Operation Dragoon: 'The decisive blow for France'

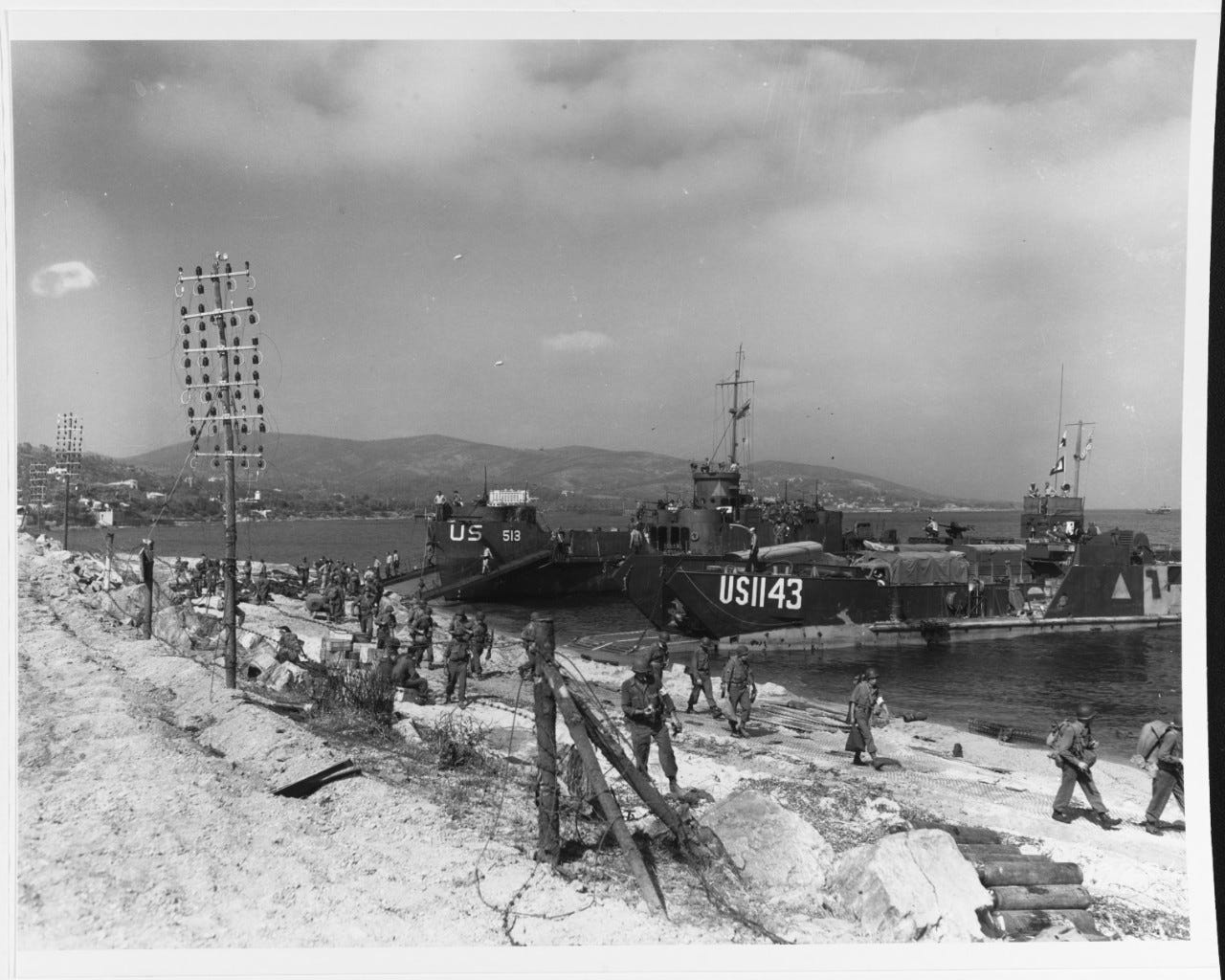

Many of the Allied troops preparing to storm the beaches of southern France the morning of Aug. 15, 1944 were expecting the worst, with visions of a chaotic landing like Omaha Beach and an ensuing stalemate like Anzio clouding their thoughts.

Much to their relief, they got neither as they succeeded in putting yet another liberation force ashore on the continent and keeping them there.

Herbert L. Matthews summed up the mood on the ground on the front page of the next day’s New York Times:

An American Army numbering many thousands is well into southern France this afternoon and going fast. It has struck virtually without opposition and with amazingly small casualties. The Germans were caught completely by surprise. What few were waiting for us have been scattered or captured.

Men, tanks, artillery and material of all kinds have been pouring into three separate beaches since H-hour at 8 A.M. today. By now we have built up such strength that it seems almost certain that we have come not only to stay but also to push on.

This ought to be the decisive blow for France, and everybody is astounded that it went off so easily.

Many of the troops involved in Operation Dragoon were veterans of the Mediterranean theater who had been in Sicily and Italy. The same went for most of the correspondents, who had lamented missing out on the big show in Normandy two months earlier but now had France datelines of their own.

Chicago Tribune correspondent Seymour Korman’s dateline on Aug. 16 read WITH U.S. GROUND FORCES NEAR STE. MAXIME, where he noted it appeared Allied forces had been in place for weeks.

But he and the troops he accompanied remained wary after their experiences attempting to expand beachheads in Italy.

“This has been almost too easy,” said an infantry captain who has been in previous American amphibious operations in this theater. “But none of us are going to make the mistake some did at Anzio, when they thought the war was over because the initial landings were unopposed.”

That feeling of caution against writing off German defensive stands and counterthrusts is prevalent among our veteran soldiers, who remember Anzio and the south coast of Sicily and how much power the enemy hurled at us there after our arrival had been comparatively unmolested.

The quiet reception that greeted the arriving troops was not due to any great focus on maintaining surprise. Unlike the Normandy invasion, where secrecy was paramount, word of this operation had been out there in the wind for some time.

Eight days before the landings, Charles de Gaulle broadcast to the French people from Algiers, promising that “soon, very soon, a powerful French army with the most modern equipment will be deployed on the inter-allied front in France.”

An editorial in the Aug. 9 Boston Globe read between the lines: “The French Mediterranean coast is obviously a danger spot for Hitler. With scores of French divisions ready and waiting in Corsica, Sardinia and North Africa, the hour approaches for action. Does de Gaulle’s powerful summons presage the opening of a new front in France?”

An Associated Press story by James M. Long filed from Eisenhower’s headquarters on Aug. 13 noted a third consecutive day of Allied bombing on the southern coast of France and inferred that might be a harbinger of something bigger.

The following day, German radio said Allied convoys were heading through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean and speculated that landings were imminent, with southern France, the Greek islands and a new front in Italy mentioned as possible locations.

So it was that once the landings went off on the 15th, the AP moved a brief story calling the invasion “perhaps the worst-kept secret of the war.”

Thousands of Frenchmen and Americans knew it was coming. Correspondents in Normandy and Brittany were constantly asked about it both by Frenchmen and GIs.

The question was among the first asked by Frenchmen in towns which had been captured. The French underground probably was told of the impending invasion and they told everyone else.

In Algiers, New York Times correspondent Harold Callender said “the imminence of the blow had been common knowledge for several weeks, and even the date had been more or less accurately discussed in the cafes.”

Aboard a U.S. light cruiser in the invasion fleet, Price Day of the Baltimore Sun was just as perplexed about the Germans’ lack of anticipation, “though from our bombings and their own reconnaissance and intelligence they must have known an attack on southern France was imminent.”

Not that the invaders were complaining. As the sun slowly rose, illuminating the Allied fleet off the French coast, Day wrote a passage eerily similar to what, 18 years later, would become one of the most memorable scenes in the screen adaptation of Cornelius Ryan’s The Longest Day, in which Maj. Werner Pluskat watches the invasion armada appear seemingly out of thin air from his seaside bunker:

In three quarters of an hour the dark had begun to lift and long black blobs of every type of ship appeared slowly in a widening arc on all sides.

“I’d give $100 to see the fact of the first guy that sees this,” said a signalman.

I thought for a moment that I could see the shoreline ahead but it turned out to be more vessels. It was as if the skyline of a city circled the entire horizon with a great ship-filled lake in the middle.

After the first day, Allied operations in southern France didn’t generate many banner headlines in North America and Britain, particularly as the spearhead from Normandy closed in on Paris over the coming days. But to the French themselves, the operation at the very least had great symbolic importance.

While U.S. troops made up the first wave on Aug. 15, French forces followed behind. AP correspondent Joseph Dynan went ashore on the Riviera with those troops, many of whom had fought in the opening months of the war before their country fell to the onrushing Nazis in 1940. Some had been training in North Africa for more than a year before Dragoon, yearning for a chance to rejoin the fight.

One French lieutenant told Dynan: “We are glad of the Allied assaults, but we want the liberation to be our own effort at least in part. We want to even our scores with the Germans for the defeat of 1940.”

Dynan described the scene as they moved inland:

A group of 60 German prisoners goosestepped into a stockade at the other side of the road. There were some civilians among them.

“Frenchmen helping the Germans,” at GI explained.

French officers stared in amazement and disgust.

The first French civilian the French troops encountered failed to recognize them as such in the gathering gloom. In shorts, he calmly rode a bicycle past without turning his head.

But the next was enthusiastic — in fact he was drunk. In a torn, dirty shirt he stood in front of the wreckage of a beachside restaurant waving a bottle of wine, ten tried to embrace and kiss French soldiers.

The following day, Dynan explored St. Tropez, where he noted numerous houses had been destroyed.

“We gladly lose our homes to get rid of the Boche,” one woman told him.