Pearl Harbor: When a global story hits home

Honolulu Star-Bulletin editor Riley Allen arrived at his desk by 6:30 a.m. every day, seven days a week. For most of the nearly three decades he had led the paper, those early mornings -- particularly on the weekend -- had offered mostly peace and quiet to churn through a never-ending pile of work.

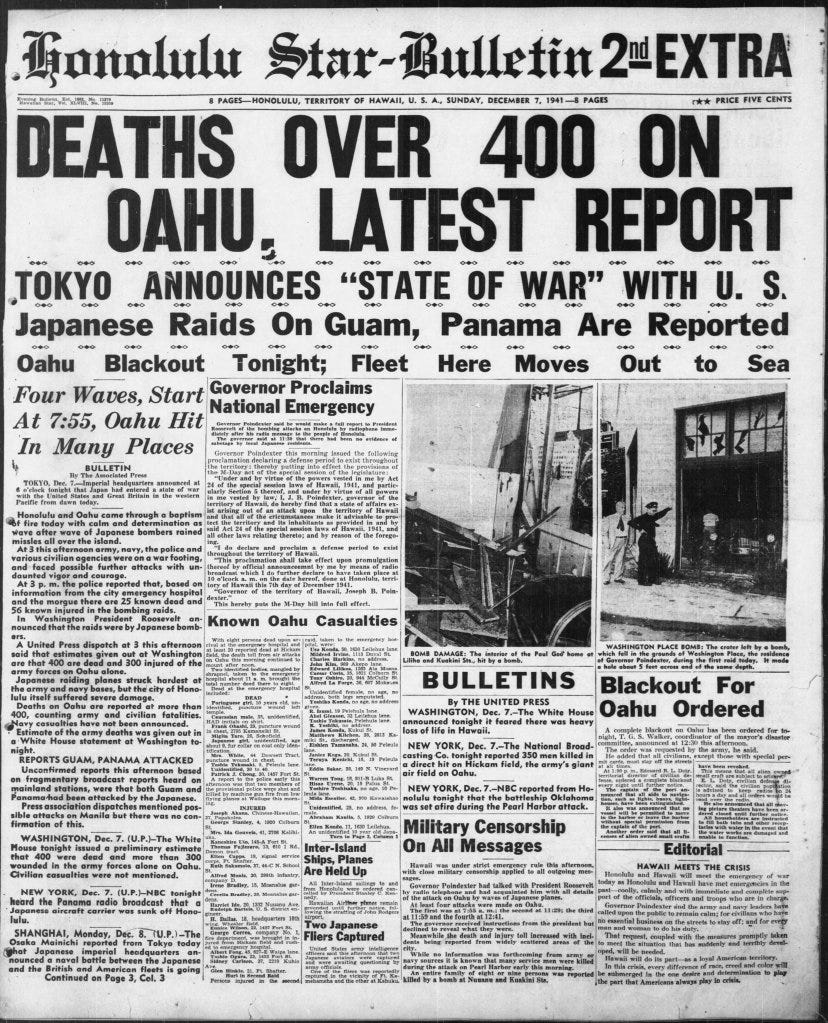

On Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, though, the 57-year-old editor's longtime habit positioned his newspaper for a remarkable performance that would see the Star-Bulletin produce one of the most famous front pages in history.

According to a 1975 profile of the editor in his hometown Seattle Times, the only other people in the Star-Bulletin building when the Japanese attack began around 7:55 that morning were four pressmen doing maintenance on the press.

Robert Clark, the assistant foreman of the advertising composing room, told the Times he had been in around 7 a.m. to catch up on some pre-Christmas advertising but ran out of cigarettes and left the building shortly before 8 to buy some more. He noticed planes flying over the city and like most other locals accustomed to regular activity from Oahu's numerous military bases assumed they were just training exercises -- until an explosion at King St. and Bishop St. made it clear something was wrong.

As I was standing on the corner, Riley Allen came tearing out of the office. 'Get into the building!' he shouted. 'We're getting out an extra! The Japanese are bombing Pearl!'

As Clark began the process of getting the metal melted for typesetting, which could take up to 45 minutes, Allen was at work planning an eight-page extra edition -- the most their presses could handle with some of the rollers down for maintenance.

Mr. Allen wrote out a one-word headline, 'WAR!' and told me to set it in the biggest type we had. Together, we went to the job-printing department where there was bigger type than in the news composing room. I pulled out the various types, and Mr. Allen selected one. It was about five inches high.

That hammer headline would soon take its place in journalism history.

That eight-page edition was the first of three extras the Star-Bulletin would print on December 7. About 250,000 total copies came off the presses that day before it became impractical to print more. Authorities soon ordered most civilians to stay at home, so there wasn't anyone on the streets to buy the extras -- let alone newsboys to hawk them.

(For some context on that circulation number, the population of the entire island of Oahu at the time of the 1940 census was 257,664.)

Even more remarkable for the Star-Bulletin was that it had the entire print market to itself, as the nearby Honolulu Advertiser was caught in the worst possible situation. The Advertiser's press broke Saturday night, leaving it unable to print all day Sunday and into Monday. The situation was dire enough that the Star-Bulletin agreed to print the Advertiser's regular Monday morning edition for its rival.

That product actually made the Star-Bulletin look even better in the eyes of history, as the Advertiser's December 8 front page turned out to be a full-blown journalistic disaster.

The paper ran with a gigantic headline that read "SABOTEURS LAND HERE!" The main story, under the sub-headline "RAIDERS RETURN IN DAWN ATTACK", led with multiple reported events that never actually occurred.

Renewed Japanese bombing attacks on Oahu were reported as Honolulu woke to the sound of antiaircraft fire in a cold, drizzling dawn today. Patriots were warned to be on the watch for parachutists reported in Kalihi. Red antiaircraft bursts shot into the cloudy skies from the direction of Hickam field, which was reported bombed again at about 6 a.m. ...

Warning that a party of saboteurs had been landed on northern Oahu was given early Sunday afternoon by the army. The saboteurs were distinguished by red disks on their shoulders.

While paranoia and confusion were rampant in the hours and days after the Sunday morning attack -- not just in Honolulu but in major cities on the U.S. mainland as well -- there was no further Japanese bombing on December 8, and no evidence that any saboteurs had landed on the island.

The main story did not carry a byline, but a 2001 Star-Bulletin story said then-Advertiser editor George Chaplin later attributed the saboteurs angle to "an unidentified Army source." Chaplin wrote in a 1998 history of the paper that the Army followed up on the report by threatening to shut down the Advertiser if it made any more such wildly inaccurate claims.

While the Advertiser was scrambling for its footing, the Star-Bulletin's staff was churning out copy to fill its extra editions. Summoned via frantic phone calls from Riley Allen as the first wave of attacks unfolded, the newspaper's staff of reporters, photographers and editors expanded coverage with each subsequent extra.

The front page of the second extra featured a completely new design, anchored by two pictures of bomb damage in town. Page one also included a list of known casualties, identifying the dead by name, age and home address when possible. When that level of detail wasn't available, the victims were listed by the information authorities had. Among the dead: "Mrs. White, 44 Dowsett Tract, puncture wound in chest" and "Japanese girl, unidentified, age about 9, fur collar on coat only identification."

Near the bottom of page two of the Star-Bulletin's second extra was a one-sentence item on the army reporting parachute troops "wearing blue uniforms and red shields" landing on Oahu -- the same nugget that led to the Advertiser's front-page whopper the next day.

A new third page of news in the second extra compiled brief items of local interest: "Schools Closed" "Water is O.K." "Blood Donors Are Called In". A fourth page added to the third and final extra included multiple eyewitness accounts of the various attacks.

Aside from a Mr. Ventura Mathias' description of an unidentified battleship at Pearl Harbor being bombed, the focus of nearly all of the Star-Bulletin's coverage on Sunday was the impact of the bombing on the city itself. Yes, there were wire-service accounts of reaction from Washington and abroad, but this was first and foremost a local story to the Star-Bulletin and would remain so going forward.

In its Wednesday, December 10 edition, the Star-Bulletin closed its editorial column with this thought:

The Star-Bulletin believes its greatest service in this critical time is to print the news, so far as that can be done with regard to strategic secrecy in some aspects -- to print it fully, accurately, authoritatively; and by that very dissemination of dependable news to contribute to the order of the community and the successful prosecution of the war in which we are all, civilians as well as the armed services, engaged to the final victory for America and Americans.