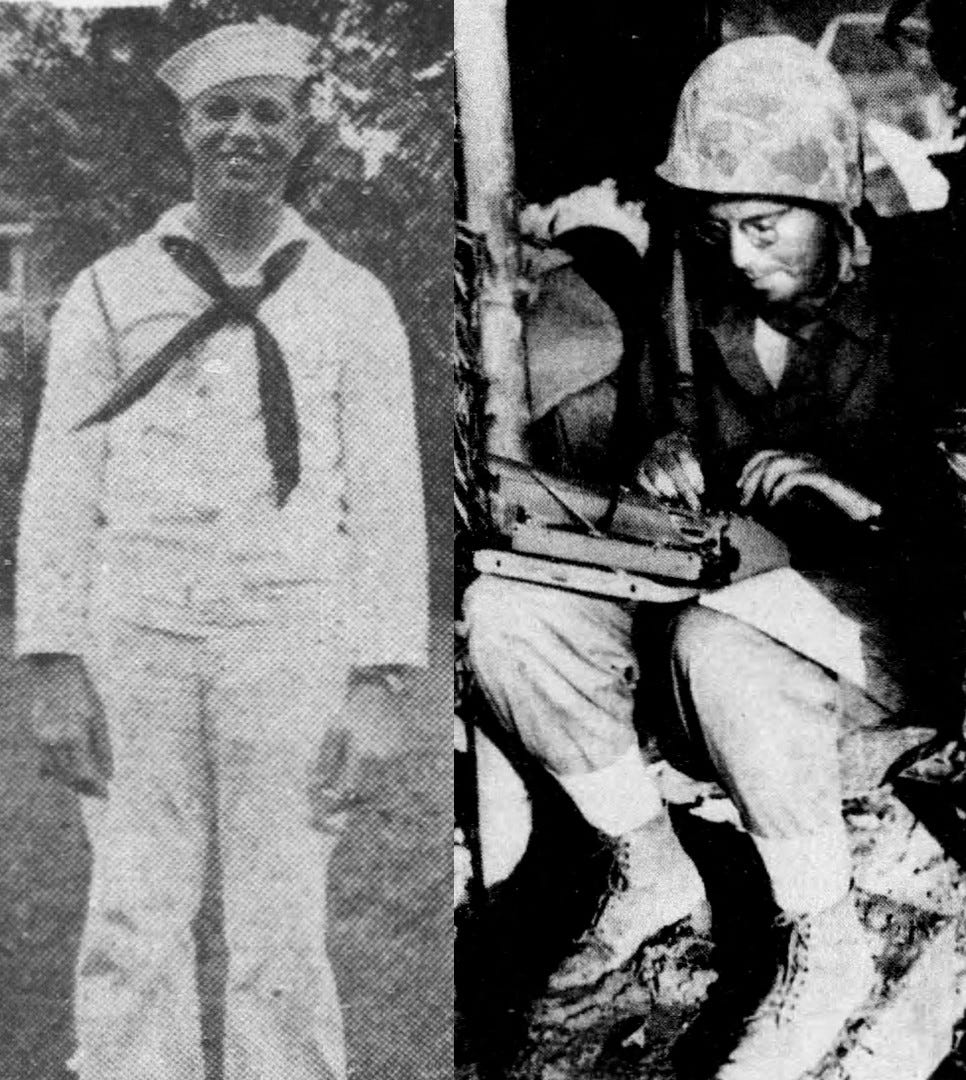

Martin Sheridan meets his savior

The October 13, 1944 editions of the Boston Globe featured one of the most remarkable stories of the war, and it just happened to be about one of the newspaper's own. Under the headline "Truth Stranger Than Any Fiction," war correspondent Martin Sheridan opened the tale from an unnamed ship in the Pacific:

Just before the movies tonight a tall, brown-haired, blue-eyed youngster stared at me for a while, then pointed and inquired, “You're Martin Sheridan, aren't you?” I nodded, whereupon my questioner introduced himself as EM1c Howard E. Sotherden, USN, of Mt. Hope Ave., Tiverton, R.I., and added, “I pulled you from the wreckage at the Cocoanut Grove fire.”

For nearly two years, Sheridan had wondered who had saved his life the night of November 28, 1942, when he had survived one of the deadliest fires in the country's history. Now, nearly 10,000 miles from Boston, he had his answer.

Sheridan had been handling publicity for the cowboy movie star Buck Jones at the time of the fire, and the pair had arrived at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub around 9:30 p.m. on November 28 along with Sheridan's wife Constance. About 45 minutes later, shouts of "Fire!" rang out in the club and everything suddenly went black, sparking a panic among the hundreds of patrons inside.

"I shall never forget the screams and cries of the trapped, the crash and clatter of overturning tables and chairs, the smashing of dishes and glasses," Sheridan wrote in 1957. "I began to choke from the mysterious fumes that swept the Grove, then sank unconscious to the floor atop the people in front of me. This happened in a matter of a few seconds."

Sheridan then briefly came to again but found himself unable to move.

I heard footsteps approaching and moaned as loud as I could. The footsteps came closer, then someone pulled me to my feet, walked me over wreckage and probably bodies to an exit. Clothes soaked from the fire hoses, I was propped in a chair outside in the below-freezing temperatures.

It was quite a battle to keep from falling off the chair. I saw there shaking, fighting to remain upright, unable to see because both eyes had puffed shut from the flames. My burned hands felt like the flesh was hanging from them. Finally, someone helped me into a taxicab. I remember asking where we were going. The driver said, “Massachusetts General Hospital."

Sheridan spent two months in the hospital recovering from his injuries, undergoing multiple blood transfusions and skin grafts, then endured two more months of outpatient physical therapy. Yet that made him one of the fortunate ones; 492 people died in the blaze, including Buck Jones and Sheridan's wife, Constance.

In mid-May 1943 Sheridan joined the Boston Globe's staff as a correspondent and eventually covered stories in North Africa and Greenland before shipping out to the Pacific in June 1944 after another round of plastic surgery on his hands.

On October 12, 1944, Sheridan was aboard the Fremont when the young sailor approached him. Howard Sotherden had been a Navy fireman stationed in Newport, Rhode Island, in November 1942 and was in Boston on a weekend pass. He walked out of a nearby bar around 11 p.m. and heard a policeman mention a fire at the Cocoanut Grove. Sotherden jumped in a taxi, raced to the scene, and asked police and fire officials at the site if he could be of any help.

He then saw firemen pulling bodies out of the club and went in himself. Sheridan was the third man Sotherden pulled out of the club. The sailor told the reporter he handed him off to a pair of policemen and one of the newspapermen on the scene looked at him and said, "Why, it's Marty Sheridan." The name didn't mean anything to Sotherden at the time, but he remembered it. As he told Sheridan aboard the ship:

"A few days ago one of the boys in the crew told me Martin Sheridan, war correspondent for the Boston Globe, was looking for New England men. That name stuck in my mind and tonight, while I was carrying the films from the film locker to the movie projectors, I recognized you speaking to someone outside the wardroom. Your face was familiar, and I stared at you, trying to recall where I had seen you. A few minutes later, when I was playing phonograph records over the loudspeaker before the picture, I spotted you again and asked whether you were Marty Sheridan. It's certainly a small world."