At least a week before three Navy officers showed up at their front door in Waterloo, Iowa, Alleta and Thomas Sullivan had a feeling something horrible had happened.

As the calendar turned to 1943, they continued to hope each day for a letter from one of their boys serving in the Pacific. The last had been dated Nov. 8, 1942. Of course, who even knew how any mail made its way across the ocean during wartime, so there could be any number of reasons for the delay.

On Jan. 5, though, came a foreboding sign. A fellow Navy mother told Alleta she had received a letter from her son that mentioned in passing, “Wasn’t it too bad about the Sullivan boys?”

A week later, Alleta and her husband received the unimaginable news: All five of their sons were officially missing in action after their ship, the USS Juneau, had been sunk near the Solomon Islands nearly two months earlier.

George, Frank, Joe, Matt and Al Sullivan had enlisted after the attack on Pearl Harbor, vowing to avenge family friend Bill Ball’s death aboard the USS Arizona. The decision marked a return to the Navy for the two eldest Sullivans, George and Frank, who had served from 1937 through May 1941.

The critical factor was their demand to be allowed to serve together, which ran contrary to Navy policy. Among the extensive coverage in the Waterloo Daily Courier the evening of Jan. 12, 1943 was a statement from a Navy personnel official in Washington obtained via long-distance telephone call: “Presence of the five Sullivans aboard the USS Juneau was at the insistence of the brothers themselves and in contradiction to the repeated recommendations of the ship’s executive officer. Serving together had been one condition of their enlistment.”

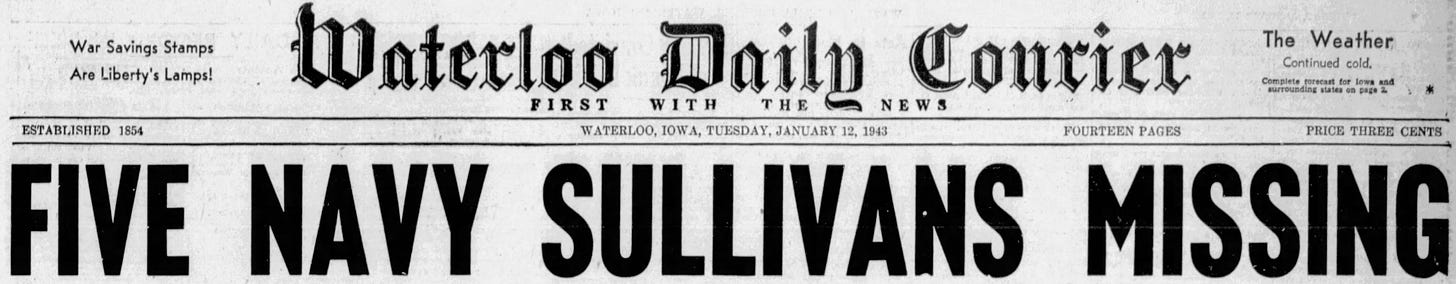

The Sullivan brothers story ran on front pages across the United States and Canada, with wire-service reporters supplying a steady stream of copy over the next few days. But the impact was deep and personally felt in Waterloo, where the Daily Courier devoted extensive coverage to the news under banner headlines.

While staff writer J.L. “Dixie” Smith’s lead story stuck mostly to the basics, providing official information and biographical details on the brothers and their father, a railroad freight conductor, a Page 3 sidebar by Kenneth Murphy delved a bit deeper into the close-knit family. Describing the brothers’ reaction to the Pearl Harbor news, Mrs. Sullivan shared this with Murphy:

“I was crying a little,” she says. “Then George said, ‘Well, I guess our minds are made up, aren’t they, fellows? And when we go in we want to go in together. And if the worst comes to the worst, why we’ll have all gone down together.’”

As the still-emerging details would show, that wasn’t precisely how things transpired. The middle brothers, Frank, Joe and Matt, apparently were killed in the massive explosion after a Japanese torpedo struck the ship near Juneau’s magazines. The other two brothers reportedly survived the initial blast, but Al drowned the following day and George a few days after that.

The Jan. 15 Daily Courier published excerpts from a letter sent to Mrs. Sullivan by a Juneau survivor who said he was on a life raft with George before he died.

“It was a sad and pathetic sight to see George looking for his brothers,” the unidentified sailor wrote, “but all to no avail.”

On the U.S. Capitol lawn in the NE corner of the area before you cross the street to the Supreme Court are 5 cherry trees and a large plaque dedicated to the Sullivan Brothers.