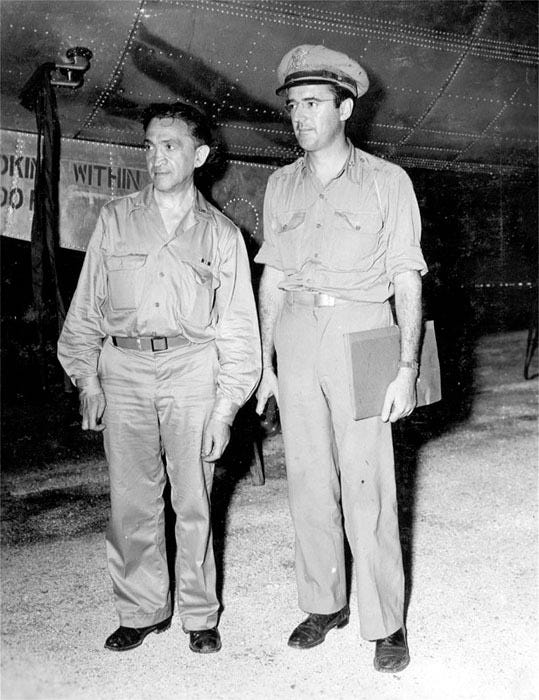

William L. Laurence witnesses the bombing of Nagasaki

On August 9, 1945, William L. Laurence was one of 13 men aboard the B-29 The Great Artiste, one of three Superfortresses on a mission to Nagasaki, Japan.

Laurence was a Lithuanian-born journalist who had spent years covering science topics for The New York Times and other outlets. As the Manhattan Project neared conclusion in the spring of 1945, U.S. Army officials invited Laurence to join the operation in a public relations capacity.

Serving as the official historian of the atomic bomb project, he wrote press releases and documented the work being done by scientists in the New Mexico desert. He was present for the "Trinity" test of the weapon on July 16, and had the opportunity to witness the mission to Nagasaki as an observer.

He wrote about the experience for the Times in a Page 1 story published September 9, 1945. An editor's note atop the piece referred to Laurence as a "special consultant" to the War Department.

I watched the assembly of this man-made meteor during the past two days, and was among the small group of scientists and Army and Navy representatives privileged to be present at the ritual of its loading in the "Superfort" last night, against a background of threatening black skies torn open at intervals by great lightning flashes.

It is a thing of beauty to behold, this "gadget." In its design went millions of man-hours of what is without doubt the most concentrated intellectual effort in history. Never before had so much brainpower been focused on a single problem.

Capt. Frederick C. Bock was at the controls of Laurence's plane. His usual ship, Bockscar, was at the front of the line, with Maj. Charles W. Sweeney tasked with delivering the payload known as "Fat Man" to Nagasaki. (Laurence incorrectly identifies the lead bomber as The Great Artiste throughout his story, as that was Sweeney's usual plane and the bombers flew without nose art.)

Laurence moved throughout the bomber during the flight, chatting up various members of the crew. Anticipation builds as the B-29s near the target area, arriving shortly after noon on August 9.

We heard the prearranged signal on our radio, put on our arc-welder's glasses and watched tensely the maneuverings of the strike ship about half a mile in front of us. "There she goes!" someone said.

Out of the belly of The Great Artiste what looked like a black object went downward. Captain Bock swung around to get out of range; but even though we were turning away in the opposite direction, and despite the fact that it was broad daylight in our cabin, all of us became aware of a giant flash that broke through the dark barrier of our arc-welder's lenses and flooded our cabin with intense light.

We removed our glasses after the first flash, but the light still lingered on, a bluish-green light that illuminated the entire sky all around. A tremendous blast wave struck our ship and made it tremble from nose to tail. This was followed by four more blasts in rapid succession, each resounding like the boom of cannon fire hitting our plane from all directions.

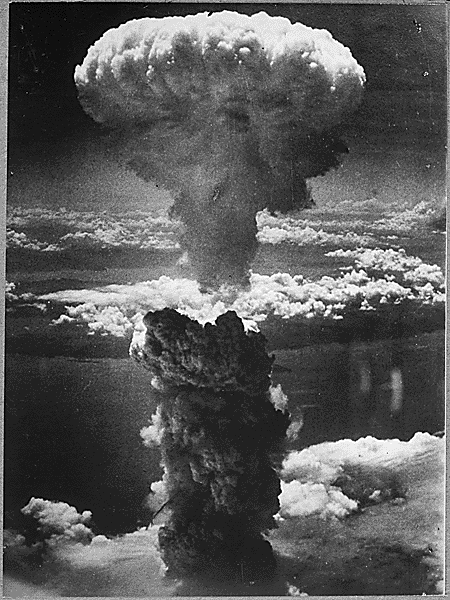

Observers in the tail of our ship saw a giant ball of fire rise as though from the bowels of the earth, belching forth enormous white smoke rings. Next they saw a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000 feet high, shooting skyward with enormous speed.

The Great Artiste turned back toward the explosion about 45 seconds after the blast, presenting Laurence with an otherworldly scene.

It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born right before our incredulous eyes.

At one stage of its evolution, covering millions of years in terms of seconds, the entity assumed the form of a giant square totem pole, with its base about three miles long, tapering off to about a mile at the top. Its bottom was brown, its center was amber, its top white. But it was a living totem pole, carved with many grotesque masks grimacing at the earth.

Then, just when it appeared as though the thing has settled down into a state of permanence, there came shooting out of the top a giant mushroom that increased the height of the pillar to a total of 45,000 feet. The mushroom top was even more alive than the pillar, seething and boiling in a white fury of creamy foam, sizzling upward and then descending earthward, a thousand Old Faithful geysers rolled into one.

Laurence closes the piece with one last look at the seemingly permanently altered sky, the cloud now evolved from a mushroom to "a flowerlike form," still visible to the observers from a distance of 200 miles.

The same day that piece ran in the Times, exactly one month after the detonation at Nagasaki, Laurence and other journalists got a tour of the Trinity test site, designed explicitly to counteract stories of the devastation that had emerged from Japan.

Laurence's front-page story from September 12 is based on a staggering premise. Its headline reads "U.S. ATOM BOMB SITE BELIES TOKYO TALES" and it opens with these paragraphs:

This historic ground in New Mexico, scene of the first atomic explosion on earth and cradle of a new era in civilization, gave the most effective answer today to Japanese propaganda that radiations were responsible for deaths even after the day of the explosion, Aug. 6, and that persons entering Hiroshima had contracted mysterious maladies due to persistent radio activity.

To give the lie to these claims, the Army opened the closely guarded gates of this area for the first time to a group of newspapermen and photographers to witness for themselves the readings on radiation meters carried by a group of radiologists, and to listen to the expert testimony of several of the leading scientists who had been intimately connected with the atomic bomb project.

The story goes on to describe at length the blast damage around the Trinity site and notes that Geiger counters measured only a "minute quantity" of radiation around most of the site. Of course, this was nearly two months after the explosion.

It also includes repeated assertions from scientists and military officials that radiation was responsible for little, if any, of the casualties from the explosions. Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, who led the project, goes on the record on this point before getting to the overarching justification for deployment of the weapons, and Laurence chimes in his agreement afterward.

"The Japanese claim," General Groves added, "that people died from radiations. If this is true, the number was very small.

"However, any deaths from gamma rays were due to those emitted during the explosion, not to the radiations present afterward. In the area where people could be killed by radiation they were killed by other causes, particularly blast.

"While many people were killed, many lives were saved, particularly American lives. It ended the war sooner. It was the final punch that knocked them out. Otherwise they might have kept on fighting for a longer period."

The Japanese are still continuing their propaganda aimed at creating the impression that we won the war unfairly, and thus attempting to create sympathy for themselves and milder terms, an examination of their present statements reveals.

Here we must step back and remember atomic weapons were an entirely new phenomenon, and little was known about their effects. But the air of certainty in Laurence's tone is striking, particularly given U.S. officials obviously would have just as much at stake in terms of propaganda as the Japanese would -- if not more so.

That story, incidentally, carried a "Special to The New York Times" byline, indicating Laurence was not a staffer. But two weeks later, on September 26, his regular byline was back, his War Department work apparently done. That piece was the first of nine Laurence stories on the atomic project published over the next three weeks.

That series, plus the two previous articles already cited, won Laurence the Pulitzer Prize for reporting in 1946. It was his second such award, as he shared the reporting prize with four other journalists in 1937.

When he wasn't veering into counter-propaganda efforts, Laurence's stories were unabashed celebrations of the science behind the atomic bomb project, lauding the pure engineering that had ushered in an entirely new era. But it wasn't until The New Yorker published John Hersey's seminal piece "Hiroshima" in August 1946 that the human cost of atomic weapons truly became clear. Hersey's reporting sketched out the details of radiation sickness in harrowing terms, detailing the bomb's lingering effects on those who survived the blast.

In August 1946, Laurence published Dawn Over Zero, a book about the atomic tests, and he would produce three more books about nuclear weapons in the 1950s. He continued to write occasionally for the Times while also serving as its science editor before retiring from the paper on January 1, 1964.

Laurence died March 19, 1977 at age 89.