Correspondent Jack Thompson parachutes into Sicily

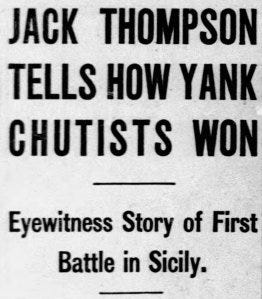

The Chicago Tribune ran one photograph on the front page of its July 12, 1943 edition, a day after the Trib and newspapers worldwide had first reported on the Allied landings in Sicily.

The picture in question was a one-column cutout of Tribune war correspondent John Hall "Jack" Thompson, dressed in paratrooper gear. The headline above it read "Sky Writer". Though it would be four more days before Thompson's first dispatch from Sicily made it into print, the Tribune wasted no time promoting its coup in having one of its own land with the first troops as the Western allies jumped from North Africa back to Europe.

Accompanying the photo on page one was a pre-written Thompson piece outlining what he expected to happen as Allied troops crossed the Mediterranean. Datelines were an art form in and of themselves among war correspondents, and this one told quite a story: "WITH U.S. PARATROOPS BOUND FOR SICILY, July 9".

The report began: "Before midnight tonight the greatest force of airborne troops ever launched by the United States army will be settling over the face of Sicily spearheading an invasion by amphibious troops which is scheduled to follow about four hours later. ...

"This paratroop combat team now undoubtedly is fighting hard at the rear of the enemy as you read these lines."

It took a few hundred more words before Thompson got to his role in the story.

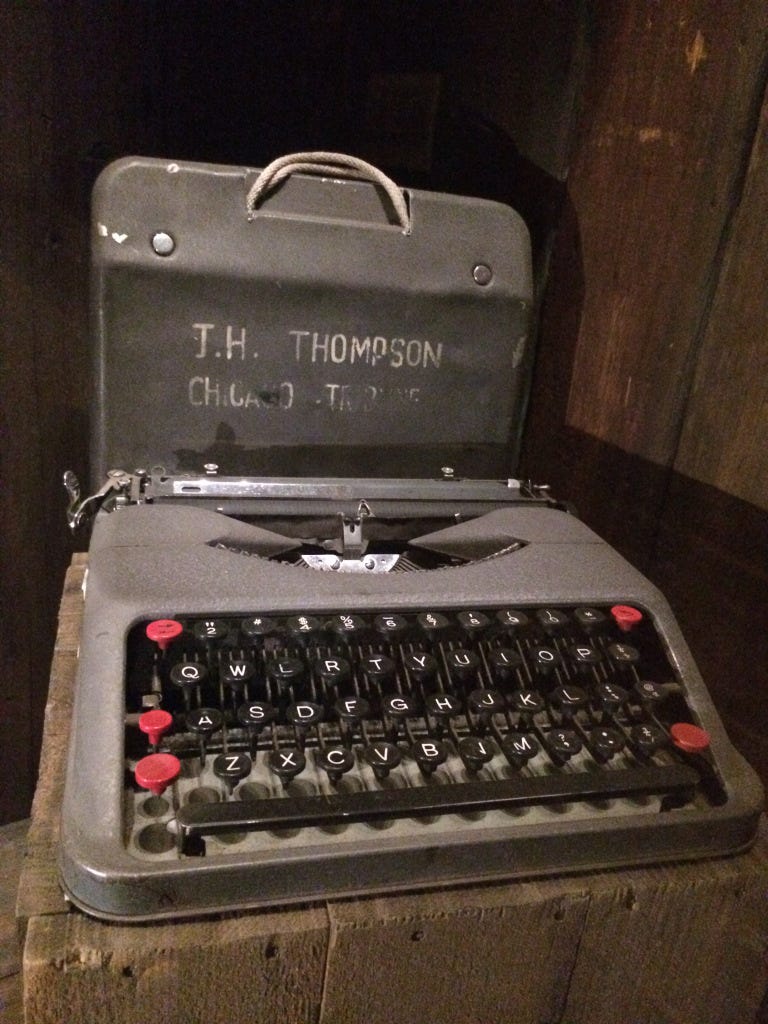

This reporter will be the first American newspaper man to reach Sicily. Future dispatches will be written on a typewriter dropped from a separate parachute, providing, of course, the machine is not broken in its fall.

That machine did in fact survive the jump unscathed, leaving Thompson to lug what he later described as "a second hand portable weighing at least 15 pounds" around the island.

But what a story he was in position to tell.

According to Lloyd Wendt's 1979 book Chicago Tribune: The Rise of a Great American Newspaper, Thompson owed his coveted spot to Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway of the 82nd Airborne, who had requested the Tribune man accompany his forces. Unlike just about anyone else in the press corps, Thompson could claim some experience.

The previous fall in North Africa, he had jumped with Lt. Col. Edson Raff of the 82nd's 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion under what were considered combat conditions -- but the paratroopers landed at an airfield to find it had already been secured by French troops. Still, making that trip was enough to secure Thompson the esteem of his colleagues as the first correspondent to jump into a battle zone.

The experience was harrowing enough that Thompson vowed not to do it again, but the Sicily opportunity was too tempting to pass up:

Here was a chance to be the first American newsman in Sicily and the only one to procure an eyewitness story of the greatest airborne effort and what promised to be a hot fight. My answer to this request was "yes," while some pixie in my brain cells kept yammering in an undertone, "Don't be a --- fool."

Thompson spent the next 10 days living with the paratroopers of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, led by Col. James Gavin, as they made their final preparations for the operation. Thompson didn't directly name Gavin in his initial dispatches, referring to him obliquely in a piece printed more than a week after the jump that switched between first and second person:

As you learned the impending operations in detail by sitting in on all staff conferences, you became aware more and more how the entire combat team reflected the personality of its commander, a quiet spoken, slender "Slim Jim," whose deep set eyes could crinkle with smiles or become intense with decision.

At 35, Thompson was about a year and a half younger than Gavin, who was on his way to winning acclaim as a senior officer who insisted upon jumping into combat with his men. Thompson appeared older than his years, thanks largely to his famous beard. Commented upon in nearly every mention of him by colleagues for the rest of his life, it had quickly earned him the nickname "Beaver" and made him one of the more recognizable members of the press corps.

The story Thompson filed after he returned safely from Sicily to North Africa was an opus by newspaper standards. Running about 2,000 words, it began on the front page of the July 16 Tribune and the conclusion and a sidebar filled up almost all of page 4. Even then, Thompson didn't feel he had really scratched the surface. His fourth paragraph reads:

It would take a book to tell the full story of this operation and it will be days before all details are even learned, for almost every man who jumped did a job worth of an army medal. But this much at least can be told by a correspondent who jumped with them to make his second combat jump, and this by night.

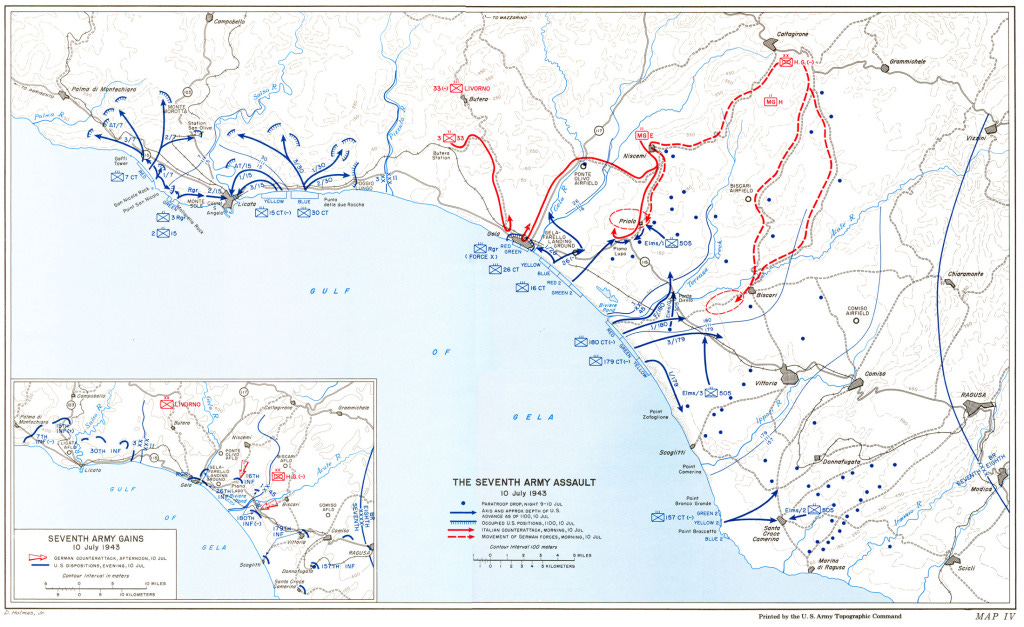

The account doesn't hesitate before getting to the salient point: the paratroopers ended up landing nowhere near their drop zones. Thompson estimates the entire team ended up 30 to 50 miles from their objectives, and in widely scattered bunches. That reality forced the commanders on the ground to improvise, assembling ad hoc units and making tactical decisions on the fly.

Thompson was the last man in line to jump from his plane, and he acknowledged in the account printed July 19 that he wasn't relishing the opportunity as the moment neared.

Frankly, my heart was now in my mouth. (Lt. Col. William T.) Rider asked how I was. With an effort I swallowed, grinned and said "all right," knowing it was a lie. Again the co-pilot came into the cabin to report it would be ten more minutes. This was beginning to be a war of nerves.

Soon, however, the light by the doorway turned red and Thompson joined the rush toward the exit, following Rider into the sky at six or seven hundred feet: "The propeller blast caught me with a roar as I dropped into the darkness, turning slightly onto my back."

Unlike his previous jump in Africa, his landing this time wasn't smooth.

Just 30 feet above ground the wind swung me out horizontal and on a back swing I smashed into a tree and onto the ground, landing on my right knee. Branches stung the back of my neck and tore a rib muscle, an injury which did not appear, however, for two days, when I thought I had cracked a rib. My left hand was skinned and cut slightly but the most painful injury was a wrenched right knee.

(That rough landing ended up qualifying Thompson for a Purple Heart, which he received in November 1943.)

As Thompson got his bearings, he noticed a figure moving nearby and reached for the knife that qualified as the only weapon he had carried into hostile territory.

I decided I had better unloosen my trench knife to defend myself if attacked, since the enemy would not know I was a correspondent.

The other man turned out to be a U.S. medic -- also armed only with a knife -- and the two relieved noncombatants joined forces and set out to try and find more friendly faces.

By daylight, Thompson and the medic moved among a group of 25 "assorted troopers" who soon set out for Vittoria. They reached the outskirts of town the following morning after a trek that took its toll on the correspondent, "who had seldom walked more than two miles at a time at home."

Thompson's party eventually caught up with Gavin, who was headed up the road toward Gela. Though not mentioned by name in Thompson's accounts, Gavin's group ended up taking positions on Biazzo Ridge, where they dug in against what turned out to be elements of the Hermann Göring Division. The German forces included Tiger tanks, prompting Gavin to send a runner to headquarters demanding more firepower to augment his lightly armed troopers.

Thompson observed the action "some 100 yards to the rear sheltered by a culvert while the roar of enemy tank engines grew louder." The Germans didn't press the attack right away, and reinforcements eventually arrived in the form of Allied artillery and armor, to the relief of those on the ridge.

Then, like in the last minutes of a Hollywood ending, came our Gen. Sherman tanks and some half-tracks towing anti-tank guns. You could hear the parachute troopers' cheers even above the clatter of the tanks.

German forces eventually withdrew as night fell, with Gavin's forces having held their ground. They soon found that the Germans had pulled out of the sector altogether.

"We counted many dead and wounded, but it was a victory beyond question," Thompson wrote near the end of his dispatch, which concluded:

That was yesterday, and today the men are resting, reorganizing, and often eating for the first time. You find during the fierce throb of battle that hunger is nonexistent, but it comes back once you've had a chance to relax.

An Associated Press story released the day of the attack said 54 correspondents and photographers were scheduled to accompany the invasion -- the largest press contingent to date for an Allied operation.

The majority were assigned to naval forces, watching the action from offshore, with only a select few getting the type of frontline access Thompson enjoyed. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had briefed the press on the upcoming attack nearly a month ahead of time, would follow a similar blueprint for future operations.

Thompson had earned his spot as one of the chosen, and would retain his status throughout the war. He landed on Omaha Beach with the 1st Infantry Division on D-Day, was one of the first correspondents into Buchenwald after it was liberated in April 1945, and was on hand for the linkup of U.S. and Russian troops at the Elbe a few weeks later.

Sicily did, however, mark the end of his days parachuting into battle, as he had vowed in his July 19 story:

The rest is history now -- how paratroops scattered all over southern Sicily fought their way northwest, disorganizing all of the rear area. But this correspondent now is going back to covering the entire ground fighting front and leaving future paratroop missions to other and younger men who had better be rugged.