Ralph Barnes: First U.S. war correspondent to fall

Ralph Barnes wasn't even supposed to be involved in the New York Herald Tribune's coverage of the biggest story since the end of the Great War. The 28-year-old was a relative newcomer to the newspaper's Paris bureau and spent most of his time working the desk rather than reporting stories in the field.

On the night of May 21, 1927, the world's attention fixated on Le Bourget airfield, where thousands awaited Charles Lindbergh as he completed the first solo transatlantic flight with a safe landing at 10:21 p.m. local time. The Herald Tribune's bureau chief, Wilbur Forrest, had taken the massive story for himself and left the lesser lights in the operation back at the office. That included Barnes, who had wrapped up his work for the evening and was at a bar with other newsmen in the early hours of May 22 discussing the one loose end yet to be tied in Lindbergh's saga: he still hadn't talked to the press.

Though the aviator had a prearranged deal to tell his tale exclusively to The New York Times, other organizations weren't about to concede without a fight. Everyone had newsmen at Le Bourget, but an exhausted Lindbergh somehow had been whisked away to an undisclosed location and no one could find him. Barnes had spent hours puzzling over it and came to the conclusion that Lindbergh must be at the U.S. embassy, where ambassador Myron T. Herrick's staff already had turned reporters away, denying the flyer was there.

Barnes decided to take one last crack at it and went to the embassy, with other correspondents in tow, around 3 a.m. This time, they talked their way past Herrick, and Lindbergh -- clad in pajamas and a bathrobe -- agreed to meet with them. Afterward, Barnes raced back to the office and struggled to get the story out. Richard Kluger set the scene in his 1986 history of the Herald Tribune, "The Paper":

They shoved the paper into the typewriter for him and poised his fingers over the keys. Nothing. Even as they were about to order him to move over and let somebody else write it while he talked it out, Barnes cleared his brain and began to peck it out. Very slowly. They snatched the copy from his typewriter a paragraph at a time; it was set almost simultaneously in the Paris and New York composing rooms. When Barnes Paused and reached for his notes, they grabbed them away from him: "Just write!"

His 600-word piece was composed almost solely of quotations; the world, after all, was hanging on the airman's words, not some reporter's.

As it turned out, readers wouldn't have known they were Barnes' words even if he had put more of himself into the narrative; the story ran without a byline. Even worse, in his 1934 memoirs, Wilbur Forrest put himself at the embassy, doing the interview, giving no credit to Barnes.

But the younger correspondent had shown his colleagues he could handle a big story, and he was on his way to a career that would take him across Europe over the next decade as the continent deteriorated toward war once again.

Ralph Waldo Barnes was born June 4, 1899 in Salem, Oregon, to Edward and Mabel Barnes. A sister, Ruth, would follow two years later. Their father supported the family as a dry goods merchant.

Young Ralph's name popped up occasionally in the local papers throughout his teenage years, often in conjunction with school arts programs. At one point he even played a reporter in a high school production of "The Man of the Hour."

He stayed close to home for college, enrolling at Willamette University in Salem, but his freshman year was interrupted by a call to military training during the closing months of the Great War. He was discharged from the army in December 1918 in Waco, Texas, and headed back home to resume his studies in history.

After graduating from Willamette, Barnes earned a master's in economics from Harvard before deciding to go into journalism. He worked on the copy desk at two other New York papers before joining the Herald Tribune in 1924.

Kluger's book described Barnes as "big, lumbering, painfully earnest" -- a man committed to doing the best job he possibly could, particularly as he learned the ropes of foreign correspondent duty in the Paris bureau.

Among an editorial crew of has-beens, drunks, young expatriate transients on a lark, and a nucleus of able technicians, most of them Britons with French wives, the inexperienced Barnes was intent on mastering his craft -- no small task since he had more or less fast-talked his way onto the staff after a short, shaky start back in New York on the desks of the Brooklyn Eagle and the Evening World.

He was always loaded down with books and papers and magazines, always arguing idealistically in the after-hours talkathons at Harry's New York Bar or Le Dôme. His wickedest outburst was "Golly Moses!" and his worst sin was a tendency to knock things off people's desks as he brushed by them in a coat and jacked loaded to the lapels with heavy-duty reading matter.

Barnes' responsibilities soon expanded, winning him the opportunity to move out of Forrest's shadow and on to cover Europe's three prominent dictators in succession. He headed to the Herald Tribune's Rome bureau in 1930, then Moscow from 1931-35 and finally Berlin from 1935 until he took over the London bureau in March 1939.

He would write of his time in Joseph Stalin's Russia: "Here I'm one of a few observers of what is undoubtedly the most important experiment of this century; and perhaps for several centuries; either for good or bad."

Barnes' wife Esther, a fellow Willamette grad, was by his side throughout, but he finally sent her and the couple's two daughters, Joan and Suzanne, back to the U.S. in June 1940.

By this time, Barnes was back on the continent. He was with German troops when they entered Dunkirk after the British evacuation and reported from Amsterdam and Berlin as German troops rolled across western Europe.

In a story published in mid-June, Barnes predicted Hitler would eventually attack Russia, despite the countries' non-aggression pact. That led the Nazi government to kick Barnes and his colleague Russell Hill out of the country on June 21 for "sending reports which could create difficulty for Germany with other countries." A year and a day later, German troops rolled across the Soviet border as Operation Barbarossa began.

Booted from Berlin, Barnes headed back to Rome and then on to Budapest, Bucharest and eventually to Egypt, where he covered the British campaign in the Western Desert.

In the meantime, Esther became a popular speaker among civic and women's groups in the Salem area, regaling audiences with tales of life in Europe that were faithfully recapped in the women's pages of the local newspapers. In late October, she attended a party with other wives of newspapermen in Salem and told them she found it "perfectly normal" to be separated from her husband for long periods.

"We wives of foreign correspondents just assume it is part of our life," Esther said, according to The Capital Journal. "It amuses me at the way some of you women think it's terrible to be separated from your husbands for a week or so when they are sent on short assignments. Think about how many wives of foreign correspondents feel when their husbands are sent away for years."

It's not clear how much contact she had with her husband at the time. There are occasional mentions in the Salem newspapers throughout 1940 of him sending telegraphs home to at the very least apprise his family of where he was, if they hadn't already found out from datelines on his articles.

Barnes arrived in Athens in November via a British warship, shortly after Italian troops moved into Greece. It was there that he would write his final stories.

On the evening of Nov. 17, Barnes and United Press correspondent Jan Yindrich "drove in brilliant moonlight over winding roads through the Blue Mountains of Greece" to an undisclosed airfield (Tatoi, north of Athens). From there, they were to accompany Royal Air Force crews set to bomb an Albanian port Italy was using as a staging area for its attacks on Greece.

Yindrich described stepping into a "bare whitewashed shed" to get dressed: "I pulled on thick riding breeches, two pairs of socks, one pair of stockings, thick leather knee boots, a fleece-lined waistcoat and a flying jacket called the 'Mae West' because it gives the wearer curves at certain places and keeps him afloat if he falls in the sea."

From there, the men went their separate ways. Barnes climbed aboard a Wellington bomber from 70 Squadron with Pilot Officer William Graham Bennett at the controls and four crew members, all Sergeants: Geoffrey Green, Geoffrey Hawksley, John Palmer-Sambourne and Frederick Savage.

They set a course for Durrës -- Durrazzo, in Italian -- a little over 300 miles away on the Adriatic coast. Later reports would indicate the weather along the coast was "exceedingly bad" that night, and Bennett apparently never found the target. The bomber wandered beyond Durrës and over Yugoslavia, where the cloud cover became so thick that Bennett tried to descend so he could determine his location.

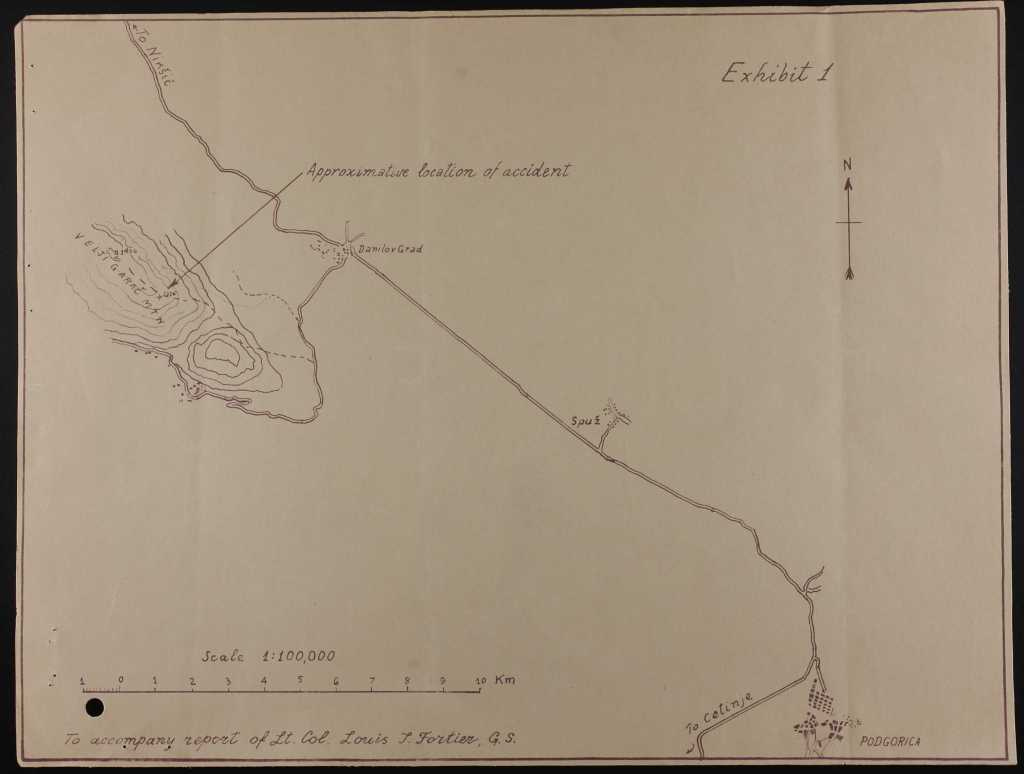

Sometime between 3 and 4 a.m. on Nov. 18, the Wellington -- still fully loaded with ordnance -- flew into the side of a peak called Velji Garač near Danilovgrad in what is now Montenegro. The ensuing explosion was so intense local residents believed they were being bombed, and the scene on the ground was horrific.

A colonel from the Yugoslav army named Sokolovic arrived around 6 a.m. and began investigating. According to a report filed later by U.S. Army Lt. Col. Louis J. Fortier, Sokolovic "picked up the passport of Mr. Ralph W. Barnes lying near a partially dismembered body which was later identified as that of Mr. Barnes."

Arthur B. Lane, the U.S. minister to Yugoslavia, had dispatched his military attache to the scene from Belgrade after learning an American citizen was aboard the plane. Fortier was a World War I veteran who would go on to serve as artillery commander of the 94th Infantry Division and join the intelligence community after the war.

In his report, Fortier would write that the plane "had the bad fortune of striking the highest mountain peak within the general area. Added to the force of the crash came that of the exploding bomb loads upon impact with the side of a stone mountain. The result is about what might have been expected. The plane and its occupants were scattered over a very wide area."

In addition to the hand-drawn depiction above, Fortier's report included a rough map of the crash site showing body parts arrayed across half a kilometer.

Yugoslav officials conducted a full military funeral for the six men lost in the crash on the morning of Nov. 21, and the bodies were buried at a military cemetery next to an airfield in nearby Podgorica. In addition to a sizable military contingent, Fortier estimated thousands of civilians attended the service, which was conducted by a British chaplain based in Belgrade.

He concluded with this:

This report would be incomplete if I failed to attempt to describe at least some of the setting and, I might add, atmosphere surrounding the scene of the tragedy. The Yugoslav Army, civilian officials and peasants were crestfallen at the knowledge that Britishers and, I felt, particularly an American should have been involved in this fatal accident. The cooperation of officials was complete and most sympathetic. At the funeral, thousands of silently weeping men and women lined the streets and road to show their respect.

There were no morbidly curious at the grave. Peasant women added small bunches of wild flowers to the other floral tributes. Buried as he is in the center of the Podgorica plateau, surrounded by the high, rugged mountain region of Montenegro, Barnes does not rest among strangers, but as one native remarked to me, "Tell your countrymen that we shall guard him well and as our own."

After Barnes' body was identified on the morning of Nov. 19, Arthur Lane sent a "RUSH" telegram to the State Department in Washington, which received it at 10:50 a.m. Eastern time.

In Oregon, Esther Barnes was attending a meeting of the first aid committee of the local Red Cross chapter when government officials contacted her mother with the news. Esther's mother then called Barnes' parents to tell them of the tragedy, and word soon got out around Salem.

That evening's Capital Journal ran a banner headline across all eight columns on the front page -- "Crash in Yugoslavia Fatal to Ralph Barnes" -- and the morning Oregon Statesman ran three pieces about Barnes on its cover, including a tribute penned by the Herald Tribune's editor, Ogden Reid. It began:

The last thing that Ralph Barnes would wish would be that his end should be treated as an extraordinary event. It was, in fact, no more and no less than death in the line of duty such as the whole far-flung line of American corespondents face in Europe and around the world.

The reader of a newspaper has little cause to estimate the risks of reporting in modern warfare. It is an elemental part of a correspondent's training to view his own personal adventures as irrelevant and unimportant save as they help to portray the truth. To the responsible heads of a newspaper, as to its staff, such risks in time of war can never be far from minds. For all its great expansion in news coverage, in number of correspondents, a newspaper staff remains a closely knit family, bound by ties of friendship and comradeship beyond any other trade save, perhaps, that of seafaring. The risks are comparable, the common cause grips equally. If there is little room for sentiment, there are ties of affection beyond breaking.

The Herald Tribune editorial concluded by framing correspondents' value in terms that went far beyond mere individual sacrifice to reach the existential:

In stressing the deep personal loss which this paper has sustained we would stress even more the incomparably precious service which such character, such ability, such devotion, daily, hourly, rendered to the American people. If truth survives from the monstrous wreck of Europe first credit will belong to the loyal body of American newspaper correspondents, among whom Ralph Barnes was a shining figure.

As many of the tributes that followed made note, Ralph Barnes was the first U.S. war correspondent to die covering the war. By the time the conflict ended nearly five years later, dozens more would share the same fate, as would still more journalists from numerous other countries.

He was the first, though, a little over a year after the global conflagration began and a little under a year before his own country would officially become involved. Even without the benefit of the context we have decades later, Ralph Barnes' peers had no trouble putting his loss in perspective.

"His life was tragically brief," the Oregon Statesman wrote in an editorial, "yet he lived for a decade at the center of the most momentous events in world history. He helped to write that history."

The men who went down with the Wellington 80 years ago no longer rest in the military cemetery in Podgorica.

After the war, the five RAF airmen were reinterred at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's Belgrade cemetery. Ralph Barnes is now buried at the Florence American Cemetery in Italy.

Esther Barnes and her daughters continued to live in Salem, where Esther would marry widower Chester Downs, a local physician. She died on Nov. 16, 1985, nearly 45 years to the night her first husband climbed aboard a bomber at a Greek airfield.