Liberation Day: When Paris went mad

In view of the number of correspondents who claimed, over the years, to have been the first to return to Paris after the German occupation, I should have been more careful to note my place in the column entering the city.

So wrote Andy Rooney, later a CBS curmudgeon but then a 25-year-old correspondent for Stars and Stripes, in his memoir My War. Rooney was without question among the first groups of journalists to enter the liberated city, accompanying French Gen. Philippe Leclerc's armored column on the morning of August 25, 1944.

But the dateline competition he referred to in his book as a "silly game" was all too real for many reporters, particularly those working for wire services. As he went on to note, some of his peers had been known to edge their jeep just across a coveted boundary, then hightail it back to the nearest press camp to file their story topped by a coveted geographic signifier.

This happened throughout the war, across multiple theaters, but no dateline was more coveted than the one finally attained on that long-awaited day.

"PARIS, Aug. 25" trumpeted James McGlincy's United Press dispatch beamed to the world that day. Though it's unclear who among the correspondents actually made it in first, McGlincy is generally acknowledged to have filed the first report from inside the city.

His dispatch went out via a broadcast to New York from a French radio station, circumventing official censorship channels. That earned McGlincy and the five other correspondents who followed him to the microphone suspensions from SHAEF, but he didn't care. He had reported the news of one of the most anticipated moments of the war:

A new French revolution raged in the streets of Paris today.

French and American forces stabbed into Paris preparing to battle the heavy German forces.

They fought from barricades and houses. They fought with rifles and machine guns. Sometimes they fought with their hands.

And the citizens of Paris fought beside the soldiers. They fought like their forefathers did under Danton and Robespierre.

"Vive la France" is the cry, says the morning L'Humanite. That is the war cry of the Parisians armed to the teeth to repulse the Hitler horde.

Another reporter embedded with French troops determined that if he was not necessarily the first correspondent to reach the city, he probably was the second Canadian, after the army public relations photographer traveling with him.

Matthew Halton's joy seeps through a nearly nine-minute report recorded on the 26th. Though his tone is typically calm, his delivery even, you can feel the elation bubbling beneath his polished delivery.

"This is Matthew Halton of the CBC speaking from Paris," he began, before repeating, as if to convince himself, "Speaking from Paris. I am telling you today about the liberation of Paris, about our entry into the town yesterday, and I don't know how to do it. Though there was still fighting in the streets, Paris went absolutely mad. Paris and ourselves were in a delirium of happiness yesterday, and all last night, and today. Yesterday was the most glorious and splendid thing I've ever seen."

That notion was the common thread through most correspondents' initial dispatches from the liberated city. This was especially true of those who had known the city before the German occupation, like Halton. He mentions in his report that it is five years to the day of his last visit to Paris in 1939, about a week before Germany invaded Poland to spark a worldwide catastrophe.

A.J. Liebling of The New Yorker had first come to Paris as a 21-year-old to study at the Sorbonne and returned as a correspondent when war broke out, fleeing the city along with the French government on June 10, 1940 as Nazi troops rolled toward the capital. His first "Letter From Paris" to The New Yorker after liberation began with a classic line:

For the first time in my life and probably the last, I have lived for a week in a great city where everybody is happy.

Moreover, since this city is Paris, everybody makes this euphoria manifest. To drive along the boulevards in a jeep is like walking into some as yet unmade René Clair film, with hundreds of bicyclists coming toward you in a stream that divides before the jeep just when you feel sure collision is imminent.

Among the bicyclists there are pretty girls, their hair dressed high on their heads in what seems to be the current mode here. These girls show legs of a length and slimness and firmness and brownness never associated with French womanhood.

Food restrictions and the amount of bicycling that is necessary in getting around in a big city without any other means of transportation have endowed these girls with the best figures in the world, which they will doubtless be glad to trade in for three square meals, plentiful supplies of chocolate, and a seat in the family Citroën as soon as the situation becomes more normal.

For correspondents accustomed to living in the field with the troops, some of whom had been chronicling bloodshed from North Africa to Sicily to Italy and across France, this day would stand out as a desperately needed respite.

Count the battle-weary Ernie Pyle among that group:

I had thought that for me there could never again be any elation in war. But I had reckoned without the liberation of Paris -- I had reckoned without remembering that I might be a part of this richly historic day.

We are in Paris -- on the first day -- one of the great days of all time. This is being written, as other correspondents are writing their pieces, under an emotional tension, a pent-up semi-delirium.

Much of Pyle's initial column from that first day is a rehashing of scenes shared in every correspondent's copy -- from the interminable wait at Rambouillet before reaching the city to being mobbed and kissed by every French man, woman and child lining the streets upon entry.

That was unusual for Pyle, whose hallmark was finding that angle no one else noticed -- or at least describing the familiar in a unique way. Apparently he had the same sense of that first effort, as his follow-up dispatch includes a couple of paragraphs essentially apologizing for not being able to do the moment justice.

Actually the thing has floored most of us. I know that I have felt totally incapable of reporting it to you. It was so big I felt inadequate to touch it. I didn't know where to start or what to say. The words you put down about it sound feeble to the point of asininity.

I'm not alone in this feeling, for I've heard a dozen other correspondents say the same thing. A good many of us feel we have failed in properly presenting the loveliest, brightest story of our time. It could be that this is because we have been unused, for so long, to anything bright.

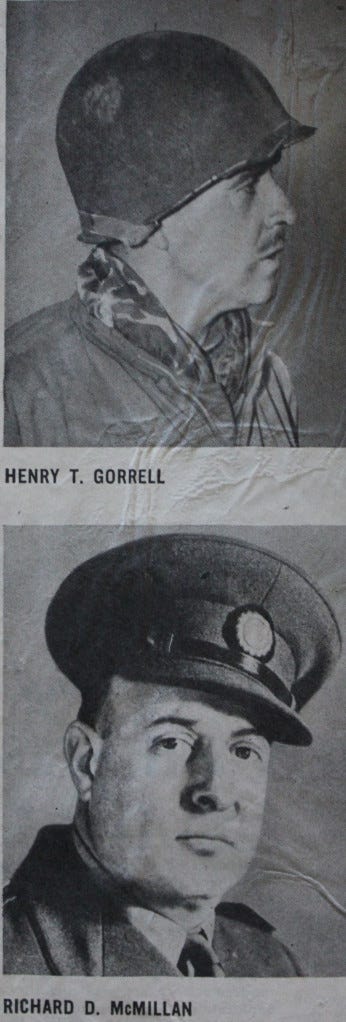

Pyle entered Paris in a jeep with United Press correspondents Henry T. Gorrell and Richard D. McMillan, who had a specific mission in mind the day after the liberation.

Heading toward the Opera, they weaved past German tanks destroyed by Molotov cocktails fashioned from champagne bottles and stopped at 2 Rue des Italiens -- UP's former Paris bureau office. In Gorrell's telling, the building caretaker's wife recognized McMillan due to his years stationed at the bureau and shouted, "Ah, you have returned at last! Vive L'Amerique!"

The woman tracked down Emilio Herrero, a Spaniard who had worked for UP before the occupation and had been entrusted with the keys by bureau chief Ralph Heinzen when he closed up shop in June 1940. Herrero had taken it upon himself to remove several typewriters from the building, along with critical office records, and hide them at his home.

So it was that although the Germans had taken the "fine mahogany desks" from the office, Gorrell was able to sit down in the reopened UP bureau and compose his story on one of the typewriters hidden away by Herrero.

Two days later, New York Times correspondents Harold Denny, Frederick Graham and Gene Currivan enjoyed a similar reunion with locals who had worked at the Times bureau at 37 Rue de Caumartin through December 1941. Wrote Denny:

Together we hunted up what we could find of our French staff. Of all the reunions that we have had with French friends since our entrance Friday, none has been so touching as those today with these people who worked together with us in this office in the days between the two wars. To them it was the restoration of their bureau besides being the liberation of their country's capital. They have fared variously.

The Times men found the office had been occupied by French tenants, who agreed to let the correspondents set up shop in two rooms in the meantime.

"The New York Times sign has remained over the front of our offices all through the occupation," Denny wrote, "and it is now heaped with American, French and British flags."