Tuskegee Airmen: Charles B. Hall records 99th's first victory

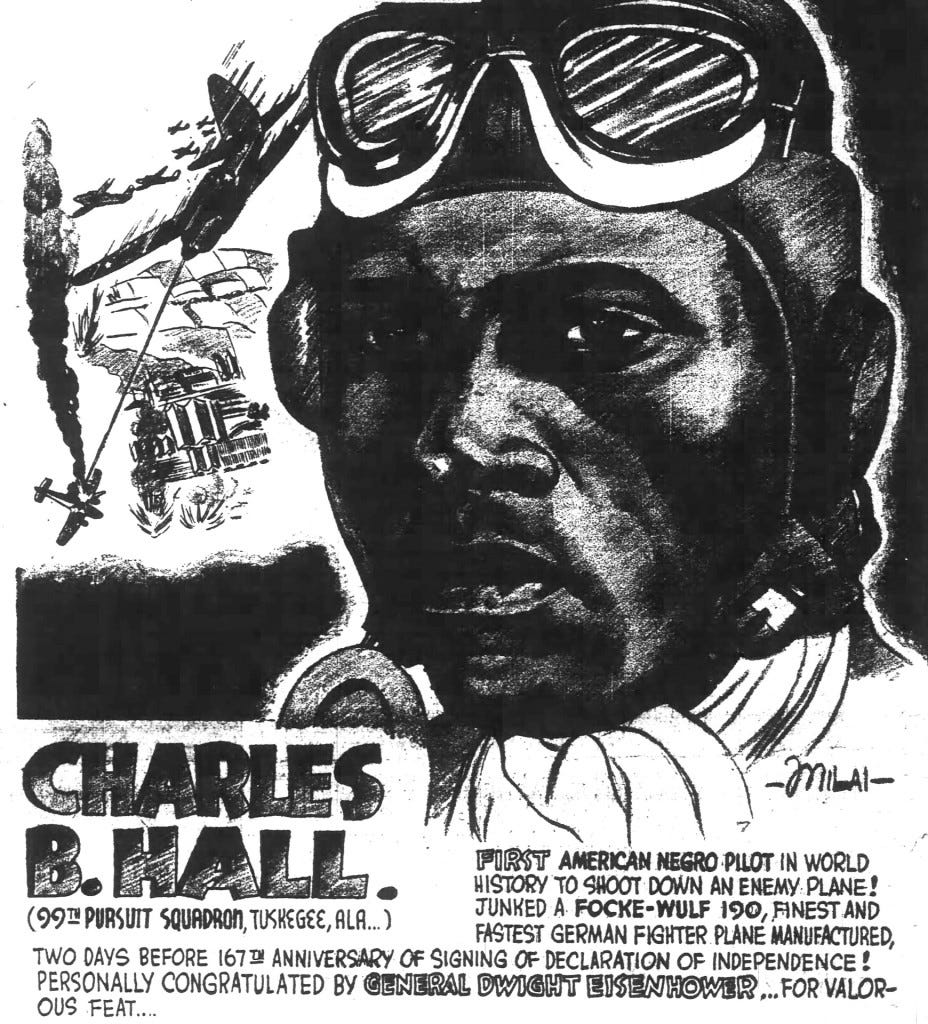

He caught the Focke-Wulf 190, Hitler's finest fighter plane, in his sights! He pressed the button ... his machine-gun roared ... and another Negro flyer had made headline history. To 22-year-old Charles B. Hall, of Brazil, Ind., first lieutenant of the now world-famed 99th Pursuit Squadron, goes the honor of being the first American Negro pilot of the United States Army Air Force to paint a swastika on his ship.

War correspondent Edgar T. Rouzeau's lead in the July 10, 1943 edition of the Pittsburgh Courier rang out with pride over Hall's aerial victory eight days earlier, the first true combat highlight for a unit that already had become the darling of the Black press.

We now refer to them generally as the Tuskegee Airmen, but that term didn't come into wide use in the media until the early 1970s. At the time, the mainstream media often called them something like an "American Negro fighter squadron," as the United Press put it in a brief item recounting Hall's triumph. In newspapers serving an African American audience, however, they were often called simply the 99th, and readers were well-versed in the backstory of Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. and his men.

After training in Tuskegee, Alabama, the 99th shipped out to North Africa in the spring of 1943. Flying out of Fordjouna, Tunisia, pilots from the 99th saw their first combat action escorting bombers in Allied operations against the island of Pantelleria in early June.

All of the above was covered in detail by the Courier, the Baltimore-based Afro-American, the Chicago Defender, the New York Amsterdam News, the Atlanta Daily World, and numerous other newspapers nationwide serving the Black community. So you can imagine how significant the events of July 2, 1943 were for a segment of the U.S. population that was fighting for rights and respect in day-to-day life while also playing a critical role in the war effort.

That Friday, Hall and other pilots from the 99th took off from Tunisia in their P-40 Warhawk fighters, escorting a flight of B-25 bombers in a raid on Castelvetrano airfield in western Sicily. Hall told his story to correspondents back at the base:

"It was my eighth mission by the first time I had seen the enemy close enough to shoot at him. I saw two Focke-Wulfs following the Mitchells just after the bombs were dropped. I headed for the space between the fighters and bombers and managed to turn inside the Jerries.

"I fired a long burst and saw my tracers penetrate the second aircraft. He was turning to the left, but suddenly fell off and headed straight into the ground. I followed him down and saw him crash. He raised a big cloud of dust."

Back in Tunisia, Hall received a hero's welcome, and a long-awaited gift. The 99th had saved its last bottle of Coca Cola "for the pilot who put the first notch in his guns," as Ollie Stewart wrote in the Afro-American. "Fabulous prices have been offered for the coke and it had to be well guarded. Hall is perhaps the best liked man in his squadron; always smiling and always ready to fly."

While the prized bottle may have been the most meaningful tribute offered up to the victor, that wasn't the extent of the celebration. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and several other high-profile officers, including Gen. Carl "Tooey" Spaatz and Gen. James Doolittle, were on a tour of North African airbases that day. Eisenhower personally congratulated Hall on his feat.

Reports that day suggested the 99th might also have shot down an Me-109 and possibly damaged another German fighter. Research decades later by Dr. Daniel L. Haulman of the Air Force Historical Research Agency determined that Hall's kill was the lone victory for the 99th that day -- and indeed the only one in 1943, though the Tuskegee Airmen would rack up more than 100 confirmed victories by the end of the war.

Associated Press correspondent Noland Norgaard's story datelined July 3 noted that Hall had been enrolled at the Illinois State Teachers' College (now Eastern Illinois University) but left his studies for flight training at Tuskegee. That was about the extent of the biographical detail offered up on the hero of the day by the traditional media, but the Black press made telling Hall's story a priority over the coming weeks.

Part of that was a function of the newspapers' publication schedule. They came out weekly, on Saturdays, so they had a week of lead time to put together stories on Hall from the time he landed back in Tunisia and would continue to build from there in subsequent editions.

The Courier's July 10 issue featured a huge headline over the masthead that read "99th PILOT DOWNS NAZI PLANE" and a front page dominated by a stunning, comic book-style portrait of Hall by editorial cartoonist Sam Milai.

The Courier featured Rouzeau's main story on the cover and two more sidebars inside with July 4 datelines. Randy Dixon wrote from London about the attention Hall's exploits received in the British press, while Charles Davis wrote of a visit to Hall's small Indiana hometown:

The entire citizenry of this thriving little town is extremely proud of Charlie. They remember Charlie and his mother. They had heard of his exploits even before I arrived yesterday afternoon, and already they are talking about a memorial of some kind for him.

I missed seeing his mother, who is now living in Fort Wayne, Ind. She has been staying with a sister there since her son entered the Air Force, although she did return for a visit last summer.

That missing piece would be rectified the following week, when the Courier devoted two front-page stories and most of an inside page to Hall's family, friends and hometown -- including a picture of that house at 1034 Hendrix Ave.

Charles Davis was back on the scene, reporting that "whites and Negroes alike are happy to have 'had a hand' in raising" Hall. "We've got a new hero," they told him, the son of Anna and Frank Hall. Davis told his story:

Lt. Charles Hall's Brazil is a sleepy little town nestled in the hills of Southern Indiana. The family home still stands at 1034 East Hendrix street a little worn with age. The father, Frank Hall, died December 17, 1940, and Mrs. Anna Hall, the mother, moved to Fort Wayne, Ind., where she works in a war plant making ammunition. She lives with her daughter, Mrs. Victoria Littlejohn, there.

As a boy he did the usual things a youngster in a small town does, odd jobs here and there after school. He attended the Brazil high school and made both the football and track teams. His father was greatly interested in Charlie and whatever Charlie said he was going to do, the father would repeat and encourage it.

From the beginning they all knew he would make good in the Air Force. His aunt, Mrs. F.H. Moore who lives at 503 North Vandalia street, Brazil, said she has had a feeling all along that Charles would do something like this, something they could all be proud of.

Hall wasn't done making them proud yet. In January 1944, the 99th was on the Italian mainland, supporting operations at the Anzio beachhead, when it was called into action to repel German fighters over a two-day span. Ten different pilots recorded victories on January 27, and the squadron claimed three more kills the following day -- two of them by Capt. Charles B. Hall. Those victories earned Hall the Distinguished Flying Cross, making him the first Black pilot so honored.

Hall came home later in 1944 and embarked on a three and a half month tour to drum up war bond sales.

"We spoke to all sizes and kinds of groups," Hall told the Oklahoman's Sunday magazine in 1960, "and I was never as scared in combat as I was facing those groups."

He then returned to Tuskegee to serve as an instructor before leaving the Army Air Forces as a major in 1946.

Hall eventually settled in Oklahoma City in 1948, initially working at a drugstore before going to work at Tinker Air Force Base in 1949. He worked at the base through 1967 before moving on to the Federal Aviation Administration offices in Oklahoma City.

Hall died on November 22, 1971, just 51 years old. His passing received little public notice at the time, the Daily Oklahoman running a brief death notice on its obituary page.

Over time, as the story of the Tuskegee Airmen became more prominent in coverage and commemoration of World War II history, Hall's exploits would reach a wider audience.

In 2002, the Tinker Heritage Airpark was renamed the Maj. Charles B. Hall Memorial Airpark. Five years later, a life-size bronze statue of Hall, designated to represent the contributions of all the Tuskegee Airmen, went on display there.

In 2015, Hall's daughters Kelli Jones and Sherri Harris spoke to the Oklahoman during a visit to the memorial.

“They weren’t trying to make history,” Jones said. “They wanted to serve their country just like every other American.”