Killed by friendly fire: Lesley J. McNair and Bede Irvin

As the slog through the Normandy bocage wore on six weeks after D-Day, Allied commanders kept pressing for a way to break out, wary of falling into a World War I-style stalemate. With Caen and Saint-Lô finally in hand by mid-July, Operation Cobra was their latest attempt to shake free of hedgerow fighting and get on with truly expanding their foothold in Northwest Europe.

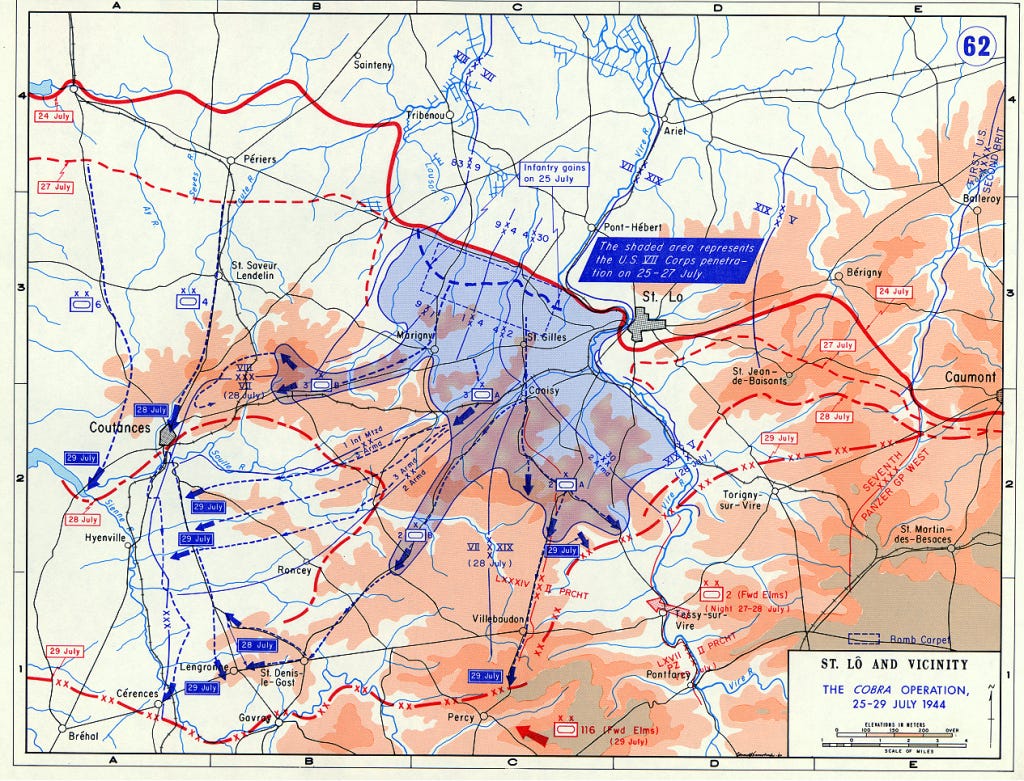

In an effort to give the attack by the U.S. VII Corps the best possible chance of success, planners ordered heavy aerial bombardment on German positions south of the Périers-Saint-Lô road (the dashed rectangle in the map below) to soften up the defenses. The plan included fighter-bombers accustomed to close air support but also heavy bombers that were not used to such precision work.

The decision to include higher-altitude bombers from the Eighth Air Force for tactical support would prove costly, as bombs that fell short of the target area ended up killing more than 100 Americans, including a key member of the U.S. Army braintrust and an Associated Press photographer.

Days before Operation Cobra launched on July 25, George Bede Irvin, known to all by his middle name, joined several AP colleagues in the field in meeting with London bureau chief Robert Bunnelle and AP executive Lloyd Stratton, who were on a tour of the battle front, in St. Andre.

The group, which also included star AP correspondents Hal Boyle and Don Whitehead, posed for a group photo to mark the occasion. At some point during the visit, Irvin -- who had flown over the invasion beaches on D-Day and been in France since June 8 -- told Bunnelle and Stratton that his only complaint was not seeing enough action.

Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair had a better claim to that complaint. The 61-year-old was one of the most respected men in the Army, a 1904 West Point graduate who was considered one of the service's brightest minds and played a significant role in shaping doctrine and training methods. What he didn't have in World War II, however, was a field command.

That changed, sort of, when he was tabbed as the "successor" to Gen. George S. Patton as commander of the First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) -- the fictitious element that played a key role in the deception campaign around Operation Overlord. Though D-Day was more than six weeks in the past, the Allies were trying to maintain the illusion that FUSAG was an entity worthy of German concern, so they kept the story alive.

McNair, who had been wounded in Tunisia during a visit to observe the battlefield in 1943, was slated to do the same near Saint-Lô as Operation Cobra jumped off. He was with the 30th Infantry Division's 120th Infantry Regiment as an observer, northwest of Saint-Lô, when the aerial bombardment began.

The 4th Infantry Division held the sector adjacent to the 30th, and Scripps Howard correspondent Ernie Pyle was with that battle-hardened group. Weeks later, he would write of what occurred on July 25, leaving out dates and locations.

A column that ran in numerous newspapers on August 10 began by noting, "It is possible to become so enthralled by some of the spectacles of war that you are momentarily captivated away from your own danger." That's exactly what happened to Pyle and a small group of soldiers watching the bombardment that day.

As we watched, there crept into our consciousness a realization that windrows of exploding bombs were easing back toward us, flight by flight, instead of gradually forward, as the plan called for. Then we were horrified by the suspicion that those machines, high in the sky and completely detached from us, were aiming their bombs at the smokeline on the ground -- and a gentle breeze was drifting the smokeline back over us!

An indescribable kind of panic comes over you at such times. We stood tensed in muscle and frozen in intellect, watching each flight approach and pass over us, feeling trapped and completely helpless. And then all of an instant the universe became filled with a gigantic rattling as of huge, dry seeds in a mammoth dry gourd. I doubt that any of us had ever heard that sound before, but instinct told us what it was. It was bombs by the hundreds hurtling down through the air above us.

Pyle described diving to the ground and squirming under a wagon in a desperate search for cover.

There is no description of the sound and fury of those bombs except to say it was chaos, and a waiting for darkness. The feeling of the blast was sensational. the air struck you in hundreds of continuous flutters. You ears drummed and rang. You could feel quick little waves of concussions on your chest and in your eyes.

Pyle wrote of worrying about Newsweek correspondent Ken Crawford, who was also embedded with the 4th, and what might have become of him. It wasn't until three days later, back at the press camp, that Pyle discovered Crawford was OK -- but Bede Irvin had been killed in the bombing.

The initial AP report of Irvin's death made it into the evening Des Moines Tribune in Irvin's hometown the same day. Details about how he died were not available for that edition, but the sad truth emerged within hours, time enough to make July 26 morning editions back home.

Wes Gallagher wrote the main AP story, which began this way: "Bede Irvin, Associated Press photographer, who went to see the war close up, died Tuesday with a camera in his hand." The second paragraph of Gallagher's dispatch reported that Irvin had died "when a bomb from a B-26 Marauder fell short of its objective in the middle of a field where Irvin had been working."

The story leaned on Lee McCardell of the Baltimore Sun, who was with Irvin at the front, for most of its details. McCardell reported Irvin had already shot photos of the bombardment farther up and was having lunch in his jeep near Pont-Hébert, four miles from Saint-Lô, when the barrage started drifting back.

"Someone shouted, 'Watch out, bombs from the Marauders are falling short,' and everyone started running," McCardell said. "Irvin had been sitting in a jeep and apparently he hesitated a split second to pick up his camera before diving for a nearby ditch. He was caught in mid-air by a bomb fragment and killed instantly."

Irvin was found by McCardell crumpled in a ditch with one camera around his neck and the other lying near an outstretched hand.

Irvin had been assigned to the Ninth Air Force at the time of his death, and the unit's commander, Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, issued a statement on July 26 acknowledging that the photographer had been "killed by the explosion of a bomb from one of our own bombardment aircraft" before going on to praise Irvin:

"He was an unarmed observer who, heedless of personal danger, flew with us, lived with us and worked with us that through the medium of his profession he might bring home to all of us the truths of war.

"During the period of his assignment with the Ninth Air Force, I came to know Mr. Irvin well. He flew frequently as a photographic observer with our medium bombers and performed exceptionally meritorious service in the pictorial coverage of personnel and activities of the entire air force.

"I feel a deep sense of personal loss at his passing, which should be regarded by one and all as the loss of a highly trained professional soldier who died in the service of his country."

On July 28, Irvin was buried at the military cemetery at La Cambe, west of Omaha Beach, with numerous correspondents and photographers in attendance. Among them was Gordon Gammack of his hometown Des Moines Register, who wrote: "The service was simple and much as I think Bede would have wanted. During it the fighter-bombers he had photographed so many times roared overhead on their way to smash German positions."

Lee McCardell, who was with Irvin at the end, offered up this remembrance:

Like other correspondents here, I have tried for two days to write a tribute to him, one of the finest men any of us ever knew. But words are inarticulate. We all loved him too deeply and admired him too much for what he was -- an honest, gentle, genuine man, whose soft voice and sweet ingratiating smile we will never forget. Bede was even dearer to those ho had known him better and loved him longer.

And so many other good men, and true, die here, equally loved and far from those who love them, that our brief in his case is a poor and tiny thing indeed in a world awash with others' tears. We can only record it humbly from the bottom of our hearts.

While the true cause of Irvin's death was public hours later, the same could not be said of McNair. On July 27, the War Department in Washington released a statement that raised more questions than it answered: "The War Department has been notified of the death of Lt. Gen Lesley J. McNair. Gen. McNair was killed by enemy fire while observing the action of our front line units in the recent offensive."

McNair was sufficiently well-known that the two-sentence statement made big news. The Washington Evening Star ran a lengthy story on him in its July 27 editions, and the story was on Page 1 of The New York Times the following day, noting that Gen. George C. Marshall reportedly had once referred to McNair as "the brains of the Army."

Both stories made mention of McNair giving up command of Army Ground Forces earlier in July to take up an "undisclosed" assignment overseas. That imaginary billet as FUSAG's leader led to the delay in revealing to the public how McNair had actually died.

The truth didn't emerge until August 2, when the War Department announced that McNair had in fact been killed by an American bomb. The somewhat convoluted official explanation acknowledged that Lt. Gen. Brereton had already said friendly fire was responsible for some Allied casualties on July 25:

"A full explanation developed the fact that General McNair died as a result of the explosion of one of our own bombs which fell short in the intensive bombardment of enemy lines just preparatory to the present large-scale American breakthrough in Normandy.

"Details of this tremendous air support were given recently in England by Lt. Gen. Brereton, AAF, together with the fact that some of the bombs unfortunately fell among our own forward troops, causing a number of casualties. General McNair, who was observing the action with a front-line infantry unit, was one of those casualties."

In the delay before release of the actual cause of death -- not to mention the straight reporting of said explanation on the front page of The New York Times and numerous other papers -- we see the effects of wartime censorship. In that same August 3 edition, Times military analyst Hanson Baldwin took a shot at the initial story, writing that "the issuance of this first announcement was a grave mistake, for reports that General McNair's death was caused by our own bombs were already circulating in London at that time."

Baldwin then went on to describe his own experience near Pont-Hébert on July 24, the day Operation Cobra had been slated to start before poor weather forced a last-minute, one-dayAn postponement. Some bombers didn't get the message, however, and dropped payloads that missed the target area. That mistake killed at least 25 U.S. troops and wounded more than 100 while foreshadowing the deadly debacle still to come the following day.

An August 6 Washington Post editorial scolded the War Department for "a form of disingenuousness with which the public has become increasingly familiar" in releasing its initial report that McNair had been killed by enemy fire, but news outlets had little recourse. If they wanted to be in-theater covering the war, they had little choice but to abide by the rules put in place by military officials.

McNair and Irvin now lie at rest in the Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer.

A few months after his death, Irvin's widow Kathryn wrote to AP photographer Danny Grossi thanking him for providing him some details about how her husband had died. In a column filed from Germany on October 11, 1944, AP columnist Hal Boyle quoted extensively from the letter:

"I don't know if you are married, Danny, but there are so many hopes and plans between a husband and wife. Plans that won't for Bede and myself ever come true. Nothing we ever dreamed of together can ever come true now. Little sounds of shattering hopes and dreams are big noises now -- nothing to hope for -- and no understanding. ...

"Not seeing Bede around the house isn't an unusual thing for me -- it has been a long time since we were together in our own apartment. For you boys in London it is different. You have seen Bede more recently than I. You have eaten with him, talked with him, been around him -- and now that he is gone it is hard in another way for all of you, too. ... I know how heavy your hearts will be ... and how carefully dry your eyes will be as you carefully try to avoid mention of Bede's name.

"I, too, have things to face. There will be no more dinners for us together, no more future to dream of and plan on together. But most of all there will be no more Bede. No more Bede to ever meet again. No Bede ever coming home again."