Robert Losey, the first U.S. serviceman killed in World War II

On April 21, 1940, U.S. military attache Robert M. Losey became the first American serviceman to die during World War II. This story originally ran on my website The Low Stone Wall, which pays tribute to Americans killed during the war.

As the U.S. space program blossomed in the 1960s, NASA officials settled on a certain profile as they screened astronaut candidates.

First and foremost, they needed elite pilots -- those who had proven in combat or in testing new aircraft that they could handle any scenario that might arise miles above the earth. But they also preferred men whose aviation skills came with strong scientific underpinnings, ideally including advanced academic degrees.

Had he been born a quarter-century later, Robert M. Losey might have had a resume that stacked up well against any of the men who became household names to future generations.

A West Point graduate who later earned two master's degrees from Caltech, Losey was clearly on the fast track in the Army Air Corps as the political situation in Europe deteriorated in the late 1930s. Already under the wing of Gen. Henry "Hap" Arnold as a staffer in Washington, Losey seemed destined to play a critical role in the inevitable conflict over the horizon.

If given a chance, we might know his name decades later for his impact on the war, rather than the historical footnote he became: the first American service member killed in World War II.

Robert Moffatt Losey was born May 27, 1908 in Andrew, Iowa, but he rarely stayed stationary for long.

His father, Leon, was a Presbyterian clergyman and seemingly always on the move from one congregation to the next. Born in Pennsylvania in 1880, Leon graduated from Princeton University in 1907 and married the former Nellie Moore on June 13 of that year.

The following spring saw the Loseys relocate to Iowa, where Leon was the pastor of the Presbyterian church in Andrew for a little over four months. The family packed up to move back east when Robert was about three months old, settling in Esperance, New York. Late in 1910, they headed west across Upstate New York to Auburn, where Leon would study at the seminary before being selected as pastor at the city's Westminster Presbyterian church.

The family moved again in 1915, to tiny Preble, New York, then moved on to Byron, near Rochester, a few years later, before Leon took a job with the Interchurch World Movement in 1919. That position kept Leon traveling regularly, and after the organization disbanded in 1920 the family ended up in Basin, Wyoming, and then in Terry, Montana, by January of 1922.

In early July 1923, Leon was admitted to a hospital in Miles City, Montana, after complaining of abdominal pain, but he arrived too late. His appendix had burst, and he died July 8 at age 43.

After her husband's funeral, Nellie decided to return to her native New Jersey with Robert and his sister Margaret, settling in Trenton. Robert graduated from Central High School in 1924 and was accepted at West Point the following year, with the idea of becoming a pilot already firm in his mind.

His entry in the academy's 1929 yearbook hints at his future as an innovator with wide-ranging interests: "We thus see in him a fine disregard for useless restrictions, a spirit not easily rebuffed, a wide interest in science. Bob carries with him into the Service not only these qualities, but as well a love of sport that has made him an authority on football and golf, an assortment of hobbies and accomplishments, and an aspiration for the Air Corps."

Initially assigned to field artillery following his graduation from West Point on June 13, 1929, Losey realized his dream with a transfer to the Air Corps three months later.

2nd Lt. Losey completed primary and advanced flight school in 1930, the latter on a pursuit course. With that training in fighter planes under his belt, Losey was assigned to the 77th Pursuit Squadron based at Mather Field near Sacramento.

The unit transferred to Barksdale Field in Louisiana in the fall of 1932, and Losey arrived in a leadership role. He was named post ordnance officer and assistant post adjutant in early November, The Times of Shreveport noted in one of several mentions of Losey during his time at Barksdale.

The following month, Losey was one of six pilots from Barksdale selected for what became a 6,000-mile adventure: ferrying 17 planes across Central America to the Canal Zone in Panama. Departing from Kelly Field in San Antonio on Dec. 15, the group stopped in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica on the way to the Canal Zone, celebrated along the way with banquets in each city.

The planes delivered, the fliers boarded the SS Cristobal in Panama on Jan. 15, 1933, and arrived in New York eight days later. From there the Barksdale group boarded a transport plane at Mitchel Field on Long Island and flew home with stops in Virginia, North Carolina and Alabama before arriving back in Louisiana on Jan. 28.

On April 10 of that year, Losey married Kathryn "Kay" Banta in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Kay was plenty familiar with the military lifestyle, as her father William was an Army surgeon who retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1918 due to a disability suffered in the line of duty. Born on an Army base in Wyoming, Kay was raised mostly in Los Angeles and attended UCLA. She was previously married to a Navy officer, Joseph F. Mallach, in 1928, but the pair had divorced.

Kay's desire to get back to her hometown might have played a role in Losey's next career move.

During the early 1930s, the Army recognized the need to allocate more resources to one critical component of the aviation program that had been neglected in the focus on aircraft development: the weather.

A contemporary of Losey's, Arthur Merewether, recounted the situation in a 1991 interview for the American Meteorological Society:

"At the time when I came in the Army Air Corps, there was only one other meteorologist and that was Pinky Williams. He had set up an experimental station at Langley Field in Virginia to try to find out how many people should be assigned to meteorology and what their particular jobs would be -- how many forecasters, how many observers, etc. That's how the Weather Service in the Army got started. Then they decided that they ought to start training some meteorologists, so they selected me to go to MIT and take the weather course, and they selected Robert Losey to take the course at Caltech."

So it was off to Pasadena for the Loseys in time for the start of classes in September 1934. He completed a master's in meteorology the following spring and was assigned to March Field in Riverside, California, as meteorology officer in May 1935. Losey returned to Caltech a year later to double down with a further master's in aeronautical engineering. His thesis, completed in 1937, was titled: "A Theoretical Investigation of the Possibilities of Internal Cooling of Aircraft Engines by Water Injection to the Cylinder".

Col. Henry "Hap" Arnold was the base commander at March Field during Losey's time there, and he recognized the potential in the aviator-meteorologist. Arnold was assigned to the Air Corps headquarters in Washington in 1936 and summoned Losey to join him in D.C. the following year and formalize the service's meteorology operations as the first chief of the Weather Service.

"He was a favorite of Arnold's," Lt. Gen. William O. Senter said of Losey in a 1986 oral history interview, via John Fuller's book Thor's Legions. Senter said Losey was "a very confident officer ... he put together the Weather Service program all by himself."

One of the weather service's areas of interest was the study of how planes would operate in combat in cold-weather conditions. When the Soviet Union invaded Finland in November 1939, the U.S. military saw an opportunity to send an expert observer in the form of Losey, now a captain, for a first-hand look. As a later United Press report put it:

"His presence in Finland gave the Army its first chance to study actual warfare in temperatures from 25 to 50 degrees below zero since the World War campaign at Archangel in 1917. Air Corps officials especially desired expert data on the performance of planes, motors, tanks, guns and other equipment at the low temperatures."

On Jan. 17, 1940, Losey stepped down as chief of the Weather Service, handing the reins over to his handpicked successor, Arthur Merewether, as he was named assistant military and air attache to Finland. Kay Losey stayed behind in D.C. at the couple's apartment at 2222 I Street NW (now a George Washington University residence hall) as her husband headed to Europe.

Losey jumped right into his work upon arrival in Finland, compiling confidential reports on the performance of Soviet aircraft and other equipment in sub-zero temperatures before the "Winter War" ended in a cease fire agreement on March 13.

But peace in Scandinavia was short-lived. On April 9, after weeks of mounting tensions, Germany invaded Norway and Denmark. As hostilities in the region escalated, Losey was sent to Stockholm to monitor the situation along with other U.S. officials there. But he was soon detailed to assist the U.S. minister to Norway, Florence Jaffray Harriman, in ensuring both her safety and that of family members of American diplomats who had fled Oslo after the invasion.

Harriman wrote in her 1941 memoir "Mission to the North" that her instructions were to "follow the government" of King Haakon VII, which had also fled Oslo and headed north along with members of the British and French consulates. As she did that, she sent the American evacuees farther ahead, to the Lillehammer area.

Three days later, Harriman crossed the border into Sweden near Höljes and was finally able to contact her counterpart in Stockholm, Frederick A. Sterling. He informed Harriman that Losey was en route to join her and should arrive late that night or early the following morning.

The minister ran into Losey on the way to breakfast the next day and recorded her first impression in her diary: "The new military attache is a nice, spare young man in a flying corps uniform, and seems in every way acceptable."

They traveled north to Särna that day, April 13, and at lunch the following day, Harriman wrote, Losey was "ready to press on to Lillehammer," back across the border, to check on the status of the evacuees from the consulate. She agreed to let him depart as she also was eager for news on their situation.

Losey and Harriman's driver, Lars Fröislie, returned on the 16th, having been unable to make contact with the American party due to snow blocking the mountain roads. But Losey had encountered Norwegian Gen. Hvinden Haug and brought back information about troop movements that he wanted to report back, so he drove on to Stockholm to deliver the information directly to Sterling, then took a train back to rejoin Harriman the following evening.

The pair decided to head back into Norway, and packed up the car once again to do so. Along the way, they discussed whether Harriman should join Losey on the entire journey to Dombås, with the attache arguing against it.

"You might be bombed," he said, according to her memoir. "The Germans are strafing the roads."

"But so might you," she replied, "and that would be worse for you are young and have your life before you, while I have had a wonderful life and nearly all of it behind me."

"I certainly don't want to be killed," he said, "but your death would be the more serious as it might involve our country in all kinds of trouble, whereas with a military attache..."

She eventually agreed to stay behind, sending Losey on along with Fröislie, an American flag tied to the top of the car in an effort to deter German attack. "I will cheer when they return," Harriman wrote in her diary.

Late on Sunday, April 21, she received word from Lt. Cmdr. Ole Olsen Hagen, Sterling's naval attache, that he had escorted the American consulate contingent safely across the border at Fjällnäs, Sweden. While overjoyed by the news, Harriman was concerned she had not heard back from Losey, writing in her diary: "Uneasy. No report from the captain."

Losey and Lars Fröislie had made their way to Dombås, northwest of Lillehammer, unaware that the Americans they sought already had passed through the town in their escape. As the pair discussed their next move at the Dombås train station, German planes appeared overhead and began bombing and strafing the rail juncture. Everyone present ran for the tunnel carved out of a nearby hill for cover.

While others at the scene ran deeper into the tunnel or pressed themselves against its walls for protection, Losey felt compelled to get a glimpse of the Luftwaffe planes as they attacked. He was standing about 30 feet inside the tunnel when a bomb hit near the entrance and a piece of shrapnel flew through the air and pierced his chest, killing him instantly.

Word of Losey's death first reached Frederick Sterling in Stockholm around midday on the 22nd. He immediately cabled the State Department in Washington saying he had received word from a Major Yasum, "presumably a Norwegian military officer," that Losey had been killed in a German air attack. The message said Losey's body would be sent on to Fjällnäs via train, where Sterling ordered Hagen to take charge of the remains.

Sterling also called Harriman to share word of Losey's fate.

"The news was a horrible shock," she wrote later. "All day we had been expecting him. Our sense of loss in the world was centered in that one young American."

Losey's coffin was draped with the same flag he had tied to the roof of the car in hopes that it would keep him safe.

Losey's death was front-page news across the United States, from The New York Times to small-town dailies. The growing global conflict finally had reached one of America's own.

Kay Losey was at her parents' home in Hollywood when informed of her husband's death. According to media reports, she collapsed upon hearing the news. "It's a war, and I guess you can expect anything," she was quoted as saying.

The Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, requested a full report on details of Losey's death, but no diplomatic action was taken. Germany's military attache to Washington, Lt. Gen. Friedrich von Boetticher, visited Hap Arnold at the War Department a few days later to pass along a message of regret and sympathy from Hermann Göring, the German air minister.

A small memorial service for Losey was held in Stockholm on April 26, with Harriman, Sterling, and other diplomats from around the world in attendance. A British chaplain conducted the service, and the organist played Chopin's Funeral March.

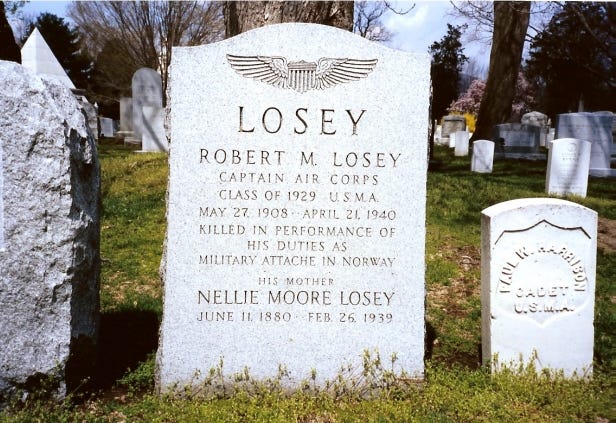

Losey's body was cremated and his ashes returned to Boston the following month aboard the SS Exeter,delivered by the Paris-based American diplomat Benjamin Hulley. They were then flown to West Point, where funeral services were held May 29 with his widow in attendance. Losey's remains are buried with his mother's at the academy's cemetery.

While Losey's Air Corps comrades soon turned their full attention to the war, his legacy lived on.

In August, Hap Arnold announced that the Army would conduct extensive cold-weather flying tests at a new $7 million base in Fairbanks, Alaska, beginning in November 1940. Reports on Arnold's announcement said initial testing would be based on observations sent back to Washington by Losey from his time in Finland.

Late that year, the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences inaugurated the Robert M. Losey Award, with MIT professor Henry G. Houghton selected in January 1941 as its first recipient. The award has been given out annually ever since in recognition of "outstanding contributions to the atmospheric sciences as applied to the advancement of aeronautics and astronautics." Losey's successor at the Air Corps Weather Service, Art Merewether, was the 1961 recipient.

In May 1941, the War Department announced that a new airbase near Ponce, Puerto Rico, would be named Losey Field. Kay Losey visited the airfield in August. The base was renamed Fort Allen in 1950 and became the home of the Puerto Rico National Guard in 1983.

A Washington Post editorial published two days after Losey's death attempted to put his loss into perspective.

"In a very real and poignant sense Capt. Losey's death symbolizes the larger tragedy of Norway. Like Capt. Losey, the people of that country wanted only to pursue peaceful and humanitarian objectives. They had no desire or intention of getting involved in the conflict. But the war lords in Berlin had other plans and Norway, a land which had been free of invasion for centuries, is today a grim battlefield. Capt. Losey's is thus only one of countless lives which have been and are being sacrificed to Hitler's ambitions."

With millions more still to come.