Making Manzanar: The first internment camp

On March 21, 1942, just over a month after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the removal of those who might be deemed a threat from the West Coast, the first volunteers arrived at the Owens Valley Reception Center.

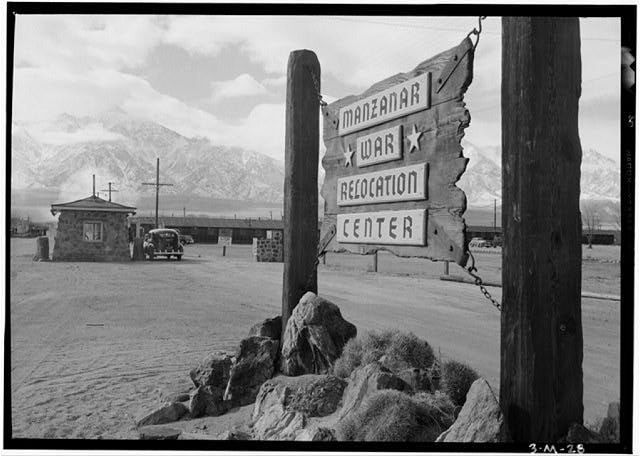

By June, the compound at the foot of Mt. Whitney would officially be designated the Manzanar War Relocation Center, the first of 10 such camps in which Japanese Americans would be interned during the war.

The word “Manzanar” meant nothing to most people in early 1942. It first appeared in the Los Angeles Times on March 6, with the first detailed coverage coming the following day under a front-page headline that read “Jap Roundup Plan Mapped.” This story and virtually all other news coverage in the growing weeks leaned on an announcement from Gen. John L. DeWitt, the San Francisco-based chief of the Army’s Western Defense Command.

DeWitt’s recommendations were the impetus behind Roosevelt’s order, and the general saw no distinction between citizens and non-citizens. Speaking to congressmen in San Francisco in April 1943, he would famously declare: “You can’t change a Jap by giving him a piece of paper. A Jap’s a Jap.”

Paranoia had run wild on the West Coast in the three months since the Pearl Harbor attack, with civilians and military officials alike convinced that the Japanese might attack the U.S. mainland via air or seaborne invasion at any time. Hand in hand with those fears were expectations that people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast were planning to aid said invasion or embark upon sabotage missions of their own.

Given the apparently widespread prevalence of that mindset, it’s little surprise that the primary concern among many Southern Californians when Manzanar was selected as a relocation camp site was its proximity to the Los Angeles Aqueduct, a key source of the city’s water. That was the sole focus of an editorial in the March 7 Los Angeles Times, which said residents should consider it their “patriotic duty” to take the Army’s word that the aqueduct would be adequately secured.

“The Army is doing its best to protect us,” the piece concluded. “The least we can do in return is to accept its efforts in good faith and do all we can to assist its program.”

Conspicuously absent from any coverage at the time: discussion of the internees’ civil rights. It simply wasn’t a consideration among the majority of the populace.

Instead, newspaper accounts focused on the impressively quick construction process and the acquiescent initial occupants. Tom Cameron of the Times reported from Manzanar for the March 20 edition:

First occupants of the concentration point will be 100 Japanese artisans — carpenters, plumbers, painters, electricians, etc. — who will arrive tomorrow to assist in construction of their wartime community.

An estimated 1,000 other Japanese — all volunteer deserters of the “no-alien’s land” that Southern California is swiftly becoming, are scheduled to arrive Monday.

Of the facilities themselves, Cameron wrote:

The center will furnish the Japanese with every comfort except the bright lights of Little Tokyo, from which many of them will come.

If American citizens in Japan are accommodated just one-half as considerately, they should be able to sit out the war in comfortable circumstances.

Not to mention tastefully decorated. James Lee’s report datelined March 22 for the San Francisco Examiner included this nugget:

After policing their quarters, the first act of pretty Nisei girls Gene Hashimoto and Rosemary Anzai was to tack upon the bare walls of their dormitories the striking picture of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, which they clipped from this morning’s issue of The Examiner.

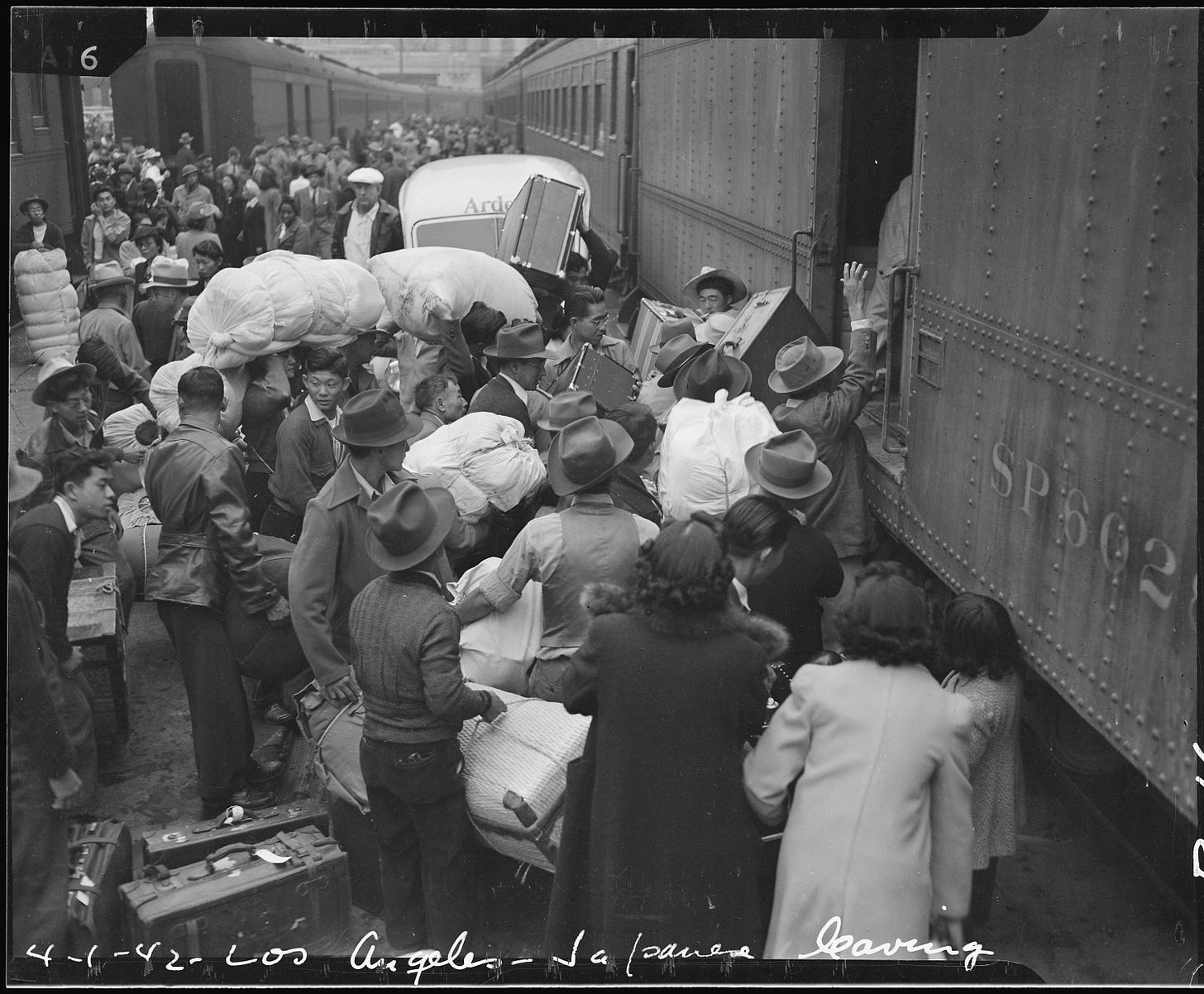

The initial convoy of internees from the Los Angeles area on March 23 was widely covered by the press. The headline over C.P. Corliss’ front-page story in the Pasadena Star-News reflected the general tone: “Japanese Cheerful On Way To Camp At Manzanar”.

The caravan began its 230-mile drive from the Rose Bowl in Pasadena a little after 6:30 a.m., “composed of cars of all sizes, shapes and makes, many obviously carrying baggage that exceeded the announced Army regulation of ‘just enough for personal needs.’ …

“A majority of the Japanese were in a cheerful frame of mind and looked on it as ‘a great adventure.’ All wore large cardboard tags, similar to shipping tags, fastened to serve as identification. on each tag was the evacuee’s name and home address.”

On their first morning in camp, Cameron wrote, the new residents “were served a breakfast of baked ham, hashed potatoes, stewed prunes, bread, butter and coffee.”

Associated Press correspondent Gladwin Hill wrote that he saw “no evidences of resentment among the emigres.

“Rather, there was a fatalistic comprehension of the problem confronting them, regardless of their personal patriotism, and hopeful determination for the future.”

That notion was reflected in the third paragraph of his story:

“You wait, we’ll make a little heaven out of it,” a Japanese voice proclaimed from the darkness.

They had no choice but to make of it what they could, for years to come.

C.P. Corliss made that clear in his dispatch to Pasadena the following day with this bit from camp manager C.E. Triggs:

When asked if a Japanese would be stopped by the Army sentry if he walked out of the camp the answer was “yes.”

“If the Japanese does not stop, what happens then,” someone queried.

“Ask the sentry,” was Mr. Triggs’ answer.

One look at the riot guns carried by the sentries and the way in which credentials of all persons entering and leaving the camp were examined gave one the answer. No credentials were issued to Japanese residents.

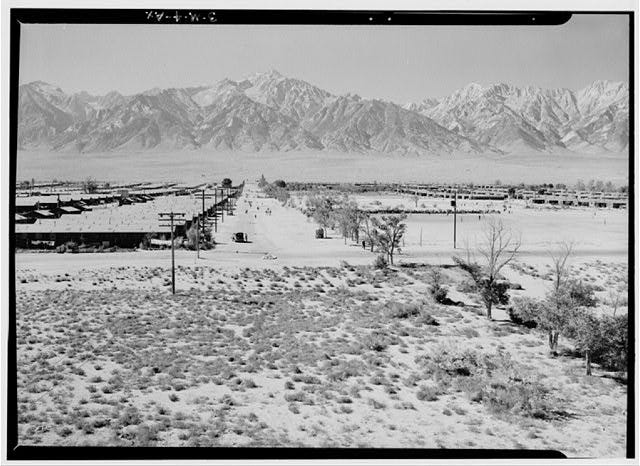

More than 100,000 would eventually be sent to the remote camps, with Manzanar’s population peaking at 10,046 in September 1942.

The camp closed on Nov. 21, 1945 and is now administered as a National Historic Site by the National Park Service.