Pearl Harbor: A nation thrust into war

On Saturday, November 29, 1941, Honolulu bureau chief Frank Tremaine filed a story to the United Press wire. It ran in numerous newspapers over the next few days, mostly filling out a random inside page here or there.

The Wisconsin State Journal was among the last newspapers to run Tremaine's story, giving it about 12 column inches on page 9 of its Sunday, December 7, 1941 edition. The first paragraph read:

Peaceful Hawaii -- with big guns booming, warplanes droning overhead and defense works springing up like magic -- is taking on the combined attributes of a war capital and a boom defense town, but the situation is neither as acute no as dangerous as some reports recently circulated on the mainland would indicate.

The third paragraph ended with this sentence:

War planes are so common in the Hawaiian skies that only the visitor of a few days bothers to look up as they roar past.

Chances are, just as some Wisconsinite glanced at page 9 that Sunday, perhaps after arriving home from church in the early afternoon, Frank Tremaine was realizing just how prescient and horribly wrong he had been in his piece filed eight days earlier.

Of course, by that point, he had much more pressing issues at hand.

Tremaine and his small staff called in their initial bulletins on the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor to UP's San Francisco bureau, which rushed them out onto the wire. Time is critical in every breaking news situation, but especially so here -- civilian communications to the mainland were quickly cut off, with the military taking over all circuits.

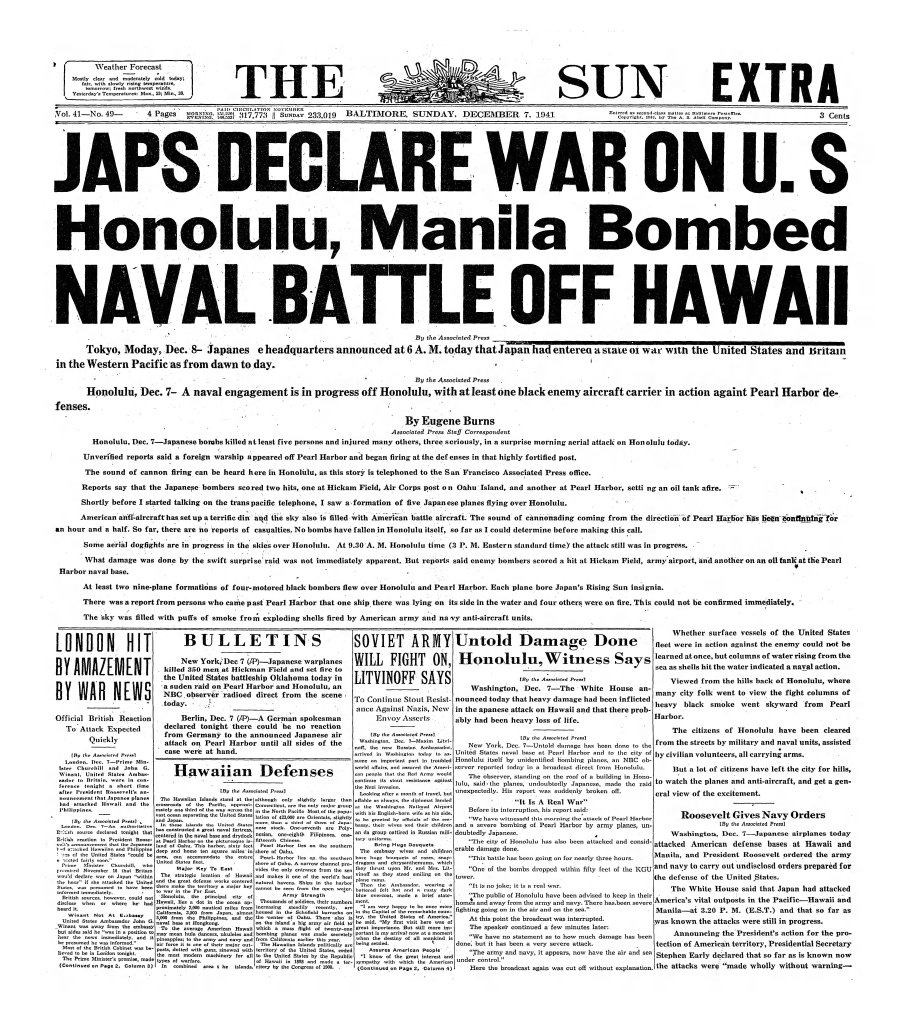

A bylined report from Tremaine printed in the December 8 San Bernadino Daily Sun is heavy on hearsay, with little official information to pass along and no attempt to capture the bigger picture of the event.

Pearl Harbor and Hickam Field, the big army bomber base, apparently were the worst hit. Witnesses reported three fires raging at Pearl Harbor after the first attacks, and said that "at least three ships" were hit at Pearl Harbor, but there was no confirmation of this latter report.

Tremaine later devotes four paragraphs to quotes from an eyewitness to the attack before getting to Honolulu residents' stunned reaction:

The population was caught entirely unawares. At first the detonations were believed to be merely the army and navy engaged in target practice.

The Associated Press' Honolulu bureau chief, Eugene Burns, was eating breakfast at home when he heard the planes fly over.

According to the company's 2007 history Breaking News: How The Associated Press Has Covered War, Peace and Everything Else, Burns immediately called the AP's San Francisco office with a bulletin:

AT LEAST FIVE PLANES, THEIR WINGS BEARING THE INSIGNIA OF THE RISING SUN, FLEW OVER HONOLULU TODAY AND DROPPED BOMBS

There was just one problem. Burns' bulletin never made the wire, and the reasons have been lost to history: "Why it did not remains a mystery; there is no record of what happened to it. Nearly an hour passed before the first word of the attack broke."

That word, like much of the reporting from the first few days after the attack, came from Washington. As the AP's history tells it, D.C.-based editor William Peacock was in the office around 2:20 p.m. ET when the White House called and told him to stand by for a statement from press secretary Stephen Early.

Early then read a one-sentence statement from President Franklin D. Roosevelt announcing the Japanese attack. Peacock instantly typed out a one-line message that would break into the national wire:

FLASH. WASHINGTON--WHITE HOUSE SAYS JAPS ATTACK PEARL HARBOR

Broadcast outlets jumped into action immediately upon getting the AP bulletin and equivalent alerts from the UP and the International News Service.

Old Time Radio has a comprehensive rundown of how the story unfolded on the airwaves, led by NBC's Robert Eisenbach breaking into regular programming -- Sammy Kaye's Sunday Serenade on the Red Network and a Great Plays performance of "The Inspector General" on the Blue Network -- seconds before 2:30 p.m. ET to read the AP's bulletin.

Eisenbach, who had never spoken on the air before, broke the news across a network of 246 affiliates.

Later Sunday, NBC broadcast an eyewitness report from Honolulu affiliate KGU, which you can listen to in full here courtesy of the National Archives:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E7R3XaEbjjg

It was no great surprise that the United States would eventually enter the Second World War, but the shocking preemptive attack provided an instant flashpoint for the press.

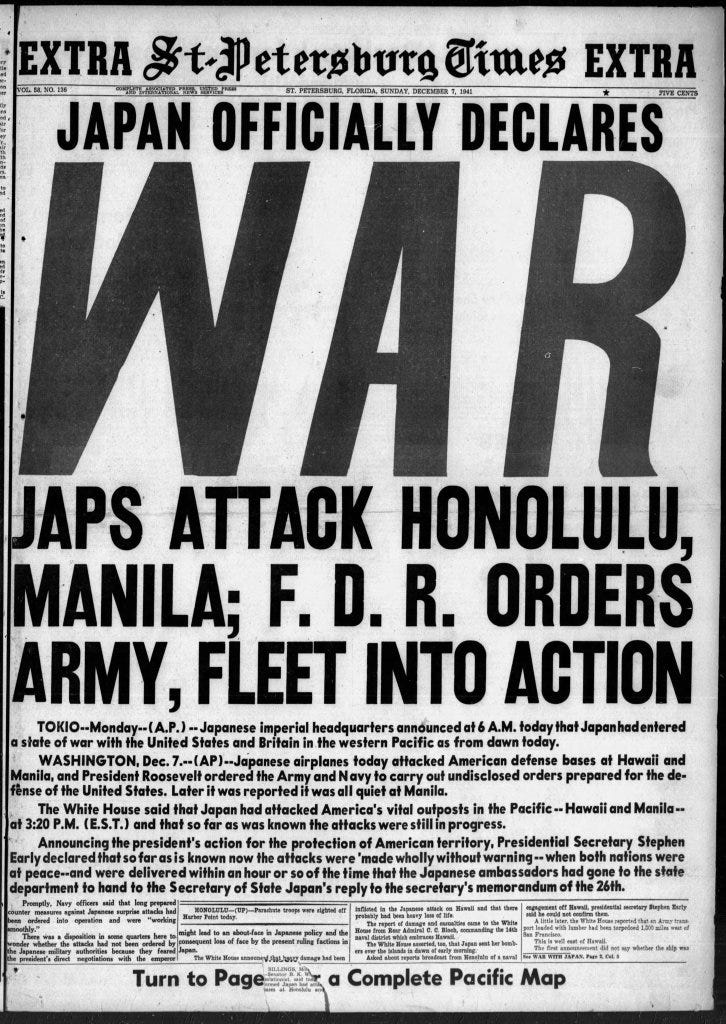

As the initial wire-service bulletins and radio reports sent the news rocketing around the country, dozens of newspapers hastily prepared "extra" editions to hit the streets Sunday afternoon and evening.

In the days after their desperate initial dispatches from the morning of December 7 filled front pages around the world, the wire-service correspondents in Honolulu faced the most infuriating situation imaginable for a journalist: The biggest story in the world had just happened right in their back yard, but the combination of censorship and the communication blackout left them unable to feed news to the outside world for nearly a week.

The next reports from Hawaii-based correspondents that made it to the outside world were datelined December 12, and appeared in some evening newspapers that day and others on the 13th. In their first reports after the blackout, both Tremaine and Burns incorporated first-person slices of how they had experienced the attack and its aftermath.

Tremaine told of arriving at Hickam Field within about 90 minutes of the first raid, where witnesses told him as many as 100 Japanese planes had attacked the base.

While I was inspecting Hickam, a lone Japanese plane swooped down and machine-gunned the group of soldiers guiding me about the post. We dived into a storage room and escaped injury, but nearby automobiles were set afire by the bullets.

Burns' dispatches were more florid, with one lead praising the island's defenders after they "rose to magnificent heights of valor in the face of six vicious raids ... The sudden stab has left them fighting mad."

In a separate piece filed on Friday the 12th, the AP's bureau chief laid bare his frustration with being sidelined from the action.

During that period when it was impossible to send news of the attack we jotted down notes as the incidents occurred. 'Big gas tank fired,' one note read. 'Subsequent blaze put out by heroic action.'

Later in the story, Burns mentioned his wife begging the local telegraph office to let her send a message to her family letting them know they were OK. On Tuesday, she was allowed to transmit a two-word note to her father courtesy of the Democrat-Herald in Albany, Oregon: "Everything fine."

That qualified as news back home, as the Democrat-Herald ran a one-paragraph item noting the same on the front page of its December 9 edition.

But one paragraph toward the end of that Burns dispatch that rings as the most poignant. Client newspapers can always choose how much or how little of a wire service story to run, and how to edit the content. The Santa Rosa Press Democrat in California chose to end the piece with this:

Heretofore in Hawaii, everyone most politely has referred to Japanese as "Japanese." I notice now that the word always is "Japs."

Our next post focuses on the local newspapers' response to the attack, which represented far more to the people of Honolulu than just a turning point in a global war. Click here to read it.