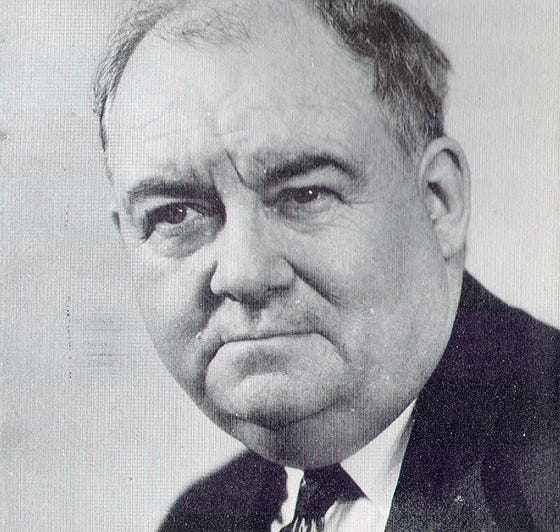

Robert J. Casey's five years of war

Robert J. Casey was 51 years old when the United States entered World War II, and he had already fought his battles, but nothing would keep him from covering the most important story in the world.

Casey was on assignment in Alaska on Dec. 7, 1941, when news of the attack on Pearl Harbor arrived. Two weeks later, he was in Honolulu. His first story for the Chicago Daily News from the shaken territorial capital, datelined Dec. 21, began like this:

Some 2,500 funerals are finished. Temporarily, at least, there seems to be an end to murder in paradise. And, visiting skeptics are pleased to report, this front-line outpost of the United States is getting on with the war.

That lead is Casey in a nutshell — conversational but evocative. It was a style he had employed in Europe to tell the story of the opening months of the Second World War to American readers and would now do so again as the conflict expanded.

Born March 14, 1890 in South Dakota, Casey worked for newspapers in Des Moines, Houston and Chicago before serving as an artillery officer in the Great War, where he saw combat at Verdun and in the Meuse-Argonne campaign. He resumed his journalism career upon returning from Europe and in 1920 joined the Daily News, establishing himself in the years to come as one of the great foreign correspondents of his era.

Days after Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, the Daily News announced Casey would be flying to London to help supplement the syndicate’s war coverage. His first dispatch, datelined Sept. 18, described a prayer vigil in Westminster Abbey.

Thus began more than five years spent writing almost entirely about the war. In addition to his hundreds of newspaper pieces printed before the final surrender documents were signed, Casey would also publish three books about the war between 1941 and 1945.

He was with French army troops when Hitler’s invasion of France and the Low Countries began in territory familiar to the correspondent and those who had fought there a generation earlier. He led his May 10, 1940 story this way:

The war came back to the western front this morning with air raids on the border cities, a promiscuous rain of bombs on schools and apartment buildings and suburban villas, a slaughter of women and children in Nancy.

At this writing, the fighting is well underway in the north, the youth of Holland are lying across machine guns in the tulip beds. Belgium is defending the same old line, and Adolf Hitler’s troops are marching across Luxembourg toward the French awaiting them in the Maginot Line.

Tomorrow, one may hear more of these things and they may be considered in something of their real importance. Today, this region, shaken by a ghastly night, is concerned chiefly with its own dead, clearing the wreckage from its streets, and counting the hours until the time when it will be dark enough for the Nazi dynamiters to strike again.

A little over a month later, Casey described the unthinkable: the final hours of the evacuation of Paris.

The world knows enough about what refugees look like on the march to know what the end of this trail looked like.

After the people with suitcases came the lame and halt and blind, bicyclists with duffel bags on their backs, walking cyclists who used their machines only as pushcarts for bundles. And so they went, all the day, none of them alarmed at the situation, none of them, apparently, much annoyed at having to meet it.

There seemed no reason why one might not stay on here in this quiet, peaceful city forever. Then the hotel closed. Suddenly somebody shut down the remaining cable.

You took a last look at the sun on the domes of the Sacre Coeur and packed your bags. It wasn’t much like Paris as you drove out toward the Porte St. Cloud — yawning streets and shuttered shops and vacant terraces. And yet it was entirely like Paris.

Like many of those refugees, Casey would return to France four years later. He watched the opening salvos of D-Day from offshore, aboard a Royal Navy motor launch, but would eventually go ashore to cover the fighting in Normandy.

He returned to Paris in August and crossed the Siegfried Line into Germany in September, one last milestone before returning home. Casey sailed from Liverpool on Oct. 15 and arrived in Boston six days later.

Casey’s wife Marie, who had been in poor health for years, died of a heart attack in early January 1945 at age 48. Casey spent the rest of the war stateside, doing a series of speaking engagements about his experiences covering the war and continuing to write for the Daily News.

He remarried in 1946 and retired the following year, though he continued to churn out books and newspaper pieces for years. Casey died Dec. 5, 1962, after being hospitalized about two weeks earlier following a stroke.

In a tribute piece published days later, the celebrated screenwriter Ben Hecht — a former Daily News colleague — wrote this about his friend’s wartime work:

There were many fine and mobile correspondents covering the war for our American press. But I don’t think any of them, not even Quentin Reynolds, ever achieved the Casey mileage, or ever stuck his nose into so many varied spots of confusion and danger.

Up in planes, down in submarines, off on lone treks into dales and deserts, Bob Casey pumped more news out of the war and its aftermath. He reported battles, water spouts, sunsets, tribal dances, starving families, personalities, hysteria, incompetence and courage.

And one more thing was usually in his reports — his own Chicago reporter version of all he beheld. It was a version that saw the comic, cock-eyed overtones of events, however big they were; and of people, however mighty their importance.