The story of Maj. Thomas D. Howie moved readers before they even knew his name.

On July 18, 1944, correspondents accompanying the 29th Infantry Division into Saint-Lô led their stories with a vivid illustration of the cost of battle. Wrote Hal Boyle of the Associated Press:

An ambulance in the first American column to roll into St. Lo tonight carried in state through the battered streets the body of a Virginia major killed in battle after winning dominant heights enabling other troops to breach this German stronghold.

This gallant gesture was made on personal orders of the commanding general of the major's division, as a tribute to the dead officer. The general felt the major's sacrifice had won deathless honor for his division, for his men, and for himself.

Boyle's fourth paragraph notes that the major's name cannot be released until his family is notified, then continues to describe the scene. Quoted at length is Capt. Thomas D. Neal, who had been assigned to bring the officer's body into Saint-Lô by Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt.

"The general wanted him to be among the first to enter the city," Neal said. "He died trying to win it, because if it hadn't been for his bravery and military ability we wouldn't have gotten in so quickly. It is a tribute to him and to his determination. The men feel good about it and it means a lot to them, particularly to the men of his own unit. He was a very popular officer and the men liked him a lot."

Neal and a handful of other men found the major's covered body in the field where medics were still working to treat American and German wounded who had been brought back a few hundred yards from the front. They lifted his body "reverently" onto a litter, covered him with a raincoat and blanket, placed him on a jeep, and drove slowly up a dirt road toward the column assembling for entry into Saint-Lô. There, they transferred him to an ambulance.

The medics running the ambulance had only been told of their duty moments earlier, Boyle wrote.

The little group was deeply impressed by the solemnity of this unusual and symbolic mission.

"Do you wish to see the major?" Private Christ asked. I nodded and he led me to the rear of the ambulance. The major lay in an upper stretcher and was hidden in the deep anonymity of death. A blanked shrouded him completely.

Ahead of them, the column begins to move out of the orchard and onto the road toward Saint-Lô. Military policemen gesture to keep the procession moving.

Private Christ slowly shut the ambulance door as the medics climbed in.

"He must have been some major--that major," he said. Then he climbed in, too.

The ambulance and the dead major moved down to their rendezvous in St. Lo.

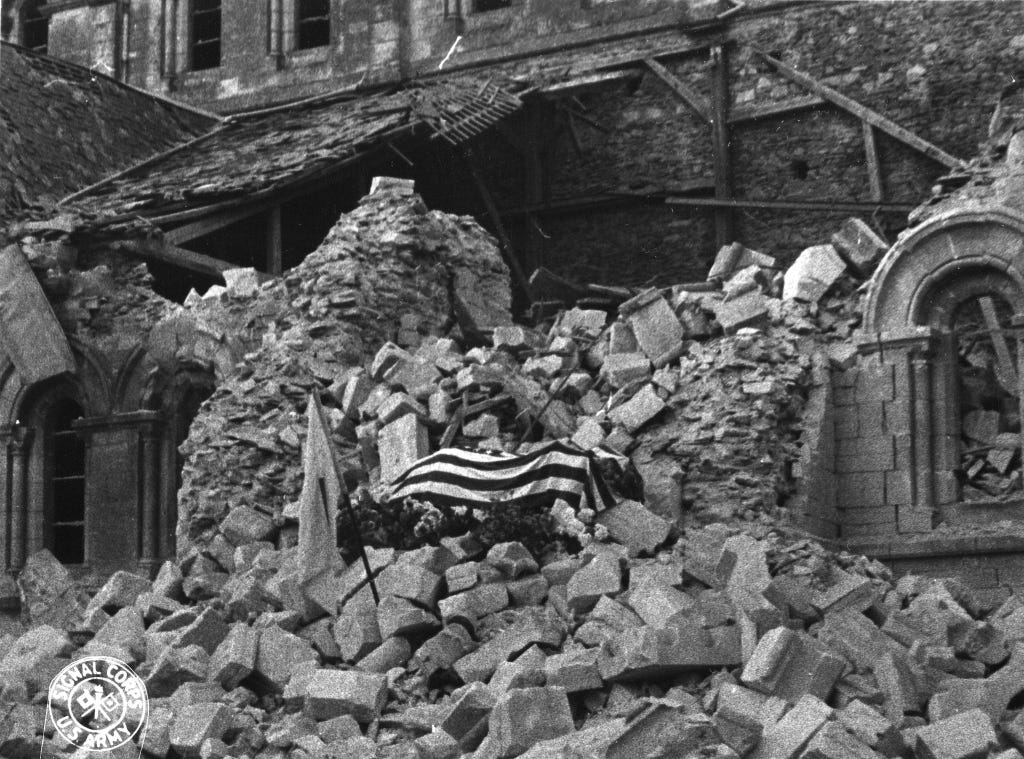

Once inside the town, Neal's party placed the major's body on the rubble of St. Croix Cathedral and covered it with an American flag, creating an impromptu shrine.

While Boyle's story on the anonymous major likely was the most widely read, given the Associated Press' vast distribution network, other correspondents were on the scene as well. Harold Denny of the New York Times mentions in his account, which is focused more on the big picture around Saint-Lô than Boyle's, that he had encountered the major before:

Only two days ago I was visiting him in his command post in a ditch, and he was talking of this town, toward which he had been leading troops.

Denny's account went on to share the backstory of what had occurred. The 2nd Battalion of the 116th Infantry Regiment, led by Maj. Sidney V. Bingham Jr., had approached Saint-Lô on July 15 but was caught in front of the rest of the Allied forces and cut off. "The enemy closed in behind Major Bingham's men and ceaselessly bombarded them," wrote Denny. "He held on."

With food and ammunition nearly gone, Bingham's group held on until 3rd Battalion, led by Howie, managed to reach them. Early on July 17, 3rd Battalion then attacked toward Saint-Lô after fighter-bombers helped clear the way, but Howie was killed by shrapnel from a German mortar in the process.

On July 19, a day after the men of the 116th brought Howie's body into town, Bingham -- promoted that day to lieutenant colonel -- spoke to Harold Denny about what had transpired getting to Saint-Lô. The story concludes with his tribute to the still-unnamed officer:

"He was a fine soldier and a good friend," Colonel Bingham said. "Everyone who knew him loved him. He took his Army service very seriously and if he had any fault it was that he was too conscientious. We'll miss him."

In a remarkable coincidence, the July 19 Baltimore Sun included a story summarizing a letter Howie had written to his father in law in Baltimore, McLellan Smith, on July 7. (Papers running these types of stories, or even printing letters verbatim, was common during the war.)

In one passage quoted in the article, the 36-year-old Howie writes:

"We're still hitting the ball at a good clip, though the caliber of our opposition is improving steadily -- more Nazis and fewer Russians, Poles, Czechs impressed into service. The Nazis are arrogant, and we aren't taking many prisoners. Except for dead and wounded friends, life in combat doesn't seem a great deal tougher than maneuvering in England or amphibious operations on the coast of England.

"I think the toughest part so far has been the mental adjustment to killing and being killed. What we saw and experienced from D to D-plus-three shocked us pretty hard, but I believe now I can endure almost anything.

"And those of us who have survived, both physically and mentally, are pretty callous. The American army in Normandy is learning to hate, a new experience for most of us."

The 29th Division saw its first combat action on D-Day, with the 116th Regiment leading the first wave onto its assigned sector of Omaha Beach. In his letter written a month and a day after that experience, Howie lauds the courage of both his men and the French civilians they have encountered since landing in Normandy.

With supply lines now stronger, he welcomes the improvement in rations available to men in the field, which the 116th has been, virtually non-stop, since hitting the beach at 6:30 a.m. on June 6. The Sun's story on his letter concludes this way:

"Since D-day and H-hour, our regiment has been in action, except for two days of heavenly rest. Had my second bath and change of clothing three days ago, within short mortar range of the Jerries -- an improvised field shower made out of wine barrels, C-ration cans with punched holes, and kitchen hot-water heater. A hot bath is the ultimate luxury."

Major Howie ended his letter with greetings to relatives, and the expressed belief that he, "an old soldier," would survive any hazards.

Some time within the next 10 days, Howie's family received the awful news.

The main headline in the July 29 edition of The News Leader in Staunton, Virginia, read: "Heroic 'Major of St. Lo' Revealed As Staunton's Own Thomas D. Howie".

Below it ran a three-column photo of Howie's body lying in state on the cathedral's stones and a follow-up story by Boyle carrying a July 23 dateline.

They passed out presidential citations today to officers and doughboys who cracked St. Lo, the eastern hinge of the German battleline, and it was a sad ceremony to many because the "Major of St. Lo" was not alive to receive his.

The "Major of St. Lo" was Thomas D. Howie of Staunton, Va., one of the best beloved battalion leaders in the American Army. He was killed July 17, the day before the city fell, after he broke through the Nazi wall to relieve another battalion of this regiment which was encircled on the outskirts.

With Howie's identity now public, Boyle sketched out a brief biography:

Howie was bald and in his middle thirties. He formerly taught English literature, coached football, and was athletic director at Staunton Military Academy. He was an athletic star himself at the Citadel, military academy in Charleston, S.C.

The wiry, muscular officer, a native of Abbeville, S.C., was popular with all ranks in the division from the lowest private to the commanding officer, Major General Charles H. Gerhardt, who personally ordered Howie's body taken into St. Lo by the combat force as a gesture honoring him and his battalion. By taking the high ground dominating the approaches to the city, his men sealed its capture.

The rest of Boyle's piece is devoted to the words shared by Howie's men. Capt. William H. Puntenney, 3rd Battalion's executive officer, said he caught Howie as he fell, bleeding from the mouth, after being hit in the back with shrapnel.

"I called a medic, but nothing could be done. He was dead in two minutes.

"Before we jumped off that morning he had told some division officers: 'See you in St. Lo.' General Gerhardt knew that if he lived he would have wanted to be one of the first in the city -- and he saw that he had his wish."

The story says four enlisted men in an adjoining foxhole were wounded by the mortar burst that killed Howie, but all insisted on staying at their posts.

When it came time to say a few words in Howie's memory, it was T/4 Clarence Garelik of the Bronx delivering this eulogy:

"Every one of us enlisted men looked up to him and admired him as a leader. But at the same time he was so kind and considerate you always felt comfortable around him -- even if you were a private and he a major."

Howie's legacy lives on more than 75 years after his death. Memorials from Staunton to the Citadel to his hometown in South Carolina to Saint-Lô itself honor his memory.

His story also is said to have been the inspiration for Capt. John Miller, the character played by Tom Hanks in "Saving Private Ryan."

The Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, which features prominently in the film, is also where Howie lies at rest.

A wonderful tribute to a courageous leader. It reminded me of the famous Ernie Pyle story, "The Death of Captain Waskow."