-day, but I wanted almost 10 years for a proper perspective.

It was a novel, not a newspaper or magazine story, but Shapiro finally had the context he knew he had been missing in those days immediately following June 6, 1944.

Though Shapiro continued to work for NANA and produce magazine pieces, he was well-established as novelist by this point. He told an interviewer during the publicity tour for “The Sixth of June” that his next book was due to Doubleday on May 1, 1957. It never arrived.

Shapiro was diagnosed with cancer that year and underwent surgery. It was a short-term fix, as the disease returned in 1958. His mother also was ill at the time of the recurrence and he feared she wouldn’t survive if she knew he was gravely ill. So rather than letting his mother know he had checked into Montreal General Hospital in the summer of 1958, he told her he was in New York at the Hotel St. Moritz, where he regularly spent time working on his novels.

While Shapiro’s mother remained in the dark, he received get-well wishes from the likes of Bernard Montgomery, Harold Alexander and Harry Crerar. In the final days before his death on May 27, 1958, reported his friend and Maclean’s editor, Ralph Allen, Shapiro was unable to write using a typewriter or a pen, so he shared some thoughts into a dictaphone at his bedside, a reporter to the end.

Allen concluded his Maclean’s tribute to his friend this way:

In his years of good health and prosperity he was one of the most notorious and chronic worriers who ever set foot on earth. A hangnail, a cold in the head, a luke-warm letter from an editor, or a drop of fifty cents in the stock of Imperial Oil or Royal Bank could set him off on a lament of several days and positively Biblical gloom. But he was much too proud to let himself be frightened by anything really dangerous.

The last time I said goodbye to him he said simply and calmly: ‘This is okay. Nothing is hurting much, I can handle it.’ And so he did — handled his life well and handled his death well and left them both with dignity.