PT-109: John F. Kennedy fights to survive in the Solomons

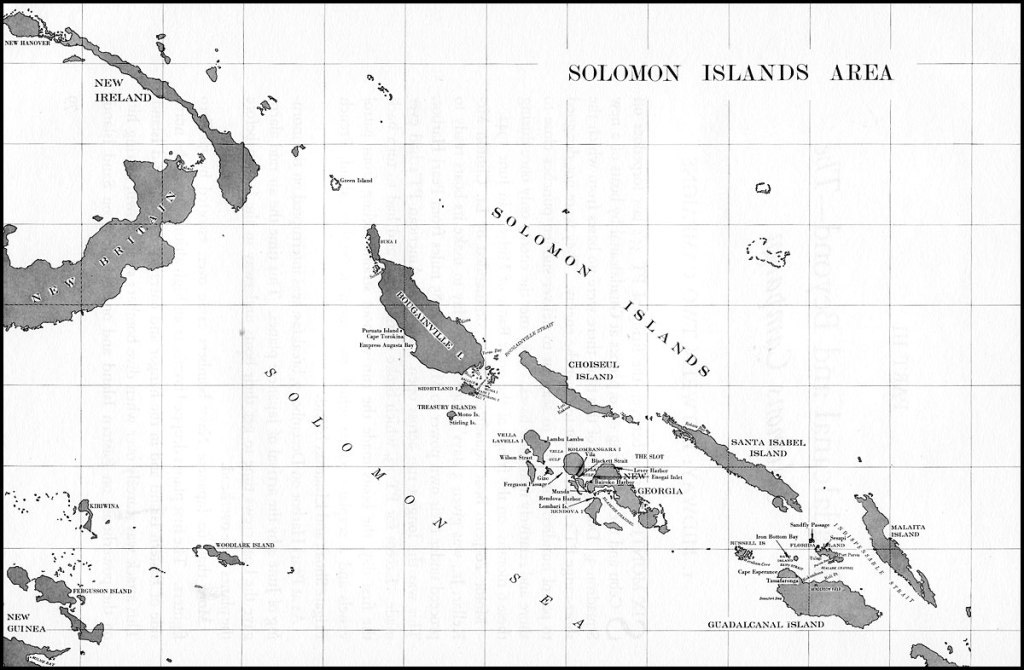

On the evening of August 7, 1943, correspondents Leif Erickson of the Associated Press and Frank Hewlett of the United Press climbed aboard a PT boat at a Navy base at New Georgia in the Solomon Islands to ride along on a rescue mission.

Two days earlier, Lt. (j.g.) John F. Kennedy, skipper of patrol torpedo boat 109, had carved a message into a coconut and entrusted it to a pair of islanders to take back to the base. Its arrival was the first indication that anyone from the vessel had survived a fiery collision with a Japanese destroyer around 2:30 a.m. on August 2.

After sending a canoe carrying food and supplies to the 26-year-old officer and his men the morning of August 7, the Navy sent out the rescue party that evening, and they made contact after midnight. They brought back Kennedy and the other 10 surviving members of his crew, who had avoided Japanese detection for nearly a week.

Erickson and Hewlett were there to tell the story, which first ran in many newspapers August 19 (with August 8 datelines). No outlet played it more prominently than the Boston Globe, where Kennedy not only was a son of the former U.S. ambassador to London but a hometown boy and the grandson of a former mayor.

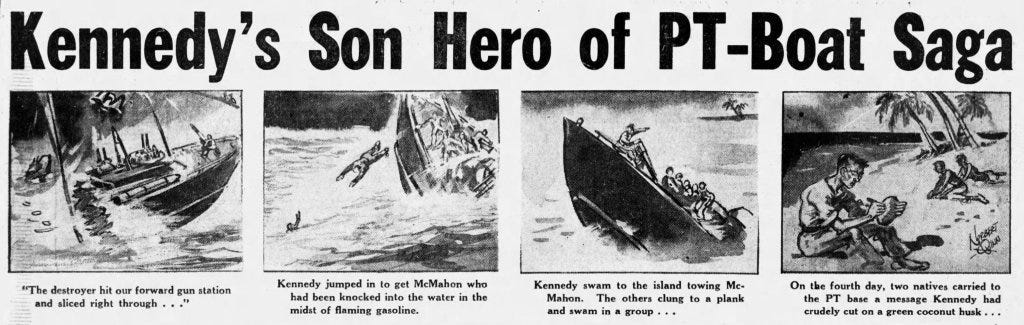

The Globe stripped Erickson's account across the top of its front page, above the masthead, along with four comic book-style illustrations of the story. The rest of Erickson's story ran on Page 6, along with a cut-down version of Hewlett's account, an unbylined story detailing young Kennedy's background and a brief item describing his parents' reaction to the news.

Hewlett's dispatch described the rescue:

Lt. Kennedy rowed out in a native canoe to meet us. He had told us to fire four shots, then he'd answer. We fired four shots. Only three came back through the darkness near the rendezvous point -- then silence for a moment. Then came a louder burst. He had only three cartridges in his .45 caliber pistol. The last shot came from a rusty Jap rifle and the recoil nearly capsized the canoe.

Two trips in the canoe were necessary to bring all the men out to the PT boat. Lt. Kennedy guided us through reefs and coral heads, in constant danger of being seen by enemy planes.

Kennedy and his surviving crew, along with the two native coastwatchers who had facilitated their rescue, climbed aboard Lt. (j.g.) Bill Liebenow's PT-157 for the 40-mile trip back to their base at Rendova Island. Once there, Kennedy regaled the correspondents with the story.

The 109 and two other PT boats had been patrolling Blackett Strait south of Kolombangara early on the morning of August 2 when Kennedy and his crew heard -- but couldn't yet see -- something bearing down on them. From Erickson's AP dispatch:

"At first I thought it was a PT," Kennedy said. "I think it was going at least 40 knots. As soon as I decided it was a destroyer, I turned to make a torpedo run."

But Kennedy, lean and nicknamed "Shafty" by his mates, quickly realized the range was too short for the torpedo to charge and explode.

"The destroyer then turned straight for us," he said. "It all happened so fast there wasn't a chance to do a thing. The destroyer hit our starboard forward gun station and sliced right through. I was in the cockpit. I looked up and saw a red glow and streamlined stacks. Our tanks were ripped open and gas was flaming on the water about 20 yards away."

Two of the 109's crew, Andrew Kirksey and Harold Marney, were killed in the collision -- though they were not named in the initial stories pending notification of their families. Four of the others ended up in the water, and Kennedy and the other two officers aboard, Leonard Thom and Barney Ross, each swam out to retrieve a crewmate, with Kennedy making two trips.

Fighting a strong current, the survivors managed to return to the bow of the 109, which remained afloat thanks to its watertight bulkheads. Kennedy told the reporters they initially seemed headed toward Japanese-held Kolombangara, but the current changed just before daybreak and pushed them in a safer direction.

After about 12 hours in the water, they decided to swim to a nearby island (then called Plum Pudding Island, since renamed Kennedy island), with Kennedy towing badly burned crewman Patrick McMahon to shore. The process took three hours, but they made it ashore and were able to harvest some coconuts for nourishment. They moved to a larger island (Olasana), where they eventually encountered the coastwatchers, but not before Kennedy swam out to Ferguson Passage at night in an attempt to flag down a passing U.S. vessel.

Once back at Rendova, the rest of the crew marveled at McMahon, who had been burned on the face, hands and arms and spent hours afterward in salt water.

"You could see he was suffering such pain that his lips twitched and his hands trembled," Thom told Erickson. "You'd watch him and think if you were in his place you'd probably be yelling, 'Why doesn't somebody do something?' But every time you asked Mac how he was doing he'd wrinkle his face and give you a grin."

McMahon was in no condition to talk to the correspondents with the rest of the crew, but Marine Corps combat correspondent Sgt. Gordon D. Marston tracked him down a couple of months later at a hospital. "I'm alive today because there isn't a more courageous skipper in the South Pacific than Lt. (j.g.) John F. Kennedy," McMahon said.

(McMahon recovered and spent decades working for the U.S. Postal Service after the war. He died in 1990 at age 84.)

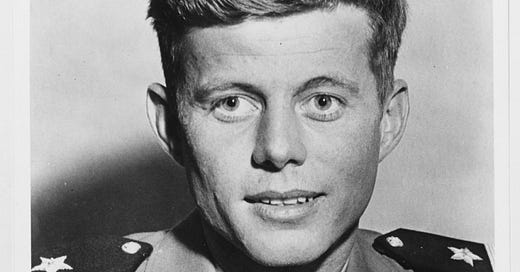

Kennedy's prominent role in helping most of his crew survive the ordeal raised his public profile, and he managed to stay in the news going forward. Anthony La Camera of the Boston Record American wrote a lengthy feature on his background that ran in early September. It was reprinted by several other Hearst papers, including the flagship San Francisco Examiner -- which used a photo of Kennedy's older brother, Joseph Jr., to accompany the story.

After returning to action in the fall as skipper of the PT-59, Kennedy's long-running back problems proved too much to overcome, and Navy doctors took him off the water in mid-November.

He returned to the States early in 1944 and was back home by early February, when the Globe ran a photo of him embracing his grandfather at the former mayor's 81st birthday celebration. "I haven't seen this boy for more than a year, and he's been through hell since that time," said John F. Fitzgerald.

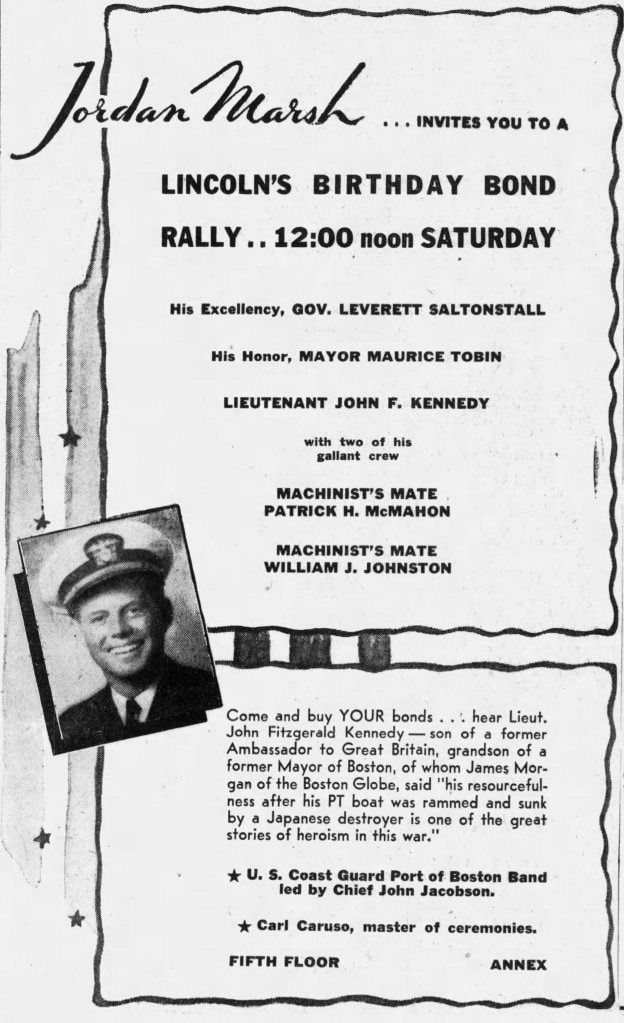

Two days later, Kennedy joined shipmates McMahon and William Johnston (a Dorchester native), mayor Maurice Tobin and governor Leverett Saltonstall at a war bond rally at a Boston store.

The initial PT-109 rescue story received significant coverage across the U.S., both because it was exactly the kind of heroism media outlets and the military craved and because Kennedy's father, the former ambassador, was a well-known public figure.

But young Jack really carved out his own persona once John Hersey did a deep dive into the story for The New Yorker. Hersey's piece, which ran in the June 17, 1944 issue, might as well be a screenplay for the inevitable movie (which finally made it to the big screen in June 1963), with its dramatic reconstruction of the collision and rescue. The account once again leans heavily on Kennedy's men, with the very first paragraph establishing the officer's humility as he suggests the writer go and speak to some of the crew if he really wants to get the full story.

Just under two months later, on August 12, Joe Jr., was killed when a modified bomber packed with 10 tons of high explosives that was supposed to be flown by remote control into a U-boat facility on the German coast exploded prematurely. After the oldest Kennedy brother's tragic death, Jack stepped up to assume the expectations their father had long harbored for Joe: to run for Congress, then the Senate, and ultimately the presidency.

By the spring of 1945, Kennedy was making regular public speaking appearances, usually focused on foreign policy, and writing for Hearst newspapers. His report from London in the wake of Churchill's ouster as Prime Minister in late July was stripped across the top of the Examiner front page, above the masthead.

"England has been hit by some blockbusters in the last five years," he wrote, "but none of them ever shook her like today's election results."

Within a few years, Kennedy would be on the other side of the political reporting equation.