Massacre at Malmedy

Between the logistical difficulties of transmitting from the field and the vagaries of censorship, it could take days or even weeks for World War II correspondents to get their stories from the front published back home. When Allied forces had news they wanted to get out, though, the apparatus was remarkably nimble.

So it was that newspapers across the United States, Canada and beyond set aside space on the front pages of their Dec. 18, 1944 evening editions for the stunning story Associated Press correspondent Hal Boyle had filed from Belgium the day before. It began:

AN AMERICAN FRONTLINE CLEARING STATION, Belgium, December 17 -- Weeping with rage, a handful of doughboy survivors described today how a German task force ruthlessly poured machine gun fire into a group of about 150 Americans who had been disarmed and herded into a field in the opening hours of the present Nazi counter-offensive.

Boyle's initial report on what would come to be known as the "Malmedy Massacre" quoted two American enlisted men who had survived by playing dead, then fleeing into the woods when the bulk of the German force had moved on.

The specific location of the incident -- a crossroads in tiny Baugnez, Belgium about two and a half miles southeast of Malmedy -- was not mentioned in the story, nor were any specifics about the units involved. This was standard procedure under the censorship measures in place, particularly given the fluid nature of the fighting in the opening days of what would come to be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

But this was a story the U.S. military wanted disseminated, and the devastating account offered up by T/5 William B. Summers of West Virginia spoke for itself. Summers was in a convoy composed mostly of members of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion that encountered elements of the 1st SS Panzer Division led by Joachim Peiper at the Baugnez crossroads shortly after noon on Dec. 17.

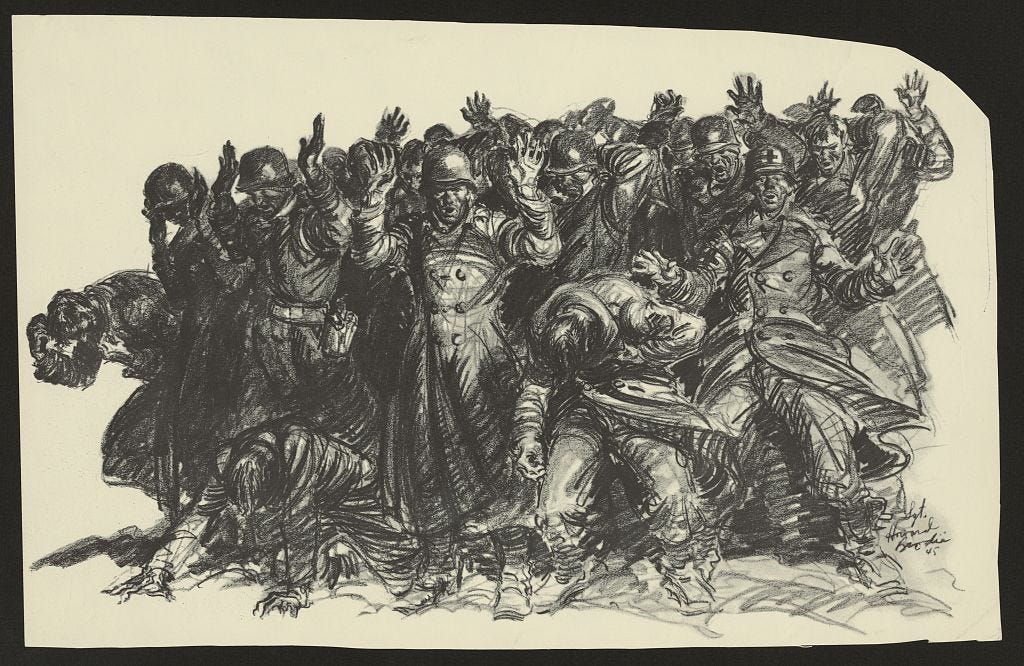

"We were just moving up to take over a position at the top of the hill and as we got to the road intersection they opened up on us," said Summers. "They had at least 15 to 20 tanks. They disarmed us and then searched us for wrist watches and anything else they wanted.

"I guess we were lined up along that road for a full hour. Then they stood us all together in an open field. I thought something was wrong. As we were standing there one German soldier moving past in a tank column less than 50 yards away pulled out a pistol and emptied it into our fellows."

A grimy soldier sitting in the little room here with Summers ran his hands through mud-caked hair and broke into sobs. There were tears in Summers' eyes as he went on:

"Then they opened up on us from their armored cars with machine guns. We hadn't tried to run away or anything. We were just standing their with our hands up and they tried to murder us all. And they did murder a lot of us.

"There was nothing to do but flop and play dead."

That desperate tactic worked for Summers, but not for everyone. "We had to lie there and listen to German non-coms kill with pistols every one of our wounded men who groaned or tried to move," he told Boyle.

The story struck an immediate chord not just with readers back home, but also with troops on the ground who already had heard rumors of the atrocities.

In a story datelined Dec. 19, Boyle's AP colleague Tom Yarbrough wrote: "The story of German brutality in slaughtering nearly 150 American prisoners in cold blood Sunday afternoon near Malmedy, Belgium, has fired First Army troops with a new measure of hate as they face the Nazi counter-offensive."

Yarbrough's follow-up included independent confirmation of the shootings provided by two more survivors, Pfc. Peter Piscatelli of New York and Pfc. L.M. Burney of Arkansas, whose accounts matched the details in Boyle's first report.

The following day, Dec. 20, First Army filed an official report on the massacre to Washington after interviewing approximately 15 men who had escaped the carnage at the crossroads. A United Press account of the report echoed Yarbrough, noting that "the story has spread up and down the entire First Army area, giving cold determination to the Yanks' desire to finish off the attacking Germans."

Around this time, CBS correspondent Richard C. Hottelet first reported Germany's use of captured U.S. jeeps filled with English-speaking troops wearing American uniforms attempting to talk their way through Allied lines.

Word of that tactic also had spread quickly among U.S. forces, and when viewed alongside the massacre of prisoners in the same operation it was evident that the Allies were facing an increasingly desperate enemy.

The news continued to reverberate as the fighting raged across Belgium and Luxembourg. An AP story filed from Malmedy on Dec. 28 reported that a German motorcycle courier who had been ambushed the day before was carrying pictures of "burning American equipment, American prisoners and dead, and triumphant SS troops," including a photograph of a group of dead American soldiers lined up in front of German guns.

The following day, U.S. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius announced he had filed an official protest via neutral Switzerland that German troops' actions at Malmedy constituted a "gross violation of the Geneva Prisoners of War Convention and the generally accepted international rules of warfare." The telegram demanded the German government punish those responsible and issue "the necessary orders to prevent the repetition of such an occurrence."

"Officials here are not at all optimistic about accomplishing anything with the protest to Berlin," an Associated Press correspondent in Washington wrote. "Nevertheless, it will become part of the formal international record of war and stand as a matter for which the Germans will be held to account when victory is won."

While diplomats went through the motions in their world, some troops took matters into their own hands.

Postwar accounts include numerous mentions of units issuing "take no prisoners" edicts as a response to Malmedy, particularly when the prisoners were SS men.

On Jan. 1, 1945, men of the U.S. 11th Armored Division killed dozens of German prisoners in a field near Chenogne, Belgium, in a direct reciprocation of the Malmedy slayings. Gen. George S. Patton mentioned it in passing in his diary, but news of the incident never went public during the war.

On Jan. 14, 1945, nearly a month after the slaughter, American troops returned to the crossroads at Baugnez.

The German counteroffensive finally had been beaten back, allowing officials to make a safe investigation of the massacre site. Over the next two days, they would find more than 70 frozen bodies at the snow-covered site, and the spring thaw would eventually reveal about a dozen more.

Drawing upon the forensic investigation and the accounts of survivors, the Army's Inspector General released a report on the massacre in early February.

In a story filed Feb. 3, Virginia Irwin of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch laid out newly reported details of that scene and other reports of German atrocities. At Malmedy, she wrote, "one American medic got up from the bloody pile and defied the Germans while he gave first aid to a man from his own unit. The Germans stood calmly by until he finished the job, then shot both the medic and the man to whom he had given aid."

Irwin concluded the Malmedy section of her report:

The story of this slaughter pen needs no comment. The word "slaughter" needs no softening. The German refusal to respect the noncombatant medical corpsmen in the front ranks of this group of unarmed prisoners of war is, to use army nomenclature, "standard order of procedure" with the Germans. The Red Cross on a medic's arm, on ambulances, on hospitals, means little to the Germans.

The story remained in the headlines on and off through the final months of the war.

Some wounded survivors who had been sent back home told their local newspapers about their experience. The March 30 edition of the Park City Daily News in Bowling Green, Kentucky, ran a lengthy interview with Lt. Virgil Penn Lary, who was wounded in the foot during the encounter and had recently discarded the cane he had been using to get around.

Wrote reporter Jane Morningstar: "In preparation for his return to civilian life since he expects to be discharged at the expiration of his leave, and to divert his thoughts from the horror of his experiences, the officer enrolled this week for an accounting course at the Business University."

The obligatory hometown newspaper stories on the Malmedy victims often did not tie the death of a husband or son to the massacre family members undoubtedly had read about.

That was the case for T/5 Max Schwitzgold of Delaware, who you can read more about here. Reports of his death emerged Feb. 5, the day after Irwin's story ran, but there is no indication in the initial stories that he was a victim of the massacre, only that he had been killed Dec. 17 in Belgium.

American troops rolling across Europe and eventually into Germany never forgot about the killings. In mid-August, more than three months after Germany's surrender, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division discovered Joachim Peiper was among the prisoners it had rounded up as the war ended.

Writing from Nuremberg on Aug. 18, Wes Gallagher of the Associated Press reported Lt. Paul Haefner of Illinois had determined Peiper's identity as he was in the process of questioning prisoners. His superior, Maj. Henry Glisson of New York, reveled in the discovery:

Peiper had been hunted intensively by the entire American Army, which had been investigating the Malmedy slaying as the biggest atrocity of the war against American troops in Europe.

"Boy! We're sure glad we located that fellow," said Glisson, a former combat man. "He's the doughboys' No. 1 public enemy. We feel a personal interest in the case because the men killed once worked with the First Division."

Peiper denied any knowledge of the incident, but the Americans weren't buying it. "He is a damned liar," Haefner told Gallagher. "He knew about the slayings and knows exactly who did them."

Peiper and others in the German hierarchy were put on trial beginning in May 1946, charged with war crimes for their actions at Baugnez and similar killings of prisoners and Belgian civilians during the Battle of the Bulge.

On July 16, 1946, Peiper and 42 others were found guilty and sentenced to death. Two years later, Peiper's death sentence was one of the original 12 upheld by Gen. Lucius D. Clay after a review, but a separate commission subsequently recommended those men instead be sentenced to life in prison.

All of those sentences ultimately were commuted as well, and Peiper was released from prison in December 1956. He would spend the next decade protesting against being characterized as a war criminal, and eventually moved to France in 1972.

On July 14, 1976, about three weeks after a French newspaper reported his whereabouts, Peiper died when his house was set on fire and he was unable to escape. He was 61 years old.

William B. Summers was not the only survivor quoted in Hal Boyle's initial report on the killings. Lower in the story, Harold W. Billow of Mount Joy, Pennsylvania, told of men jumping up to make their escape from the lone Tiger tank left covering the scene.

"The tank opened up on us, but I don't think it got many that time," he told Boyle.

As of the 75th anniversary of the Malmedy massacre in December 2019, Billow was believed to be the last living survivor.

Still living in Mount Joy, the 96-year-old spoke to LancasterOnline.com about his experience. Among the scenes he recounted was the murder of the medic described in Irwin's report -- fellow Pennsylvanian Luke Swartz.

He also hadn't gotten over Peiper and others responsible not being held accountable: "To this day, he says if those who shot his buddies that day were lined up, he would have no qualms about shooting them."