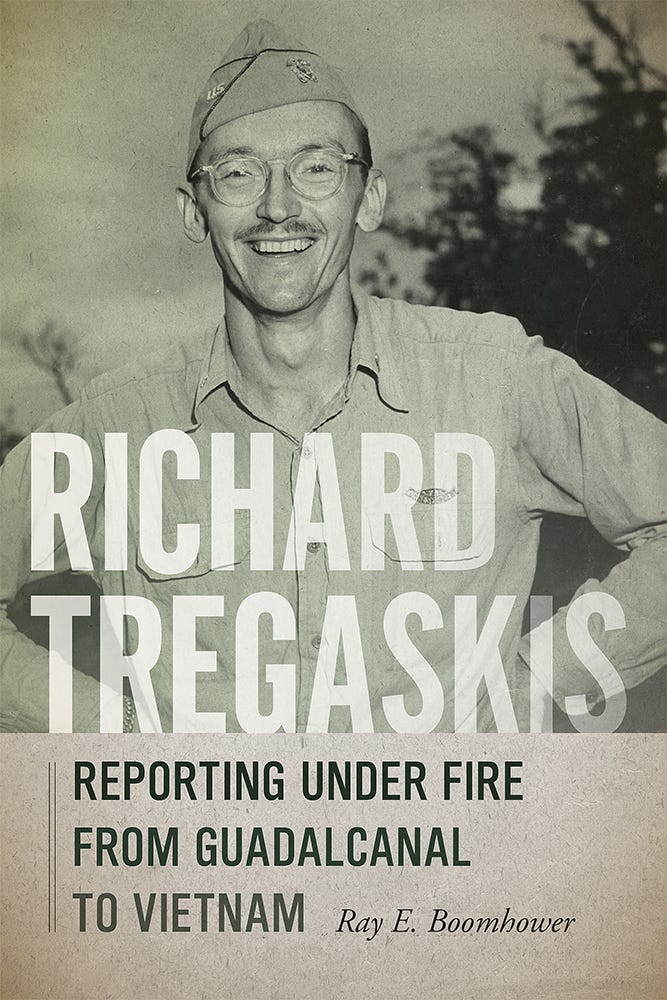

Richard Tregaskis: A new biography of the legendary war correspondent

We’re changing things up a bit today as we take a look at one of the most celebrated correspondents of World War II. Ray E. Boomhower’s latest book, Richard Tregaskis: Reporting Under Fire from Guadalcanal to Vietnam, is now available from the University of New Mexico Press. We spoke with Ray to get his insights on one of the truly legendary journalists of the era and learn a bit about what led him to write the first biography of Tregaskis.

Ray E. Boomhower became interested in journalism as a teenager and attended Indiana University’s high school journalism institute while serving as editor of his school newspaper. He went on to study journalism at IU and work on the Indiana Daily Student while taking numerous classes at Ernie Pyle Hall. After graduation, Boomhower worked for newspapers in Rensselaer and Anderson, Indiana before moving on to the Indiana Historical Society in 1987. He has served in a variety of roles there ever since, taking over as editor of the society’s quarterly magazine Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History in 1999 and also working as a senior editor for the Indiana Historical Society Press.

The author of more than a dozen books, Boomhower has previously written biographies of World War II correspondent Ernie Pyle and Robert Sherrod, which served as a jumping-off point when he was looking around for his next book project back in 2017. He soon settled on Tregaskis, the war correspondent for the International News Service and later the Saturday Evening Post who achieved international fame with the publication of his book Guadalcanal Diary in January 1943.

Ray E. Boomhower: “It seemed logical enough to kind of complete this, what I'm calling my war correspondent trilogy, by looking at the career of Richard Tregaskis. I'd been a fan of his writing -- I read Guadalcanal Diary in high school. And I was also fascinated by the war, the Pacific theater for some reason, I think it's because I'm just impressed by the great distances involved in getting to battle. So he seemed like a natural subject for this book, and I was lucky enough to get it published by the University of New Mexico Press.

In addition to combing through Tregaskis’s published stories in online newspaper archives, Boomhower received a grant from the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation to help fund his research and visited the two major archives that hold Tregaskis’s papers: the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University and the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. He was fortunate enough to finish his in-person research before COVID-19 shut down public access to many archives.

Boomhower: “I made a discovery that I didn't know I was going to have, and that is he had started a memoir about his life in World War II, and gotten up to, I think, headed out to Guadalcanal, and then kind of sketched out what the next chapters were going to be, but never really finished it. But it was a great help in looking at his early experiences during the war, which were just fascinating to me.

“I'd not known that he had been in on all these really major turning points in the war in the Pacific early on. He was there watching from the [cruiser USS] Northampton, when the Doolittle raiders took off from the Hornet to bomb Tokyo. Then he transferred to the Hornet and was on it when it was kind of circling around during the Battle of the Coral Sea. But he was also on board when it participated in the Battle of Midway. He watched the planes fly off, including Torpedo Squadron 8, which was decimated in the attack on the Japanese fleet with only one of its squadron mates, George Gay, surviving the engagement. So a lot of fascinating detail that I didn't know about before I went to the archives to do my research.”

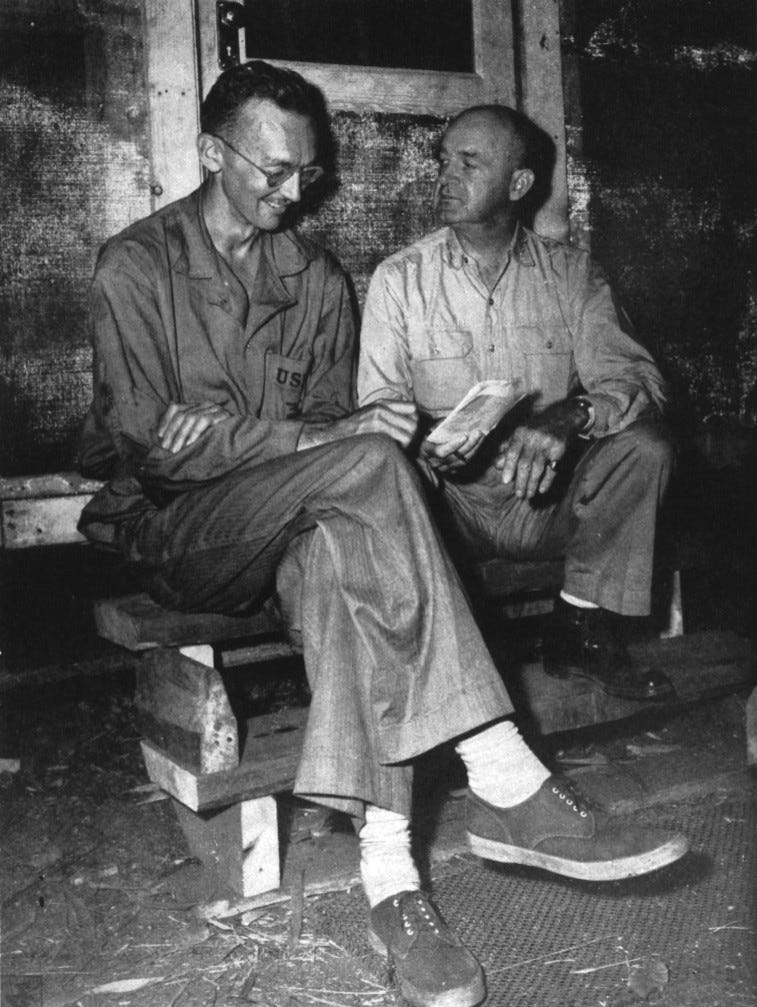

Born November 28, 1916, Richard Tregaskis grew up in New Jersey and attended Harvard, where he began his journalism career working for the Hearst newspapers in Boston. Tregaskis eventually joined the International News Service in New York. After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Tregaskis tried to join the military but was rejected because he was considered too tall (about 6-foot-6) and had poor eyesight. He also learned around this time that he was diabetic, but he kept that revelation secret from all but his family because he was afraid his bosses at INS would not let him go overseas to cover the war if they knew. And covering the war was Tregaskis’s primary goal once it became clear he could not join the fight firsthand.

Boomhower: “He wanted to do something for the war effort. I think that's something that a lot of American men felt at that time, with the great anger about the attack on Pearl Harbor, and this was a way that he could do it with his typewriter, going to the front lines and letting people know about the sacrifices of the men at the front. I came across an anecdote he wrote about a soldier who said, ‘Why are you here? You don't have to be here, why are you here?’ He said, ‘Well, of course I have to be here -- this is where my job is.’ And he did it very well.”

Tregaskis shipped out to the Pacific in the spring of 1942 and spent his first few months covering the Navy, but his big break came during the first major U.S. land operations of the war. He landed with the Marines on Guadalcanal on August 7 and ended up remaining there through September 26. He and Bob Miller of United Press were the only correspondents on Guadalcanal for the long haul, and they endured all of the hazards the Marines did. Along the way, they filed stories about the fighting and life on the island back to their respective wire services, but Tregaskis had bigger plans.

Boomhower: “It always seemed to me that he had the idea that, I'm going to get a book out of this experience. He's there for seven weeks and decides, I've been here long enough, time to go and get started on this book. Just getting off the island was difficult enough; he had to fly out on a B-17 bomber and get to New Caledonia. He kind of sets up shop there to start on this book, but then has to deal with the effects of what he'd undergone the last seven weeks. Today we would call it PTSD, but they didn't know that term back then. He had to steady his nerves in order to get down to the business of writing.”

Once he got started, Tregaskis plowed his way to completion — even improvising a place to set up his typewriter on the long B-24 flight across the Pacific back to Honolulu. Once there, Navy censors checked his copy daily and locked up his notes in a safe overnight because they contained sensitive information about numerous operations that had not yet been made public. Tregaskis wrote at a furious pace, turning in 80,000 words to INS on November 1, 1942.

Boomhower: “He was used to working hard. He was not afraid of hard work. He had, from an early age, kind of hustled to make a name for himself in journalism, to help pay for his schooling, not only at the private academies he attended when he was in New Jersey, but also at Harvard, as well, where he was working as kind of a correspondent for the Boston newspapers. And then getting a job after college, hustling, writing everything from hard news to feature stories and always looking for that next step up the rung of the ladder of journalism and getting a job with INS after that. So he's someone who wanted to make a name for himself and was able to do so with his war reporting.”

The book Tregaskis had just completed would do exactly that. INS sent the manuscript to nine publishers and Bennett Cerf of Random House jumped on it immediately, securing the rights. After another round of checks by military censors, Guadalcanal Diary was rushed to publication and released on January 18, 1943 to rave reviews, quickly becoming a best-seller. One reviewer described its portrayal of the fighting man’s day-to-day life as “The long letter home we have longed for.” Tregaskis was back in the Pacific by February, but his life was changing.

Boomhower: “Fame opens a lot of doors for you when you're a correspondent. I don't think he expected that kind of fame to come. I know he wanted to get the book out and get it published and was happy to get it published, and hoped that it might make enough money to help his family out with some of their financial problems. I don't think he expected it to be as well-known as it became, but it did. Even though it became famous, and Hollywood made it into into a movie, he was still stuck out there in the Pacific, doing his work for the INS, they still expected him to write his dispatches and get them home.”

In mid-1943, Tregaskis got a change of scenery, leaving the Pacific and heading to Sicily to cover the fighting there. He landed in Salerno in early September and spent the next couple of months chronicling the arduous slog that was the Allies’ move into Italy. On November 22, Tregaskis was with Darby’s Rangers when a piece of shrapnel from a German shell pierced his helmet and partially penetrated his skull. An Army surgeon spent four hours operating on him with Tregaskis under local anesthesia, removing a dozen bone and shell fragments from the correspondent’s brain. Surgeons back in the U.S. eventually used a metal plate to cover the wound, but Tregaskis didn’t let it slow him down. He wrote a book about his experiences in Sicily and Italy called Invasion Diary and returned to Europe in late July 1944.

Boomhower: “I'd been influenced, of course, by reading Guadalcanal Diary early on, but I discovered that I like Invasion Diary even more than Guadalcanal Diary. I think his writing is more nuanced. I think he's a better writer. It's a second book, so I think you're a little bit better on your second book than maybe your first, and he really writes very evocatively about his wounding, his experiences in being wounded. What happens after his wounding, his time in various military hospitals. It's very effective writing.

“He's not someone who's telling the big, strategic picture of what's going on in the war in the Pacific or the war in Europe. In selecting the diary format, you get a good sense of what life was like day by day for those who were involved in combat, and he's there with them. I've always marveled that he wasn't killed earlier in the Pacific, because it seems that he was always there, near the front lines, willing to go on dangerous raids with [USMC Col. Merritt] Edson's men on Guadalcanal. And he had a number of times where he was under fire from Japanese ships offshore that he'd get off the ship and that night, it'd be bombed and sunk by the Japanese. And if he had stayed on instead of going to shore, he might have been killed. So it’s just these near-misses and of course his number nearly came up in Italy, because he's once again out among the men trying to report on the battle, as near as he could.”

Even after being wounded, Tregaskis didn’t try to play it safe. He covered the brutal house-to-house fighting in Aaachen, eventually turning his experiences there into his first novel, 1945’s Stronger Than Fear. His INS colleague Robert Considine said of Tregaskis, “He didn’t believe in communiques — he had to see it for himself.” That addiction to being close to the front lines is a running theme in Boomhower’s book.

Boomhower: “Action is is sort of like a drug. It gets into your veins and it's hard to stop once you're addicted to it like he was. There's that quote I use as the epigraph to the book, it's from Invasion Diary. He said: 'The lure of the front is like an opiate. After abstinence and the tedium of workaday life, its attraction becomes more and more insistent, perhaps the hazards of battle, perhaps the danger itself, stir the imagination and give transcendent meanings to things ordinarily taken for granted.' So, even at the time, while he's going into action, he realizes that this is something powerful and it has an effect on him and draws him even when he knows that there is danger involved.”

Tregaskis left INS in 1945 and went to work for the Saturday Evening Post, where he wrote a series following the crew of a new B-29 bomber from the U.S. to Guam. He flew missions with that crew and also went up in an Avenger torpedo bomber off the USS Ticonderoga. Tregaskis was in Manila when Japan surrendered in August 1945 and covered Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s military government in Tokyo.

Boomhower’s book delves into the details of all of Tregaskis’s experiences covering the war, drawing upon a rich selection of writing from the correspondent himself. It also goes on to chronicle his later life as a freelance writer and author who would make multiple reporting trips to Vietnam beginning in the fall of 1962.

Richard Tregaskis is an in-depth and long-overdue portrait of a preeminent World War II correspondent, one of the few journalists to spend significant time covering both the Pacific and European theaters. If you enjoy the work we do here, we have no doubt you will enjoy this book. Thank you Ray for taking the time to speak with us about it.